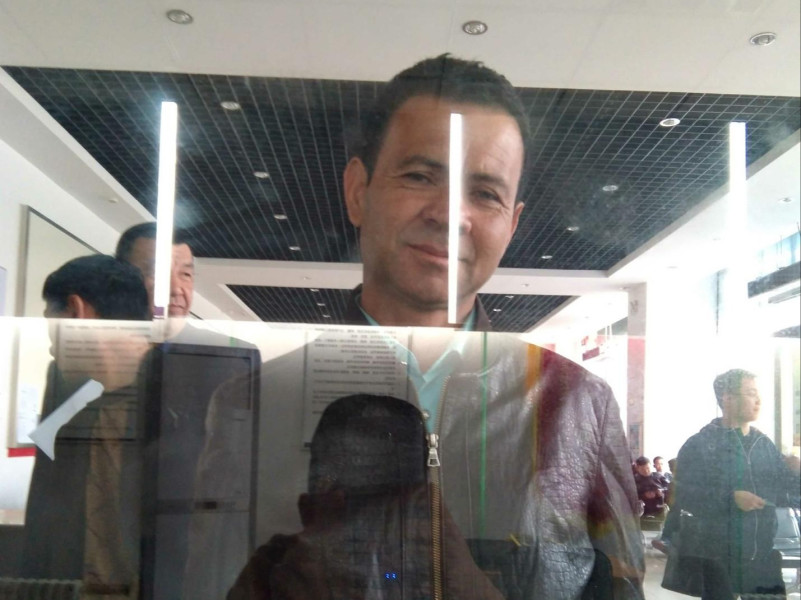

At a checkpoint at the exit of the high-speed rail station in Turpan, an ancient oasis city on the edge of the Taklamakan Desert in Northwest China, I observed how Uyghur people were directed through two long lines to have their IDs checked while Han-passing people were permitted to go through without any check at all. An Uyghur officer was staring at us, trying to identify ethnicity by the shapes of noses and eyes to determine who must have their faces scanned. Speaking Uyghur, I asked the Uyghur women around me which line a foreigner should go through. They directed me to go with them.

When it was my turn, I explained in Uyghur to the young Uyghur “police assistant”—a term translated from Chinese, which refers to deputized citizens who work as the lowest level police—that I was not Han or Uyghur. He said we needed to go into the police station across the square to register. As we walked toward the station he pointedly asked me if I could also speak Chinese. He seemed to suggest that I do so when we entered the station. As we walked in, I immediately understood why. Han officers—state-authorized representatives of China’s non-Muslim Han majority—were observing the work of the many Uyghur “police assistants” in the station. The Han settler-led mass internment of hundreds of thousands of Uyghurs was reaching its peak in 2018, before the camps turned into factories and formal detention centers or, in some cases, closed. If I spoke Uyghur, it would have likely raised suspicion on my purpose in the region and my politics. I explained in Chinese that I was just visiting Turpan for the afternoon. An Uyghur officer scanned my face on my passport photo and then matched it to a scan of my face using a mobile app. She explained that this scan was for my protection while I was in Turpan. It was just a normal part of life here.

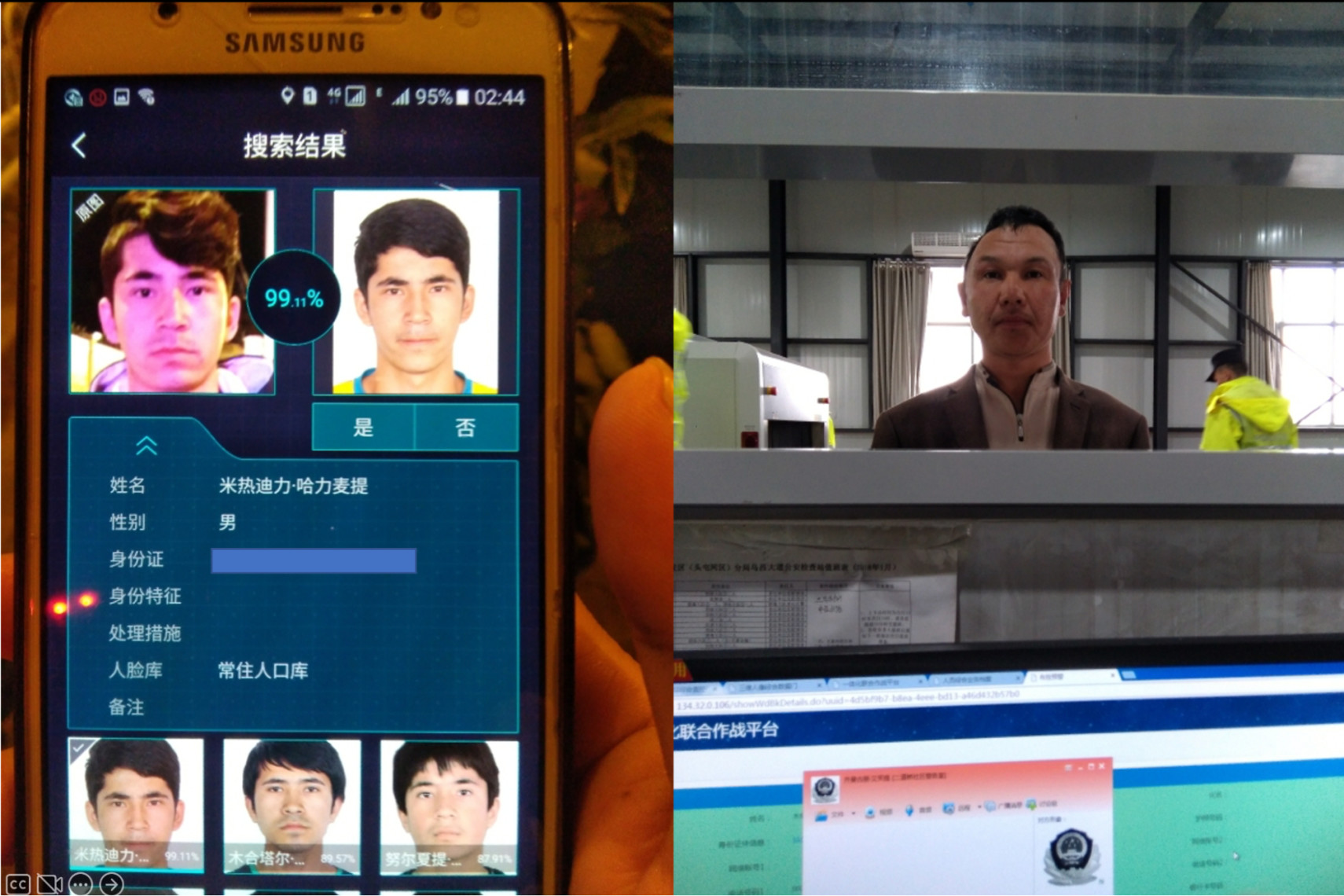

While I was being processed in the station a young Uyghur man was escorted in. A police assistant had his hand on his shoulder. He stuttered a bit at the questions the officer peppered at him. Where was he from, where was he going? His face was pale. The officer accompanying him said his ID had beeped when he went through the checkpoint. My second face scan of the day was complete, so I could not stay and hear what they were going to do with him.

--

As an ethnographer who has studied the region for nearly a decade, beginning in 2010, the density of checkpoints I saw in 2018 shocked me. A matrix of checkpoints and over 7,000 surveillance hubs had turned every city and town I visited into a maze of digital ethno-racial profiling. During the 24 months of fieldwork I spent in the region several years before, ID and phone checks were relatively rare. In 2018, they had become standard elements of daily life. Muslims I interviewed told me that starting in 2017—the beginning of the mass internment campaign—their IDs and faces were scanned as often as 10 times per day. The checkpoints were at nearly every jurisdictional boundary: the entrance of shopping malls, banks, hospitals, schools, walled residential areas, and city boundaries. In many cases the checkpoints were only for Uyghurs. Non-Muslim Han Chinese walked through them following “green lanes,” their heads held high, not even looking at the police contractors who were waving them through. In internal police files, Muslims being detained appear to give occasional side-long glances that are hard to read.

One of the primary groups responsible for carrying out the internment evaluations of the predictive policing system, as well as constructing and refining its foundational dataset, were the tens of thousands of recently deputized "police assistants." Over my time there in 2018, I witnessed them reprimanding elderly Uyghurs for failing to produce their identification. They were also in charge of random checks at the sides of the road that only targeted Uyghur young men and women and cars driven by Uyghurs. Throughout my time in the Uyghur districts of Ürümchi, Turpan, and Kashgar, I did not once see a Han person be asked to show their ID at spot checks. In hundreds of thousands of internal police documents I examined for The Intercept, it is clear that “enemy intelligence” in the parlance of the security workers refers nearly exclusively to data gained from Muslims. Around 80 percent of the data I reviewed out of 52 gigabytes of internal police reports targeted Muslim minorities.

At some checkpoints, officers asked Uyghur young people to give them the passwords to unlock their smartphones. The officers then looked at the spyware app Clean Net Guard, built by state contractor Landasoft, a company that describes itself as a Chinese version of Palantir, using open-source software from the U.S.-based company Oracle. This app automatically scans smartphones registered to Uyghurs, searching through WeChat, Weibo, Douyin, and other apps looking for thousands of flagged images and text associated with so-called extremist groups, Islam, and Uyghur political history.

In some cases, the security workers plugged the phones into digital forensics tools built by companies such as the Chinese digital forensics state contractor Meiya Pico. These tools, referred to in Chinese as “counter-terrorism swords,” ran on Meiya Pico software that mimicked the systems built by the Israeli company Cellebrite, for whom they had built compatible hardware. Cellebrite, one of the world’s largest retailers of digital forensics tools, is one of the first companies to mass-produce dataveillance tools. They are now used by “6,700 public safety agencies and private sector enterprises in over 140 countries” around the world, including by Indian state security in Kashmir. Meiya Pico systems or law enforcement training services are used in 29 different countries as of 2019.

In China, Meiya Pico dominates this multi-billion dollar industry. The Meiya Pico version of Cellebrite tools in Northwest China scans through the digital histories embedded on devices looking for partial matches for as many as 70,000 different markers of so-called “extremist” Islamic or terrorist tendencies. For instance, it looks for images of men with beards or women wearing hijabs, or for an expansive list of WeChat study groups. It can detect past installations of Virtual Private Network (VPN) software and encrypted social media apps such as WhatsApp. It may sift through digital banking history as well as patterns in movement such as frequent visits to mosques. Ultimately, it collates these datastreams to present a reading of Uyghur citizens according to a scoring system that defines trustworthiness and untrustworthiness.

An internal state document from late 2017, a few months before my visit, stated that the use of an illegal file-sharing app had been detected in the digital histories of as many as 1.8 million Uyghurs in the region. Based on my interviews with former detainees and camp workers it is clear that many of those who used this and other banned apps were deemed to be potential terrorists and were accordingly sent to the internment camps.

--

My observations of Northwest China illustrate the way that contemporary colonial projects tend toward the “operational enclosure,” which describes a digitally-mediated social hierarchy in which the movement and behaviour of certain racialized populations are made automatically detectable and thus controllable, while privileged settler populations are permitted to move around in a relatively frictionless way—for instance, doors are opened automatically for them by security workers who profile them, or by camera systems that identify them as non-Muslim. Coined by communications scholars Mark Andrejevic and Zala Volcic, this form of enclosure is being adapted by government agencies and corporations across the Global South to slot marginalized populations into the operative logics of actionable intelligence. For privileged settlers, a seamless digitally integrated society brings them pride in the advancement of their country’s capabilities along with consumer convenience. For Muslims, on the other hand, the operational enclosure provokes intense fear.

In Northwest China, advanced dataveillance technology is key in producing an efficient settler colonial state that can classify and segment its inhabitants. Two interrelated phenomena are at play here, one regarding the technology itself and the other about how it molds social reality. First, the technology is a black box—security workers do not really understand how it works beyond the reductive readouts they see on their screen: 99.11 percent match. Orange tag. Potentially “untrustworthy.”

Second, in practice these simplistic characterizations and predictions come to be seen as truth. The technology is viewed as an unquestioned authoritative good, since it is perceived as scientific and state-of-the-art intelligence. The predictions made become legally enforced truths.

Together, these two elements, the digital black box and the legal and social discourse of technological intelligence, are producing one of the first mass experiments in the colonial operational enclosure.

--

In situating contemporary Chinese coloniality within global history and the global economy, I take inspiration from Ivan Franceschini and Nicholas Loubere’s framing of “global China as method.” Their approach attempts to disrupt Cold War binaries that frame contemporary China as a discrete entity defined by its opposition to the Western “free world” and therefore disconnected from the political logics, militarism, and economies of North America and Europe. Thinking in this manner is helpful for understanding China’s current status as a subcolonial power—a former semi-colony of European, North American and Japanese imperialisms that is now claiming its own colonial possession and doing so by adapting Global North militarism and colonial strategy.

A subcolonial or subimperial state is defined by the learned behaviours taken from its former colonizer. Rather than framing such a state as neo-colonial, a frame that tends to be somewhat dehistoricized and focused on financial systems, a subcolonial or subimperial frame highlights how it functions by dominating the school systems, legal systems, religious institutions, and financial institutions. It also emphasizes that China’s position is similar to that of Israel and India—where past wounds of genocide and colonialism motivate imperialist ambitions, especially related to ethno-nationalist economic development. This logic is used to justify China’s internal colonization of others as both manifest destiny and beneficent paternalism to the colonized on China’s Inner Asian frontiers: Tibet, Xinjiang, and Mongolia.

As Uyghur scholars such as the imprisoned economist Ilham Tohti have shown, the land and labor of the Uyghurs are highly desired in the Chinese export-oriented economy. Over the past three decades, Han settlement of Uyghur and Kazakh ancestral lands have resulted in settler-run industrial farms that account for nearly 20 percent of the world’s supply of cotton. Furthermore, Uyghur lands are now the source of nearly 20 percent of China’s oil and natural gas. As I argue in Terror Capitalism, Uyghurs have been placed in a state of exception as a population of terrorists-in-waiting, undeserving of autonomy granted to the non-Muslim majority. Instead they are to be removed from their land, put to work in factories, and managed through automation-assisted policing.

Security studies in the Global North have been dominated by analysis of the U.S. Global War on Terror and the way it may mask ongoing imperialisms of the Global North. At the same time, security studies in the United States in particular has shifted focus to the supposed threat posed by a global China—producing the New Cold War rhetoric. A more nuanced view of contemporary colonialisms attempts to show how these different forms of imperialism are entangled with each other and how they need to be opposed simultaneously.

Chinese policing strategies make it clear that Israeli, American, British and Russian approaches to data-driven, preventative policing are viewed as models that should be emulated and perfected at scale in Chinese contexts, as we see in the case of the dataveillance offerings of Meiya Pico. In other domains, such as voice and facial recognition, Chinese security contractors now compete with and at times surpass their Israeli and American counterparts in terms of technological capacity. This is troubling, not because China appears to be “winning” in building technologies of control, but because these harmful technologies are proliferating at an exponential pace.

Though these systems appear all-encompassing, they still need to be implemented and maintained. As much as they are designed to classify and control human behavior, some parts of life remain outside their grasp. It is here that Uyghurs continue to find ways to live and resist.

--

But how exactly do these enclosures fail to fully control people? Sometimes the limits of the enclosure system were self-evident, as Uyghur fear and rage wells up to push against it. For instance, at a security checkpoint, I witnessed a distressing scene involving a Uyghur woman and a Han security officer. The woman, with tears streaming down her face, yelled at the officer in Chinese, demanding to know how many family members he had left in his family. The question probed the racialized reality of mass internment and seemed to catch the non-Muslim police officer off-guard. He stuttered in response, first in Uyghur, then in Chinese, repeatedly saying, "No! No!" For a few minutes the woman created a spectacle by simply loudly asking a question that probed the scale of mass internment. While this may have resulted in her internment, in the moment, it demonstrated that Uyghur citizens had not been fully stripped of their agency.

Similarly, in my interviews with former detainees such as Vera Zhou—a Chinese Muslim college student detained in 2017—I found that even in tightly surveilled camp cells, she and other detainees were able to collectively mourn and document the injustice of their criminalization. Ironically, they did this by collectively writing weekly confessions or “thought reports,” which the camp wardens demanded from them individually. As Mandarin speakers like Vera helped older detainees who could not write Chinese, they learned that none of them were really guilty of a crime and that they were detained because of their religious and ethnic identities.

According to my interviews with family members of the detainees, a culture of hidden solidarity developed outside of the internment camps. They relied on one another for emotional support as they coped with the sentencing of their loved ones. To avoid detection, they used coded language and sought out locations without cameras or electronic devices to discuss the traumatic events they had witnessed. Despite the intense pressure from the Chinese government to keep silent, these family members found a way to connect and share their experiences with each other, demonstrating resilience in the face of adversity.

Colonial operational enclosures also affect members of the targeted communities who are coerced into or unknowingly enlist in building and maintaining them. The account of one of the former “police assistants,” a Kazakh man named Baimurat, speaks to the way surveillance and state violence become normalized and banal.

Baimurat, a former police assistant in Northwest China, initially took the job in 2016 as a means of supporting his family and avoiding internment. In an interview with the exiled Chinese-Kazakh community in Kazakhstan after his escape, he shared that he had expected to work as a simple supermarket security guard, unaware that he would be profiling Muslims and transporting detainees to the camps.

However, the gravity of his job duties became apparent to him during one particular assignment, when he was tasked with transporting nearly 600 detainees from a jail facility to a camp. Baimurat recounted that he had to shackle their hands and feet and place black hoods over their heads. "We had so many manacles," he whispered to the other men in the room. "I saw very young women, very old women and men with white beards among the detainees." He noted that all of the detainees, save for one or two, were Muslim.

Baimurat was deeply disturbed by the treatment of the detainees, particularly an old woman with a leg injury who was dragged onto the bus by police contractors. "I will never forget her screams," he said, placing his hand over his heart. "When I witnessed this, I felt terribly bad. I regretted being a police [assistant] with every fiber of my being. I was crying on the inside." As Baimurat recounted his story, the other men in the room, many of whom had loved ones in the camps, listened intently and shook their heads, their knees touching.

Stories like Baimurat’s show that members of the targeted community themselves have not only been forced to contribute to the building and maintenance of these systems, but also how they live on despite them. The colonial collaborator—someone who is always ambiguously situated between the oppressor and the oppressed—can be a subject of contestation. The emotional moment Baimurat described reveals his complicity and his struggle to grapple with this. It also shows how a community mutually recognizes and processes the complications and challenges of their entanglement with this operational enclosure and marginalization.

--

From Palestine to Kashmir to Xinjiang, a suite of strategies and technologies born out of the U.S. Global War on Terror are being utilized to turn colonized populations into objects of control within operational enclosures. Weapons and tactics originally developed by the imperial powers of the Global North have been repurposed for Israel's violent expansion into Palestinian territories and are now being used to further new sequences of settler colonialism throughout the Global South. Acknowledging this colonial trajectory is useful in comprehending the vast magnitude and intricate mechanisms of the imperial endeavor of policing. It demonstrates how European and North American empires have shaped practices elsewhere, and as Samar Al-Bulushi, Sahana Ghosh and Inderpal Grewal put it, “not in isolation, not without tension, and not without links to other empires.” Describing this complexity deconstructs empire as a singular object that can be diametrically opposed. While ostensibly anticolonial, such a frame ironically positions the European and American colonizer as the “normative interlocutor” from which the Global South is allotted only the role of “proxy” or “adversary” relative to the presumed imperial core, as Ella Shohat notes.

Historically anti-colonial movements have drawn from each other. This is why The Wretched of the Earth and its filmic depiction The Battle of Algiers became important touchstones for the Black Panthers. In the inverse trajectory, this is why Spike Lee’s filmic depiction of Malcolm X and a translation of Toni Morrison’s Beloved affected a generation of Uyghur youth in the 2000s. In the current moment when technology-enabled authoritarian governance is beginning to dominate emergent colonial systems across the Global South, targeted communities draw on what Deniz Yonucu refers to as a “cultural archive of oppression and resistance” as a resource to live—with and against ongoing repression.

As colonial technologies move further around the globe, the living repertoire of ongoing resistance shows the cracks in the system and strategies for how targeted communities can maintain mutual support. Practices that draw on communal life before, during, and often long after the imposition of a colonial state should be recognized and uplifted as practices that sustain life and freedom in the face of deepening surveillance states and that gesture towards potential better worlds, even as it appears that the world is being unmade.