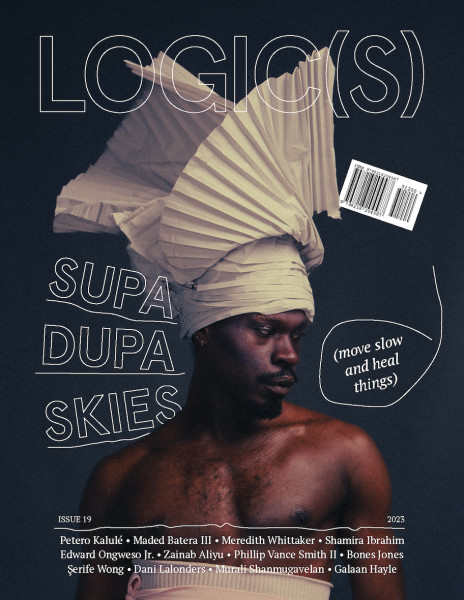

The theme of this issue, supa dupa skies (move slow and heal things), is in part an homage to Missy “Misdemeanor” Elliott’s 1997 debut studio album. Her transgression of hip hop’s dominant archetypes—Madonna or the Whore qua almost asexual hip hop purist or video vixen—cracked the sonic uniformity stagnating on the radio. Unapologetic blackly, 1 Missy denied entrenched dualities from gender cum sexual dimorphism, booty call vs. commitment or East Coast lyricism vs. West Coast gangsta rap. In the Hype Williams directed video for “The Rain (Supa Dupa Fly),” she dons a metallic space suit transformed into a delightfully outrageous visual confidently leveraging fatness via a fisheye lens. With the goal of detonating the bleak uniformity of tech journalism, supa dupa skies riffs on Missy’s audacity—her declaration that she was more than Curtis Mayfield’s superfly, she was supa dupa fly. This issue heralds the dawn of a new era for Logic(s) and we plan to do something very different than counting up falling sky Chicken Little style. We switching out the stultifying dread and doomsday hand-wringing for Black joy and rhythmic plurinational freedom dreaming. We storytelling outchea.

In a 2022 essay from History and Theory, “Predictions without Futures,” Sun-ha Hong describes how allegedly “impersonal” and “exempt from disillusionment” beliefs in technological change saturate the present horizon of historical futures. Hong reviews how the insistence on AI as the “skeleton key” to all social problems is the precise mechanism by which technofutures enact a hegemony of enclosure and sameness. Drawing on religious studies, he emphasizes how these actuarial logics constitute cosmograms—“universalizing models that govern how facts and values relate to each other, providing a common and normative point of reference.” The titans at the center of the highly concentrated tech industry relentlessly broadcast hyperbolic proclamations that characterize their products as immanent and imminently apocalyptic sentient robots. And while aiming for pushback, critics too often move in sync with these corporate proclamations (albeit synchronization characterized by vastly asymmetrical access to resources), debunking the “AI hype” while at the same time elevating and disseminating it. Ultimately, Hong’s essay brings us face to face with a pressing question: does contrasting white tech bros’ speculative fiction marketed as scientific truth with detailed documentation of racialized harms that corporate tech is enacting in the present, do anything to fundamentally challenge the modernist symbolic order?

We think about this question alongside “What Will Be the Cure?,” a conversation in Offshoot Journal between Bedour Alagraa and Sylvia Wynter. In this conversation, Wynter says that in order to forgo the cheap and easy radicalism of the Marxist project in Guyana and its quest to simply organize the state differently, we must begin to tell different origin stories of who we are as Black people and as Africans. “Language is the way that we will carry ourselves out of these problems we have—that is what is important now to remember about Black studies during those early years, that it was one part of a bigger project of developing a transformation of knowledge and therefore the transformation of the whole of society, by using a different language to address these intellectual concerns.” If we take Wynter’s prompt to “reimagine the world anew” seriously, what other stories can we tell about ourselves?

Shamira Ibrahim’s “Haitian Rhythms Under Scrutiny” asks that we relocate Guantanamo Bay to 1994 when Haitian immigrants—fleeing the conditions produced by post-independence colonial contracts with France and US imperialism—were indefinitely detained and their blood regularly surveilled for HIV/AIDS. How do Blackness and Haitianness destabilize dominant conceptions of mestizos at the border? What Haitian counter-cosmologies not only debunk the so-called “4-H disease” (Haitians, hemophiliacs, heroin addicts and homosexuals that were reported by the press as the primary vectors of HIV/AIDS) but shift how we racially narrate movement across borders into social classification i.e. maroon, criminal, or immigrant? Besides facial recognition technology applied at the US/Mexico border, when else do we fail to recognize dark skin? Can embracing Haitian life, movement, and vodou epistemologies re-situate imperial catastrophe away from origin stories that encode Haiti and Africa as an affliction in and of itself?

And what to make of recognition and solidarity? As we’ve worked to lay the foundation for the new era of Logic(s), we’ve thought a lot about our investments in international coverage and what Black-Asian solidarity actually look like in practice. It’s challenging because, as Murali Shanmugavelan mentions, “not every person of color needs to be an ally of social solidarity, especially coming from South Asia [where so many are caste oppressors].” At the same time, in our conversation with Shanmugavelan, he emphasizes how painful it is for caste violence to be encoded within the Western lexicon, circulating unmarked of its original context. For example, “pariah” became a violent caste epithet hurled against Dalits in southern India who ceremonially played the drums—parai in Tamil—but in the West it’s deployed as a generic signifier for social outcast.

Three plus years into a pandemic, with preexisting social suffering intensified, everything is coated with a Malthusian air that leaves so many raw and wounded. Solidarity requires suturing these open wounds and attending to each other’s pain without what Frank Wilderson describes as “the ruse of analogy” (meaning sincere intimacy requires us to differentiate between anti-Blackness and caste violence). We must refuse subsuming differences into “convenient” categories. Like Joshua Bennett says, “I know/the respectable man enjoys a dark/body best when it comes with a good/cry thrown in.” Counter to Facebook’s mantra, we must move slow and heal things, notice how the urgent tempo of crisis and catastrophe produces a linear time in which the Black body is nothing but a justifiable tool to reach for, how easily Black becomes a metonym for dead yet laboring. How can we share experiences of humiliation and punishment but also recognize how our plights are distinct, with uniquely different ramifications?

Slowing down makes it possible to undo “the inevitable.” We can slow down enough to notice the endogamous transmission of specific modes of power, place, and possibility. Notice the ongoingness of pre-transatlantic slave trades and colonial intermediation. Speak in different registers, in the way Galaan Hayle describes his visit to the Warraa Ayyaanaa—an Oromo medicine woman—whose cure requires opening up an intergenerational conversation. We can notice that underneath the Brahminical story of success lie Dalit and Adivasi farmers who are collective custodians of genetic seed banks and Kashmiris resisting Indian occupation. As per Murali, we can differentiate between those to whom we ought to extend solidarity and those who are handmaidens of empire and white supremacy. Instead of the rhythmic doom evangelized by corporate tech and many of its critics, Şerife Wong explores lineage, relation, and care through her writing and illustrations about Tehzip, an Islamic book illumination practice that, unlike DALL-E (a proprietary generative token predictor owned by OpenAI), attends deeply to history and memory. And Romello Goodman asks us, can coding honor the dead? Can it be prepared like a warm meal for someone you love instead of being thoughtlessly A/B tested from above without warning?

We spend a lot of time “talking about Kevin,” or dissecting the cold, sociopathic affect of white supremacy because its school shooter ethos so profoundly shapes the development of technology and the working conditions concealed by the sleek, minimalist design of our personal devices. We can rest assured that while using an iPhone, we’ll never have to confront the children in Congolese coltan mines or the Amazon distribution centers enclosing the “ongoingness of slavery.”2 Meredith Whittaker directs us to think more deeply about these metal enclosures where workers pick packages per second, echoing plantation logics where enslaved Black people’s rates of cotton picked per second were continuously documented in account books. Whittaker’s“Origin Stories: Plantations, Computers, and Industrial Control” examines Charles Babbage’s calculating engines which were conceived from inception as a mechanism to ensure segmented control of workers’ bodies and time in service of the anxious capitalist class during the British Industrial Revolution. These engines templated modern computing and their methods for decreasing negotiating power of formerly agrarian white workers are closely linked to the “Big Data” practices of plantation managers in the colonies. Screening this history from the revolts of Black enslaved people—and engaging substantively with Black studies—Meredith destabilizes the dominant assumptions of (white) labor scholarship and makes some space for us to focus on Black strategies of escape, “quiet quitting,” and autonomy.

Can we sometimes wait a moment before mobilizing a critique of white supremacy, in order to reconsider what we want instead—after X system is dismantled, what are alternative models of governance? What constitutes a good life? There’s a way the urgency-induced dread forfeits the space to deliberate and reclaim different modes of time. Within Oromo cosmologies, time is conceived as a series of rounds, not unlike the Bakongo 3 cosmogram reverberating in the African American spiritual traditions cultivated during slavery. Galaan Hayle describes how the village’s earthen houses, with a central pillar, spatially/temporally/relationally organize social life and are the fundamental basis through which the cosmology, meaning-making system, and rhythm of everyday life is organized. What can gender affirming and caste annihilating Black geography look like? Amazon’s internet of things—dead babies, all eyes—has a vision for how “domestic” life ought to be reordered in service of capital. What alternate models are Dalit weavers, Filipino farmers, Oromos in the countryside, Black trans artists, custodians of? Let’s think with them in order to “reimagine the world anew!”

Computer science warns us of the “black box,” where transparency is technically circumscribed, particularly in convolutional neural networks where engineers are unable to precisely identify why some given input produces some given output within the layers of probabilistically generating algorithms. The black box is a mystery, definitionally beyond our comprehension, in which the anxieties about the algorithms rarely extend to concern for the data annotators in the Global South whose labor makes machine processing of “data” possible. Notice how this notion of a black box echoes the alternating fear and anthropological scrutiny of the “dark continent” a century earlier. AI evangelists’ singular drive to reproduce “intelligence” within a bodiless jar requires labor from the swarm of unintelligible/unintelligent dark continent bodies. The synthetic brain in a jar must consume massive amounts of “content” (aka our decentralized labor) distributed through submarine cables into data centers and encoded into binary bits before being translated onto the user interface of a now visually uniform social media or website.

In a Manichaean dichotomy, the white shrines of Apple stores and their geniuses are pseudo-saviors of apolitically coded consumption and technical troubleshooting, while Black folks in Africa “moderate content,” (read: do underpaid sanitation for an internet producing the worst things imaginable, “as if not just inevitable but impossible it could be otherwise” as I riff in a poem “no text zone” for this issue). But what if instead of screening all this from the neurologically traumatized de facto internet sanitation department in Nairobi and similar capital cities, we began from the village’s earthen houses, where Black indigenous Africans—who still exist despite the best efforts of Western-trained, postcolonial elites to claim indigeneity was a colonial invention 4— have otherwise sacred knowledge traditions? What if we didn’t turn to Heidegger, not even for a moment, and his blood and soil commitments to purify the Völkisch body or his reinstantiation within post-Arab Spring content moderation discourse and its demands to better police (and purify) the internet for the Global South? Which, within these very logics, doesn’t have the capacity to embrace Zuckerberg’s democratic values and well-intentioned vision for networked friendship, 5 presumably because the “rest of world” isn’t as Intelligent™.

Petals’ series of poems from their forthcoming book, & glee & bless, provokes us to continue rethinking the Human and the sonic possibilities of poetry on the page. Their words offer an opportunity for capacious Black gathering that resonates alongside Sarah Jane Cervenak’s book, Black Gathering: Art, Ecology, Ungiven Life. If the black box is an object echoing the previous century when Black folks on the dark continent were deemed fungible objects, this issue is a celebration of our collective subjectivity. Like oppression, emancipation is reproduced, undermined, extended or shortened in everyday practices. We can dance, we can tell other stories and shape our time, name land that’s unceded and make space for celebrating queer and trans kinship. “Let’s play with Black indigenous futurity” is what I said to Bones as he began envisioning the fashion centerfold. Moving beyond the Sun Ra visual lexicon of Black futures and the sleek minimalism structuring computer hardware (and user-funded nodes extending corporate and state spatial surveillance, lest we forget “influencers” are walking security cameras). As the Black American proverb goes, “Bones had time,” riffing on quinceañeras, Yoruba designs, and the Jetsons, he spent hours and hours crafting beautifully layered couture. Rather than flying cars, we flight across borders, plantations and gender binaries—our fashion editorial features Blackness flying through these supa dupa skies and rewriting the grammar of tech journalism.

America got almost two million people in a box right now. The call for abolition remains salient as technologies are being deployed to facilitate carceral expansion. Phillip Smith writes from prison about the electronic mail system and how correctional facilities have contracted out telecommunications services to private corporations. This transition precludes any public comment by “apolitically” shifting to vendor procurement; expanding police intelligence is transposed as a technical solution to the institutional problem of incarcerated people’s contact with the outside world. Meanwhile, the proprietary software deployed by these companies has extended the kinds of social control and surveillance imprisoned people been subjected to, to anyone they keep in contact with, producing a geospatial timestamped archive of communication networks.

Veena Dubal’s recently published essay, “The House Always Wins: The Algorithmic Gamblification of Work,” in the Law and Political Economy (LPE) Project, is a clear-eyed, incisive analysis of how companies like Uber deliberately restrict the capacity for drivers to receive a fair wage on top of being deprived of labor protections as a so-called “gig worker”—despite their functioning in practice as a full-time employee. In this issue, Agnee Ghosh takes us to Kolkata and Bangalore with a critical caste lens where we can hear firsthand from drivers whose dreams of transcending their lot in life are being algorithmically dashed. Meanwhile, Maded Batara, the spokesperson of Junk SIM Registration Network in the Philippines, emphasizes the long-historied and very much alive anti-fascist movement composed of trade unions, farmers, fishermen and technologists. As demonstrated by their staunch resistance to the SIM registration law passed by new president Bongbong Marcos, digital social control is not inevitable. Neither is solidifying alienated and individualist notions of privacy. Maded roots our understanding of privacy locally, for example, with the closely packed houses in a Manila neighborhood where coming and going into other people’s houses is the norm because what’s at stake are our people, our houses, our interdependent, connected privacies.

Zainab Aliyu’s autoethnographic meditation on the Yoruba memory “hardware,” passed down through her grandmother, loosens the fixity prescribed by computational logics and software architecture. And Dani Lalonders gathers us up in a queer of color dating video game and visual novel which them and their friends made at the beginning of the pandemic, specifically for capaciously gendered twenty-somethings socially isolated during lockdown. Darren Byler narrates how Uyghurs and other colonized populations in Northwest China push up against the limits of surveillance hubs and colonial enclosures. Byler describes how some detainees use code words and private spaces to evade police while others act as collaborators in their jobs as police assistants. And Ed Ongweso’s debut science fiction story “The Circle” takes us into the distant future where a sentient, artificial fungus is a threat, and so too are the scientists who encounter it.

So you see there are so many stories to be told—let this be a thousand invitations.

So grateful to the Logic Magazine founders, whose six years building up this passion project made birthing Logic(s) possible. All too often in this critical tech space, short-term funding and university politics result in new spaces and publications dying or being so constrained by conditional funding mechanisms and the academic job market that they can’t encode “the real” into the public script. White people publicly handing over their institution and its infrastructure to a Black, queer femme deploying Oromo methodologies and committed to international solidarity matters. We got some money now—courtesy of a multi-year grant from the Ford Foundation and MacArthur alongside a gift from Omidyar— and this is allowing us to put people on across the world, paying people above market rate for commissions and backend support like fact checking and copy editing. Shout out to the administrative team at Incite who have ensured that anyone, anywhere, regardless of citizenship status, or being “banked,” gets paid as fast as possible. We have the privilege of sharing all the sexy new things with the public, but the less visible administrative staff doing the unsexy work is what makes matching our labor arrangement with the mission and vision of the magazine possible. Michael Falco, executive director of Incite at Columbia University where Logic(s) is now housed, shares a deeply intimate and raw experience of coming out as gay in the Midwest and (erroneously) thinking a university in NYC would be a safe haven via an emoji essay. The emotional power and playful medium demonstrates the kind of relationship we’ve been lucky to negotiate between the magazine and a university that remains the largest real estate holder in New York City and continues to dispossess local residents through eminent domain as well as gentrification.

The Brahmins, Abyssinians, and other Global South postcolonial elites have been very effective at dominating and gatekeeping white institutional resources from those of us with countermemories of settler colonial empire. I’m very proud that we can provide a platform for the oppressed people otherwise systematically excluded from these mechanisms of power to shape discourse—but also social life. We also have a duty to protect, and are eternally grateful for our team of fact checkers and copy editors who have made it impossible to undermine our contributors on the basis of veracity and clarity. We got this little magazine situation funded and in the spirit of André 3000’s proclamation at the Source Awards, “the South[s] got something to say!”6

1. This definition resonates with how Black indigenous people in Africa are described by early settlers and slaveholders:

“darkly; gloomily. wickedly:

a plot blackly contrived to wreak vengeance.

angrily:

blackly refusing to yield to reason.”

“Blackly,” in Dictionary.com.

2. Thinking here with Saidiya Hartman’s writings on the afterlives of slavery and Edouard Glissant’s notions of continuity. There are multiple conversations occurring at multiple registers within and around slavery, these are just two figures.

3. “…the Bakongo cosmogram reverberating in the ‘ring shout’ practices of enslaved Africans and their descendants on the Georgian and South Carolinian Sea Islands.” From Gabriel Peoples’ thesis, ““A Circular Lineage: The Bakongo Cosmogram and the Ring Shout of the Enslaved Africans and their Descendants on the Georgian and South Carolinian Sea Islands,” 2008.

4. Mahmood Mamdani, Neither Settler nor Native: The Making and Unmaking of Permanent Minorities (Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2022); Achille Mbembe, On the Postcolony (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2001); Eric Hobsbawm and Terence Ranger, The Invention of Tradition (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1983).

5. “‘A more open and connected world is a better world. It brings stronger relationships with those you love, a stronger economy with more opportunities, and a stronger society that reflects all of our values,’ wrote Zuckerberg.” From Jessica Elgot, “From Relationships to Revolutions: Seven Ways Facebook Has Changed the World,” The Guardian (Guardian News and Media, August 28, 2015).

6. Thinking here with incoming managing editor Sucheta Ghoshal’s doctoral dissertation on technology in relationship to how the Black US South needs to be explicitly understood as part of the Global South. Additionally, Regina Bradley’s Chronicling Stankonia: The Rise of the Hip Hop South has deeply influenced how we conceive of these very necessary “South to South” conversations.