In November 2016, the British tabloid The Daily Mail published some sensational news: escorts use the Internet just like the rest of us! The paper reported that sex workers had set up a website to rate their clients. With the air of breaking a scandal, journalist Dave Burke described sex workers “comparing notes on clients” and “getting advice on pricing” from each other.

This information was far from new. The online forum in question, SAAFE, had been created by escorts for escorts in 2003. And as Burke himself admitted, SAAFE serves a purpose well beyond rating johns on a ten-point scale. SAAFE stands for Safety and Advice For Escorts, and members use it to share life-saving information about dangerous or unscrupulous clients.

SAAFE provides women who work in a difficult, risk-laden profession a way to avoid men who do not behave appropriately. It is far less about rating the way a man’s breath smells or the size of his penis, and much more about alerting other workers to a client who stole the money back after a booking, or became violent, or ignored boundaries.

But that might not sound quite so shocking to the readers of The Daily Mail.

Unfortunately, a paper running a salacious story on sex workers and the internet is par for the course now. Just one month before The Daily Mail article, Carl Ferrer was arrested. You may not have heard of him, but sex workers across America have. He’s the CEO of the classified listings site Backpage.com, which used to be one of the country’s most popular online platforms for escort ads.

In October 2016 he was arrested, along with the site’s founders, on a range of pimping charges. Ferrer and the founders were eventually cleared because the judge deemed they could not be held responsible for user-generated content. But Backpage still closed down its “adult” section, like Craigslist before it—a move the company called a “direct result of unconstitutional government censorship”. Predictably, the saga garnered sensationalized press coverage.

When the media reports on online platforms like SAAFE and Backpage, it focuses on details designed to titillate an audience that knows little about sex work. It also typically tells the story from the perspective of clients. Only rarely do we hear from the sex workers themselves, who rely on these platforms for their livelihood and their safety.

Selling sex online provides several advantages: a better opportunity to screen clients, a stronger ability to negotiate, and a lot more independence. Online marketplaces give workers the ability to craft ads on their own terms, clearly outlining their services, prices, and boundaries long before a client may even acquire their phone number. And taking payments online—especially through PayPal, where all that’s needed to send money is an email address—is both easy and safer for anyone who might want to avoid providing their bank account information.

“Online advertising provides a level of safety to those in the sex industry that many other spaces do not,” explains Kate D’Adamo from the Sex Workers Project at the Urban Justice Centre. Not everyone can make use of these tools, of course. Sociologist Elizabeth Bernstein describes the kind of workers who have benefited most from online platforms as “overwhelmingly white, native-born and class-privileged women.”

Still, for many sex workers, the impact of the internet is significant—and growing.

Safe Words and Ugly Mugs

Throughout its long history, the sex industry has always adapted to new tools and technologies. “All sexual commerce is technological,” explains Melissa Gira Grant in Playing the Whore (2014). Before the internet, sex workers placed their phone numbers alongside ads in the backpages of magazines and newspapers, or on “tart cards” they left in phone booths. Before the telephone, they carried business cards. In ancient Greece, Gira Grant says, sex workers scored the words “follow me” into the soles of their sandals so that customers could find them.

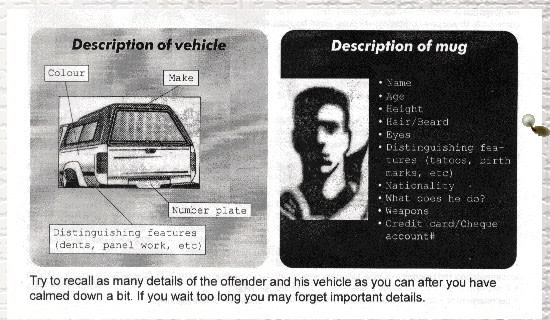

And as far as they were able to, sex workers have always screened clients to filter out dangerous ones. “Ugly mugs,” “bad dates,” or “bad trick” lists were a fixture of the sex industry years before the internet became mainstream. The Prostitutes Collective in Victoria, Australia began their ugly mugs scheme in 1986, and the Alliance for the Safety of Prostitutes in Vancouver started their bad dates list in 1983. In a newsletter from 1995, an escort with the Sex Workers Alliance of Vancouver described how to produce an ugly mugs list:

The format should display the details in a consistent order from report to report. Using a database facilitates this because the fields are in a consistent order in each of the records. The information should be as simple and concise as possible… The shorter and more concise the description of the assailant and incident, the more reports will fit on an issue…

She also recommended using particular software—developing the database with Filemaker Pro 2.0, and publishing the list with Quark XPress. Even before sex workers had online platforms, they were using digital tools to protect themselves.

The most important feature of these lists has always been that they’re produced and distributed by sex workers themselves. Community-based efforts led by sex workers are a pillar of professional safety—not least because the police often abuse sex workers, especially in those countries where prostitution is a crime.

These efforts include not only ugly mugs lists, but a range of other methods for keeping one another safe. “Indoor” escorts—workers who are not street-based—often use a “buddy” or “safe call” system, where a third party—perhaps a friend, driver, or receptionist at an agency—will be briefed with the location and time of the booking, along with the client’s name and contact information. The buddy is told to expect a call just before the booking and just after, with a prearranged “safe word” that will be used by the worker to indicate that they feel unsafe—and a plan to go with it, or if they go AWOL.

Workers also have strategies for evaluating clients beforehand. These include requesting the john’s full name and address to check against an ugly mugs list, or scheduling a phone call before the appointment, or requesting references from other workers.

Feedback Loops

The internet has made it easier for many sex workers to stay safe. While not all workers have access to online platforms, those who do can use them to implement safety protocols with greater speed, and on a far greater scale. Sex workers have always screened clients, negotiated terms, pooled information, and forged networks with other workers. On the internet, they’re able to do all of these things faster and more efficiently than ever before.

One of the biggest advantages of online platforms is how they facilitate client ratings. Ratings are a core feature of the sharing economy, but they’re especially valuable for sex workers who are trying to protect themselves.

If sex work were accepted as a form of labor, the idea of a ratings system might be less surprising. It would be as mundane as the feedback your Airbnb host writes after you’ve stayed at their apartment, or the star rating you’ve acquired from your Uber rides. When someone offers a professional service, especially one that involves being placed in an intimate situation with their customer, it makes the utmost sense that they would want to know from other service providers what that client was like.

Ugly mugs lists served that purpose before the internet—and no doubt still do in some areas—but the digital age has strengthened the ability of sex workers to warn each other of abusive men. One example is Adultwork, an online marketplace for sexual services set apart from the likes of Backpage by being solely for “adult” providers. British dominatrix Margaret Corvid says that sourcing clients from Adultwork gives her more control over the screening process. On the site, workers build profiles describing the services they offer (and do not offer), detail their rates, and display a mixture of professional and candid photographs. Clients then message the workers they would like to meet.

But the major benefit of Adultwork, London-based escort Violet tells me, is the “feedback” system. First and foremost, clients can tell other potential johns whether a worker is who she says she is—and whether she offers the service she says she does. Crucially, however, the rating system works both ways. If other sex workers have had negative experiences with a client, this will be immediately apparent to everyone else.

According to Violet, Adultwork also once employed a “notes” system, where sex workers could leave details about a client that only other service providers could see. It avoided the risk of malicious retaliation from the client, who may have access to a worker’s personal information. After all, sex work is stressful enough.

Violet has left her own notes on Adultwork in the past, including about a client who assaulted her. She explains:

I think nobody wants to speak out about a client who has literally hundreds of positive reviews. But just one person coming forward can encourage others. My note reporting that client was the first, but within two days, someone else had left a report. It opened the floodgates. The online reporting system makes it feel a lot more legitimate. Without it, dangerous clients would just carry on getting away with it, which is what I found out when I reported this client and had other escorts messaging me saying, “Oh yeah, I remember meeting him, he did a similar thing to me.”

Another valuable tool for online screening among British sex workers is National Ugly Mugs (NUM), a digital version of the ugly mugs lists produced by sex worker collectives. Run by the UK Network of Sex Worker Projects, NUM receives funding from the UK Home Office, a branch of the British government. It provides sex workers with a platform to report details of dangerous clients into an online database, which is then used to send alerts via email or SMS to all workers who signed up to receive them.

Violet knows all too well the benefits of NUM, because she reported her assailant there too. “It took me about 6 months before I submitted the report and really came to terms with what had happened,” she explains. “I wasn’t really sure if I wanted to report it as a crime and go through the legal system. I didn’t feel like the police would understand—and even if I had gone down that route, that wouldn’t have made other sex workers aware.”

Given that a lot of people still view rape and assault as merely occupational hazards of the sex industry, it’s not hard to see why sex workers would be anxious about reporting to the police. This is particularly true in countries that have criminalized sex work, where reporting an assault may result in an arrest for the worker. Schemes like NUM put control of the situation back into the hands of workers, and allow them to look out for each other.

Thanks to developers at the Manchester-based “social enterprise” agency Reason Digital, NUM now exists as a smartphone app too. It uses the same geolocation technology as apps like Tinder to push local updates to workers. On Android devices, it even features the ability to screen calls by searching for the incoming number in the NUM database.

The inspiration for the app came from Reason Digital co-founder Matt Haworth’s work with Manchester Action on Street Health, a sex worker support service. They keep an ugly mugs list, but it’s not updated fast enough—in the time it takes to produce a physical booklet, or even to push new information to their website, another worker might encounter the same violent client. The immediacy offered by an app could be the difference between life and death. As project manager Jo Dunning points out, “days lost cost lives”.

Reason Digital worked closely with sex workers from the beginning to develop the app. That’s why the background of the app is black—to prevent the backlight from illuminating the worker’s face and betraying what they’re doing. It’s also why the phone’s location data does not feed back into a database—otherwise, the app could very easily be used to track the movements of sex workers throughout Britain. Users are at liberty to sign up with a fake name, and use a phone number or email address they’ve created exclusively for the service.

One remaining hurdle is accessibility. The app requires a smartphone, and not all sex workers have access to one—especially street workers. During the pilot, Reason Digital handed out smartphones preloaded with the app. But for the NUM app to scale, a more robust solution is required. Either smartphones will need to become so cheap that all workers can afford them—and use them on the street without fear of having them stolen—or sex worker organizations and outreach services will have to distribute them en masse.

Risk Management

While building better tools for screening clients is critical, much of the challenge in keeping safe while sex-working is that so much is retroactive. The buddy system only alerts someone to the fact that something has gone awry after it has happened—which may be too late.

By building a “panic button,” developers may be able to solicit a faster reaction. This idea inspired two medical students, Isabel Chen and Kyle Ragins, and sex worker advocate Vanessa Forro to create the Keep Safe Initiative in 2012. They set out to provide street-based sex workers in Vancouver with a pre-programmed device that used GPS and cellular technology to act as a panic button should they encounter danger. Given that many digital services for sex workers are naturally geared towards independent, indoor providers, Keep Safe Initiative’s emphasis on street-based workers was key.

If technology can improve the safety of sex workers, it can also enhance the security and anonymity of their financial transactions. PayPal has been invaluable for sex workers from the beginning. Indeed, journalist Courtney Boyd Myers claims that when the company first got started in 2001, “some of its first customers were those working in the sex industry.”

The appeal of PayPal for sex workers is obvious. Users can send and receive money through an e-mail address, and don’t have to compromise their privacy by providing bank details. Transacting online also hedges against certain risks. Sex workers regularly deal with the fear of having their fee stolen back from them by their client, or the concern that a client might waste their time by not paying. Prearranging payment through services like PayPal is an attractive alternative.

But using PayPal for sex work isn’t without its challenges. The company has been known to freeze the accounts of any user believed to be receiving funds through sex work. And credit and debit card companies regularly block sites that may be used to facilitate sex work—as Backpage found out.

The Great Normalizer

Ever since Carol Leigh coined the term “sex worker” in the late 1970s, the fault lines of feminism have been drawn along supporting the criminalisation or decriminalisation of the sex industry. Those advocating criminalisation believe sex work is not work but abuse: Gloria Steinem branded it “commercialised rape.” They want the industry to be completely criminalised, as it is in America, or for the client to be criminalised, as it is in Sweden.

Those arguing for decriminalisation, including many sex worker-led organizations worldwide, believe that any mode of criminalisation endangers workers and threatens their livelihoods. They say that sex work is work and should have the labor rights that come with it.

The internet has contributed to this debate by making sex work look more like work. On the internet, sex is just another service for sale. The founder of Citylove.com, San Francisco’s first online adult directory, explained the phenomenon to the sociologist Bernstein back in 2001:

The most important thing about the Internet is that it has hastened the acceptance of adult entertainers as competent people … you can’t ignore them, or pretend that everyone is just a gum-chewing, fishnet-wearing, miniskirted prostitute with big hair and sunglasses.

We all saw that big-haired prostitute played by Julia Roberts in Pretty Woman. It’s a stereotype that the internet has helped erode. “Online sexual commerce had shifted the boundaries of social space,” Bernstein writes, “blurring the differences between underworld figures and ‘respectable’ citizens.” Visiting the Citylove.com office, Bernstein describes its atmosphere as “no different than that of any other new and profitable Internet start-up company.”

The internet has helped normalize sex work as work, in other words. It’s achieved this at least in part by making the sex industry more visible to outsiders. Sex worker visibility on the internet may inspire sensationalism in places like The Daily Mail, but it also offers an opportunity to promote awareness. Social media makes it easier for journalists to contact individual sex workers and their organizations when writing on the subject. Social media also empowers sex workers to forge alliances with other activist groups.

Molly, a sex worker and activist with the Sex Worker Open University (SWOU), calls social media an “incredible tool in building connections between groups and sharing analysis.” Through the internet, groups that are not sex worker-focused—organizations opposing police violence or deportations, for example—can discover the advantages of working with sex worker organizations.

Molly also believes that social media can be formative in developing sex work politics. By enabling sex workers to see how other workers encounter the same dangers that they do, the internet can cultivate a sense of collective identity. Online communities have helped sex worker rights organisations “blossom,” Molly says. “People are aware of how criminalisation harms them in a very personal sense,” she explains. “Once you plug into a sex worker community, you can more easily see the broader patterns; you can see how these harms that you’re experiencing are part of a structure.” That structure is made more apparent by technology—and those harms can often be mitigated by technology as well.

But the additional exposure that the internet brings can also put sex workers at risk. Online platforms may provide workers with safety, convenience, and community, but they come with a danger: surveillance.

In countries where sex work is criminalised, law enforcement will monitor a suspected worker’s online presence. In countries where only the client is criminalised, police will follow sex workers’ online movements in order to track down their law-breaking clients. In the United Kingdom, where sex work in itself is decriminalised, the authorities will use online surveillance to gather evidence against workers for the crime of brothel-keeping—which means simply that multiple workers work from the same building. “Rather than limit their patrol to the street,” writes Gira Grant, “vice cops search the Web for advertisements they believe offer sex for sale, contact the advertisers while posing as customers, arrange hotel meetings, and attempt to make an arrest.”

In response, sex workers must go underground—even at a time when their industry has never been more public. Secret, invite-only groups on Facebook help keep conversations among sex workers away from prying eyes. There, workers exchange tips, discuss experiences, arrange meetups, and share information ranging from dodgy clients to which sex toy store offers discounts for industry professionals. On Twitter, there are glossy, client-facing accounts and anonymous, locked accounts—and a thriving support network in the DMs. Only word-of-mouth will lead you to these spaces—so unless you’re a sex worker, it’s more than likely you haven’t seen them.

An escort named Suzie tells me that she uses forums like SAAFE, but that she finds the underground social media groups much more “cohesive.” “There’s something more intimate about belonging to a network of workers who are local to me and part of a wider community too,” she explains. Molly reiterates this point. “These are community spaces,” she says. “There’s generally someone awake if you need to reach out at 3am, you know?”

These spaces offer emotional support for workers dealing with a range of issues, from handling sexual violence to managing dating and relationships. They also offer friendship. Suzie says before she joined a Facebook support group, she had no sex worker friends. Now, they’re the “virtual cornerstones of my support networks.”

But as with everything in the sex industry, even these secret social media communities aren’t immune to surveillance. Facebook’s algorithms have a nasty habit of flagging up all kinds of information about your activity to your wider network of “friends,” and are fond of suggesting that you add the most random of your phone contacts. “Many people use the networks via their real name accounts,” Suzie explains. She doesn’t. “I’ve seen people get into tricky situations and come close to being outed.”

Still, for many workers, the risk is evidently worth it for the support these spaces provide. Sex work can be a lonely job.

No Shortcuts

However transformative, technology has its limits. It can revolutionize many aspects of sex work, but it cannot sanitize the experience of providing sexual services for workers who physically share space with clients. Sex work by its very nature will always be high risk.

And while projects like NUM are taking great steps towards digitizing sex worker safety methods, the criminal status of the industry means that developers are unlikely to lead the way. A lot of workers would rather not engage in behavior that could be traced back to them, like downloading apps to their phones. In the United States, the slightest bit of carelessness could lead to a criminal conviction. Even in places where sex work is less criminalized, it could result in unwanted police attention.

Still, there’s no doubt that technology has played an empowering role in the lives of many sex workers. It’s given workers new tools for transacting, for building community, and for protecting one another. While the underlying practices aren’t new, the internet has enabled them to be implemented with unprecedented speed and scale.

Sex workers today are simply doing what sex workers have always done, just with different tools. Taking those tools away doesn’t mean sex work disappears. It means sex workers go back to whatever it was they did before—only without the many advantages that technology can provide.

If that seems preferable, you may not have their best interests at heart.