In 2008, an internet porn company called the Adult Entertainment Broadcast Network (AEBN) announced an innovative product that it promised would revolutionize how men masturbated. Dubbed the RealTouch, the device fit over the penis and connected to the user’s computer via USB. As the wearer watched videos specially encoded for use with the RealTouch, belts inside the machine spun and tensed, its heating elements warmed, and it dispensed controlled bursts of lubricant—all synchronized with the actions occurring onscreen.

Although the RealTouch initially worked only with pre-encoded videos streamed from the company’s servers, the addition in 2012 of the “JoyStick” controller allowed the user to be remotely manipulated in real time, typically by a female worker who connected through a network called RealTouch Interactive. In spite of several attempts at providing content that would appeal to gay men, AEBN targeted the RealTouch primarily toward heterosexual males.

By the end of 2013, the machine had begun to capture the public’s imagination, and started getting coverage in tech blogs. With the hype gaining steam, the RealTouch appeared poised to fulfill the lofty promises that had been made about cybersex ever since the writer Howard Rheingold popularized the term “teledildonics” in 1990 to envision the possibility of fully embodied computational sex—riffing on computer visionary Ted Nelson’s idea of “dildonics,” offered way back in 1974.

The apex—or climax—of the device’s popularity and public visibility came in January 2014, when the machine was featured in the HBO late-night documentary Sex/Now. For only $200—which included free credits for streaming encoded videos over the RealTouch servers, lubrication cartridges, and cleaning fluid—men could buy the device, described on its Amazon product page as a “High-tech Interactive Virtual Sex Simulator.” However, the same month it debuted on HBO, AEBN—mired in an increasingly expensive patent dispute over the product—halted production of both the RealTouch itself and the vital replacement parts required to keep the device functioning properly. Having sold off the remaining units, the company posted a eulogy for the device, beaming with pride at the RealTouch for “cementing its place in the history of adult entertainment.”

It might be tempting to dismiss the RealTouch as another failed attempt at realizing the far-fetched and perpetually deferred fantasy of teledildonics, or to giggle at the absurdity of both the device and its users, or to condemn it as a participant in an industry that objectifies women. But indulging such impulses prevents us from understanding what the RealTouch was—and why it matters. As Marshall McLuhan eloquently put it, “resenting a new technology will not halt its progress.”

The RealTouch wasn’t just a complex technical system—it was also an economic strategy and a set of social relations among networked subjects performing a new form of digitized sex work. Each of these factors—the machine’s mechanics, its economics, and its affiliated labor practices—were oriented toward the goal of creating the cybersexual real: the promise to replicate the feel of sex by stimulating the senses of seeing, hearing, and—most crucially—touch. AEBN’s engineers worked hard to build a machine that functioned so effectively that it would make the wearer feel as if they were penetrating “the mouth, vagina, or anus of a real human,” and the company frequently boasted of creating “the most lifelike simulation ever.”

Over the centuries, technological innovation has made it possible to automate the production of an ever-growing number of goods, from clothes to chemicals to cars. With the RealTouch, AEBN aspired to automate the production of male orgasms.

You Can’t Pirate a Rollercoaster

When AEBN first hatched the project, they had over 100,000 pornographic videos in their stable, spanning an impressively wide range of genres. Like others in the adult video industry, however, AEBN faced the threat of declining revenues due to unauthorized copying and downloading. The company had compounded the problem in 2006 when it launched the streaming site PornoTube, intended to be “the YouTube of porn.” PornoTube was supposed to encourage users to pay for online porn. Instead, it sparked a number of imitator sites, where people reposted paid content from AEBN. CEO Scott Coffman would later call the decision to start PornoTube “the worst thing I’ve done since I was in the adult business.”

So when inventor Ramon Alarcon approached AEBN with a wooden prototype of what would eventually become the RealTouch, the company saw it as a potential salve for a wound that had been, to some extent, self-inflicted. Alarcon held a Masters in Mechanical Engineering from Stanford. He had spent eight months interning at NASA all the way back in 1993 and five years working for the Immersion Corporation, a company based in San Jose that had cemented its status as a leader in “haptics”—the use of computer-controlled mechanical cues to provide the illusion of touch.

Executed successfully, Alarcon’s idea could provide a way for the company to differentiate and defend its intellectual property: by layering touch sensations onto pre-existing audiovisual content, the RealTouch would add value to AEBN’s vast library of videos. As Coffman explained in a 2010 press release, by “delivering the sensory dimension of touch,” the touch-encoded videos streamed from the company’s servers would prove more resistant to piracy. “You can pirate the movie,” as Coffman put it, “but you can’t pirate the experience. It would be like trying to steal a roller coaster.”

For the copy-protection scheme to succeed, however, AEBN had to entice potential customers to boldly take that first step onto the rollercoaster. At the Adult Entertainment Expo in 2009—the porn industry’s annual convention, piggybacked onto the Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas each January—the company blitzed the showroom floor, with models pitching the machine as the next generation of online porn. AEBN touted the scientific sophistication of the design process, referencing Alarcon’s thin NASA credentials frequently, and featuring the machine’s use of haptic technology (defined as “the science of touch”) prominently in their marketing materials.

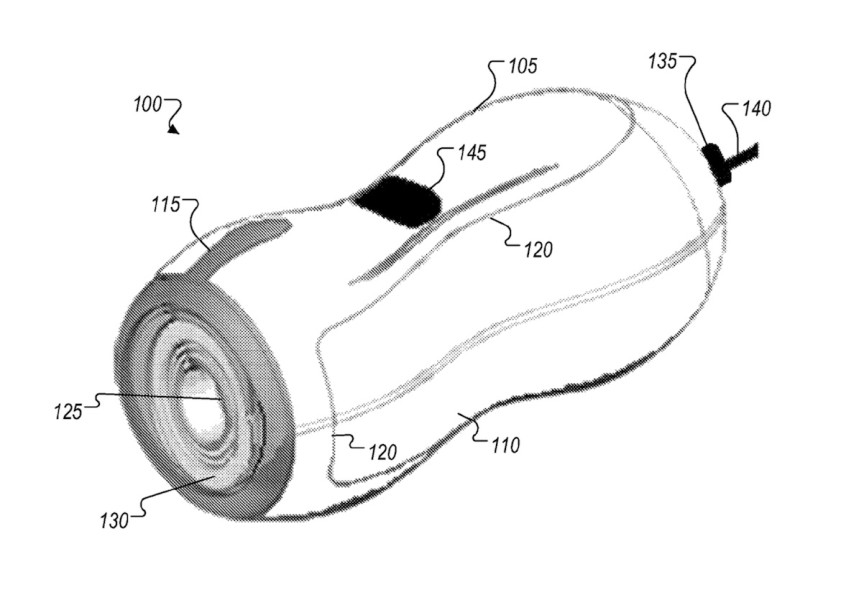

An interactive graphic on the RealTouch’s product site offered a peek inside the device, showing the separate mechanisms used to produce sensations of heat, lubrication, tightness, and friction. The core components were two spinning belts that simulated a human orifice. These were surrounded by “highly-specialized, custom-made material” that provided a “realistic texture,” making it “the closest thing to actual skin.” The exterior had a white-and-grey color scheme that echoed the visual aesthetics of the then-popular WiiMote videogame controller, positioning the RealTouch at the bleeding edge of technological advancement. In another promotional graphic, AEBN depicted the RealTouch at the end of an evolutionary chain of online porn. The implication was that adding the tactile dimension would make everything else seem primitive by comparison.

But the biggest selling point of the RealTouch had nothing to do with its physical properties. AEBN wasn’t just promising a pleasurable sexual experience, but an emotionless one. The company claimed that the sex provided by the RealTouch came without the perceived baggage, messiness, and uncertainty of interacting with a real flesh-and-blood woman. According to AEBN, men could order orgasms on-demand—without hazarding the complexities of intimacy, or the risk of rejection. In a promotional video, product manager Scott Rinaldo contrasted the perpetual willingness of the machine with the fickleness of a human romantic partner. “It never gives you an attitude,” he told his audience, “and it always says yes.”

The Labor of Haptification

The RealTouch’s financial success hinged on the willingness of users to shell out fifty cents a minute to stream touch-encoded videos. But haptifying AEBN’s vast library of videos was no small undertaking. The company assigned the task to a handful of male coders, who moved scene-by-scene through each video. They imagined what each sexual act would feel like on their own genitals, and then translated those sensations into code using the Real Touch’s proprietary effects-editing software. The highly complex process required the coders to assign numerical values to each of the device’s mechanisms—the heating elements, the belts, and the lubricant dispenser—to create a tactile experience appropriate to the onscreen image. By manipulating the different components, the programmers emulated the sensation of a mouth, a vagina, or an anus.

According to “EJ,” a product manager for the RealTouch, the coders kept the machine on their desk when working. “By having a RealTouch available during the encoding of the movie, they could, in real time, adjust what command seemed to replicate the action on the screen,” EJ told me. They often left the guts of the device exposed, so that they could see the motion of the belts change as they manipulated the coding for a given scene. Blending effects drawn from a bank of over 200 different haptic “events”—pre-programmed combinations of values that produced specific actions—allowed the programmers to ensure that each scene provided the end user with a unique experience.

Enterprising coders “came up with ways to move the belts that weren’t even originally envisioned, just by tweaking the velocity and duration of the belt movements,” says EJ. Working in a sterile corporate cubicle farm, however, meant that the coders never tested scenes directly on themselves. Instead, they inserted their fingers into the machine to serve as a surrogate for their genitals.

Adding touch data to a sufficiently large body of content presented an immense challenge for the small team, as they embarked on an ambitious project with few precedents in the history of computing. But despite the device’s exoticism, coding for the RealTouch wasn’t all that different from working with normal video editing software. It could be routinized and mastered with enough training, allowing a skilled programmer to encode a five-minute video in roughly thirty minutes. By 2012, AEBN’s streaming library included over 1500 touch-encoded videos, organized both by category (“Big Tits,” “Teen,” “Blonde,” “M.I.L.F.”) and by sex act (“Blowjob,” “Doggy Style,” “Cowgirl,” and, of course, “Reverse Cowgirl”). Although the videos varied widely in content, they shared a first-person camera angle that provided a unifying visual aesthetic, aligning image, sound, and touch with the male actor’s perspective.

The repeated use of this first-person perspective required the coder to engage in an odd process of haptic identification. He had to imagine not just what the action onscreen felt like for the male actor, but also how the programmed scene would feel for the device’s wearer when the hardware enacted it. Sometimes, fidelity to the former frightened the latter. As one reviewer noted, “the ultra-faithful coding makes one thing abundantly clear—male pornstars’ penises do not receive gentle treatment from their female colleagues[…] It’s a full throttle sensory onslaught that’s almost a little scary.”

At its core, the RealTouch aimed to automate the manual labor of male self-pleasure. For all its cutting-edge qualities, it belonged to a long tradition of devices that tried to mechanize masturbation, dating back to at least the nineteenth century, when doctors developed steam- and electricity-powered vibrators to treat “hysteria” by bringing female patients to orgasm. But the rhetoric of automation—frequently mobilized in the RealTouch’s promotional materials—concealed the immense amount of labor required to materialize the cybersexual real. The machine might have saved a lot of labor for its user, but it created a new, complex form of work behind the scenes. Or, as one commentator put it: with the RealTouch, “it takes a village to get you off.”

Stroking From a Distance

After several years in development, AEBN debuted the JoyStick controller for the RealTouch at a sex tech party thrown by the porn company Pink Visual near the 2012 Consumer Electronics Show. The controller allowed its operator to remotely manipulate the RealTouch, so that their movements would be felt in real-time by the device’s wearer. As the (typically female) operator stroked the JoyStick, sensors relayed the operator’s movements to the RealTouch, causing its belts to spin and its orifice to tighten in response.

The JoyStick was nothing short of a technological marvel. While the RealTouch represented an impressive first step, some people at AEBN felt that it should’ve been further refined before being released. The JoyStick, by contrast, embodied a half-decade of research and millions of dollars invested in development. The controller featured seven sensors distributed around a phallic computer-connected device, along with buttons that could be used to adjust the RealTouch’s temperature and lubrication.

The team that built the JoyStick consisted of five male engineers with training from a range of elite institutions, including Stanford and MIT. During the extensive design process, they experimented with over fifteen sensor placement configurations before arriving at a distribution pattern that allowed for precise, high-resolution control over the remote unit. Along the way, they overcame the monumental design challenge of building electro-capacitive sensors that would be capable of functioning in what EJ described as “wet environments”—the heavily lubricated orifice of the RealTouch—while still providing seven bits of resolution and refreshing forty times per second. The product’s success hinged on achieving a degree of fidelity that would convince the RealTouch wearer that the distance between him and the remote body manipulating the JoyStick had disappeared.

At launch, Rinaldo laid out a bold long-term vision for the system, claiming that the RealTouch/JoyStick pairing could allow couples in long-distance relationships to have more meaningful intimate encounters during their time apart. In a claim that quickly circulated on tech blogs, he promised “a thousand dildos for the military wives,” boasting that AEBN would eventually donate the product to US servicemen stationed abroad and their partners. Such a move, Rinaldo acknowledged, would’ve entailed a massive rebranding of the system: the RealTouch’s promotional materials would have to be “de-pornified,” and reoriented towards romantic, couple-centered imagery. It was a smart marketing ploy, but AEBN never put the resources into making it a reality.

While an extraordinary piece of technology, the JoyStick wasn’t just a device. It was also a business model. Immediately upon releasing the product, AEBN launched the RealTouch Interactive (RTI) Network to provide a system for monetizing it. The RTI Network consisted of hundreds of “cam girls”—women who perform paid live sex acts via webcam—willing to add touch feedback to their video streams with the JoyStick. To entice women to join the network, AEBN claimed that using the JoyStick would help them differentiate their video streams in a competitive marketplace. They would be able to form stronger affective bonds with their customers, and thus charge higher rates for their labor.

Dubbed “the world’s first digital brothel” by the tech blog Engadget, the RTI Network lured workers by promising to empower them. They could set their own rates and rules, and reap the benefits of a machine that fostered client satisfaction and loyalty. RealTouch’s official Twitter feed promoted members of the RTI Network, imploring customers to “pop” the “RealTouch cherry” of workers who were new to the network. AEBN ran the RTI servers, and provided the JoySticks for free to the cam workers—although the company took a cut of whatever revenue the women’s streams generated. Rates for oral sex ranged from $30 to $60, while a 30-minute session that featured full penetration cost as much as $219.

While Rinaldo had tried to pitch the JoyStick as a system that could provide pleasure for both participants, decisions made in the design process reflected AEBN’s strategy for commercializing the device. When asked why the initial version of the JoyStick lacked any sort of vibration feedback to stimulate the women who would be operating it, Rinaldo admitted that the device was built to be a gendered labor machine. He crudely explained that, for the cam girls, “their job is not to get off. Their job is to service guys all day.”

A Girl in Romania

Like its predecessor the RealTouch, the RTI Network commercialized the robotic production of male orgasms. But unlike the video-on-demand system, with its pre-encoded streams of haptic data, the RTI Network required touch sensations to be created dynamically in real time. Cam workers, then, were effectively doing the work that had formerly been executed by a small team of male coders—performing a mode of effects editing, configured by the material specifications of a machine interface that expressed a set of patriarchal power relations.

Authoring multimedia content always involves the fusion of authors with authoring tools, as creators work within the platform’s enabling constraints. The RealTouch was no exception: male coders, drawing from a bank of presets, drew upon their existing knowledge of effects-editing suites to develop new combinations of sensations. Female cam workers, building on their experience with previous forms of technologically-mediated sex work, could experiment with the device to see which actions resulted in the most positive responses from their male customers.

In the case of the male coders, however, their labor was defined by its invisibility and anonymity: neither the design team who worked on building the RealTouch nor the coders who haptified content for it were identified by name in the videos that featured their work. The LinkedIn page for Alarcon, the RealTouch’s inventor, contains no reference to his work on the RealTouch—except for a link to the patent “System and method for transmitting haptic data in conjunction with media data.”

The female workers, by contrast, were defined by their spectacular visibility. They had to make themselves as seen as possible: not only by advertising themselves on the RTI Network, but by showing their naked bodies on camera. Moreover, the technology that configured the cam sessions enforced a unidirectional visibility: the woman operating the JoyStick could be seen by the remote male who donned the RealTouch, but the platform did not allow her to see him back.

She even lacked the capacity to sense the man’s level of arousal through the interface, so the user had to indicate it either through text-based chat, or by clicking one of five icons that showed the male sex organ at different stages of stiffness. To help the worker understand the relationship between her movements and the undulations of the remote RealTouch, an onscreen display represented the position and force of her body as it moved across the JoyStick, providing an oddly disembodied visualization of her interiority.

Sex, like computing, puts one body in a feedback loop with another. Each body sends signals to the other, and each modulates its actions accordingly. But with cybersex, which overlays the principles of computing onto sex, the feedback cues are configured by the interface’s materiality—a materiality itself configured by the surrounding economic system.

Within the enabling constraints of the RTI Network, the cam worker cultivated an intimate, cybernetic relationship to the sensors distributed throughout the device, to the algorithms that rendered her movements visible and tangible, to the latency of the network that transmitted her commands, and to the body of the subject that she labored on. Her labor generated revenue for AEBN, by producing a simulated sexual experience for a paying customer. But the simulation, for all its attention to realism, omitted a crucial aspect of sex. If sex involves two people both giving and receiving sensation, the RTI Network imposed a different division of labor: the female worker gave the sensation, and the male customer received it. This reflected AEBN’s vision for the future of technologized sex, articulated most pointedly by EJ in HBO’s 2014 Sex/Now feature:

We’re going to take sex over the internet into the future. Sex over the internet started with still images, then you could download a video clip. So what is the next thing? The next thing is being able to actually have sex over the internet[…]We’ve always said that on that day when a girl in Romania can reach out and touch your penis, that’s the beginning of something completely new.

EJ expresses a variation on a familiar techno-utopian theme: networked digital technology will destroy the gap between bodies separated by geography, nationality, gender, class, and age. But this new proximity would come on very specific terms: the future will have arrived once the female can reach out to manipulate the male for his sexual pleasure, not for her own.

Although the company promoted the device using scientifistic jargon that suggested a devotion to achieving some absolute standard of fidelity to the haptic real of sex, the RealTouch Interactive produced instead a particular, heterosexual male fantasy of female sexuality—one where the female body was reduced to particular configurations of effects on the male sex organ. AEBN’s promise to recreate the real through a computer simulation was betrayed by the hard-coded materiality of interface—by the machine’s inability to send sensations back from the male to the female he was supposedly having sex with. The simulation, bound up with patriarchal ideologies of sex work, only stretched so far: a girl in Romania could reach out and touch the male, but the technology ensured that she couldn’t feel what she touched.

Reformatting Sex

In the wake of the patent dispute that prompted AEBN to abandon the project, the RealTouch has enjoyed a curious afterlife. AEBN’s 2012 decision to strip the RealTouch of its Digital Rights Management opened up the device to user-generated content, spawning an active community that encodes videos using the OneTouch authoring platform. And a range of male-oriented toys similar to the RealTouch—such as the Vorze—have taken up its mission of synthesizing a cybersexual real by synchronizing visual, audio, and haptic data. Although AEBN shuttered the RTI Network in the fall of 2015, the age of internet-connected, remotely-controlled sex toys—playfully referred to as the Internet of Dildos—is only now beginning to take shape.

Dystopians will fret that this new mode of intimacy dehumanizes and degrades, reading the embrace of computer-mediated sexual touch as yet another indicator of humanity’s descent into machinic enslavement. Techno-utopians and transhumanists, building on Howard Rheingold’s original vision of teledildonics as a technology of liberation, will insist that telepresent sex provides a safe, transformational, and empowering alternative to the real thing. By freeing the self from the constraints imposed by its environment, and by removing whatever limits the physical body places on an individual’s ability to experience their preferred form of sexual pleasure, teledildonics—as Rheingold imagined it—promised to wipe away the old model of sexuality, replacing it with a revolutionary mode of technologically enhanced sex that would be blissfully free from all the messiness that bodies brought with them.

One of the messiest bits of sexual contact between humans is its tendency to serve as a vector for the transmission of disease. It’s no accident that Rheingold’s proposal for a tool that would permit the sensations of real contact while shielding romantic partners from the deadly risks of skin-to-skin intercourse emerged in the Bay Area during the height of the HIV/AIDS crisis. With the computer acting as prophylactic shield, sex could be both pleasurable and disease-free.

Propagated in the psychedelic pages of the magazines Mondo 2000 and Future Sex, this networked sex would also throw the conventional borders of the body into disarray. What if, Rheingold speculated, you could “map your genital effectors to your manual sensors” so that it would be possible to experience “direct genital contact by shaking hands”? Such reconfigurations held the potential to revolutionize everyday interpersonal interactions: “What will happen to social touching when nobody knows where anybody else’s erogenous zones are located?” The transhumanist vision of sex, rejecting the binary opposition between humans and machines, embraces these creative augmentations and re-mixings of conventional intercourse, as it pushes for the further decoupling of sexual pleasure from procreation.

Although the “portable telediddlers” of Rheingold’s fantastical imagination have yet to achieve the ubiquity he forecasted for them, this future has arrived in scattered fragments, slowly remaking the world in far more pedestrian ways than an earlier era of cyberpunks had hoped. The RealTouch—one of the most fully realized implementations of teledildonics—demonstrates the technology’s potential, while also highlighting problems with its development that were invisible to the generation of cyber-utopians who peered into the future through the tint of mirrorshades.

Above all, the RealTouch represented the absorption of teledildonics into a system of capitalist exploitation and value-extraction. In spite of its technical sophistication, the device ultimately functioned as an economic machine—one that generated value for AEBN through the labor of the coders and cam workers tasked with producing the cybersexual real, while also expressing, in the configuration of the technology itself, a set of gendered power relations. Cutting through the marketing hype and moral panic, the RealTouch appears in retrospect neither dystopian nor utopian, but instead merely mundane and mechanistic—a one-way masturbation tool that required an immense amount of labor to engineer, enact, and sustain.

This piece includes material from Chapter Five (“The Cultural Construction of Technologized Touch”) of the author’s forthcoming book, entitled Archaeologies of Touch: Interfacing with Haptics from Electricity to Computing *(University of Minnesota Press, 2018).