“That’s right, little circles… That feels good. Don’t stop…” A sultry voice guides me as I make looping strokes on my MacBook Air Multi-Touch Trackpad with my fingertip, sending corresponding ripples across the lifesize vulva on the screen. I trace rings on the Trackpad and the voice coos, “Yeah, little circles around my clit. Mmmmmmm.”

Risking carpal tunnel syndrome, I’ve spent hours stimulating virtual vulvas on OMGYes.com, a website that aims to “lift the veil on women’s sexual pleasure,” as explained on its landing page in elegant neutral shades. The company was founded in Berkeley by a pair of friends, a self-described straight man with a background in neuroscience and public health (Rob Perkins) and a lesbian artist (Lydia Daniller), who partnered with researchers at Indiana University and the Kinsey Institute to design a sex-education platform “distilling the insights of over 2000 women, ages 18-95, into open, honest videos of everyday women sharing from experience—no blushing, no shame.” OMGYes wants to help women and their partners understand their bodies, what gives them pleasure, and how to get it—how to “make a good thing even better.” It launched in December 2015 with private funding, and it currently has 125,000 subscribers who pay $29.99 for a year’s unlimited access to the site.

The debut “season” of OMGYes focuses on techniques of genital touch divided into twelve episodes. In a series of short videos, approachable, articulate, and racially diverse women describe their erotic preferences. Then, in a second set of videos, they demonstrate how they masturbate while narrating to the camera. Flattering mid-angle shots alternate with extreme close-ups. Each episode emphasizes a particular technique—“edging,” “hinting,” “signaling,” or “orbiting,” for example. These videos are followed by OMGYes’s killer app: eleven interactive screens displaying digitized recreations of individual women’s vulvas. The viewer uses the mouse to stroke, rub, and caress in specified patterns while coached by the voice of the woman whose nether regions he or she is manipulating.

Although users receive real-time feedback, it’s all recorded content, not live-camming. And while the screens display the patterns of touch traced by the user’s mouse, they can’t offer true tactility or texture, which would tip the experience closer to realism. The feedback loop is limited to verbal commands and touch: all the other bodily cues used to communicate during sex are missing, although many of the women discuss body language in their videos. Still, OMGYes pointedly states that it uses 256-bit encryption: “We pride ourselves on not even storing any personal information of our users.”

OMGYes is among the most high-profile of several female-centered “sextech” platforms whose mission is “demystifying” female sexuality. These include HappyPlayTime (“Making Female Masturbation Friendly”), PlsPlsMe (“A Sexy Game for Making Intimacy Fun”), O.school (“a shame-free platform for pleasure education, centering women and gender-diverse people”), and others in the works such as the Lioness vibrator (“empower[ing] women to learn about their own bodies and… break longstanding taboos around female sexuality”).

OMGYes and its peers hope to enlighten their users about sexuality through “hands-on” virtual platforms. But in the case of OMGYes, that platform is web-only: there is no mobile app. This is the case for many sextech platforms, since Apple’s “Objectionable Content” code bans:

Overtly sexual or pornographic material, defined by Webster’s Dictionary as “explicit descriptions or displays of sexual organs or activities intended to stimulate erotic rather than aesthetic or emotional feelings.”

Who is to say which feelings—erotic, aesthetic, or emotional—are aroused in users who gaze between a pair of spread legs and attempt to please a virtual woman? Are erotic, aesthetic, and emotional feelings mutually exclusive? And where is the line between explicitly and suggestively sexual? These I-know-it-when-I see-it judgment calls by big tech companies are only one of many institutional obstacles facing sextech entrepreneurs. Others include the difficulties of attracting VC funding and advertisers—currently, OMGYes only advertises on Facebook—and convincing banks and credit card companies to process payments for a product that might be perceived as pornographic.

Don’t Overthink It

Despite the challenges, sextech has the potential to be big business. The VC fund 500 Startups estimates that it’s a $30.6 billion field—although what qualifies as sextech is up for debate. As Kate Bevan points out in Wired, “it’s unclear at what point sex toys and devices become sextech.” Indeed, OMGYes cofounder Perkins bristles at the term. He is keen to distinguish the site from porn and smart sex toys such as the We-Vibe (the vibrator company that recently reached a $3.75 million class action settlement with users over allegations of spying), and he considers other sextech ventures to be “separate from the real, vulnerable bedroom sex we each actually have and all the associated feelings and complexities.”

One of the ways OMGYes tries to capture those “feelings and complexities” is through pop psychology and self-help lingo. Its episode on “Framing,” for example, tackles what D. H. Lawrence called “sex in the head”: an overly self-conscious approach to sex. “For many women,” OMGYes explains, “thinking about getting to orgasm can make it impossible to get one.”

OMGYes takes its own advice: it never overthinks. There is a mood of gentle humor throughout. The women speak in tones that are slightly neurotic but always soothing. In the episode “Signaling,” one woman reminds us to keep things light: “This is not mathematics… It’s sexy time.” All of the advice is smoothed out, generalized, and conventional. There’s nothing kinky about any of it. The women talk about awkwardness around sex, but they are relentlessly upbeat. And they never broach the more serious reasons women might have sexual discomfort, such as assault, shame, or other kinds of trauma.

Even the centerpiece of the OMGYes experience—the touchable interface—is distinctly unkinky. Perkins and Daniller decided that the “encounter” between OMGYes’s users and the site should feel like a friend sharing information rather than a dynamic between lovers. (“Aesthetic or emotional” versus “erotic” feelings, to borrow Apple’s distinction.) Moreover, the designers purposefully avoided narratives of gaming that are organized around a player striving to “score” or win. (The “mindful game” app La Petite Mort is an intriguing contrast, as its users touch abstract, pixelated vulvas to produce climaxes.) With OMGYes, there are no bells or whistles to indicate orgasm. Users know they’ve been successful when the woman sighs and the screen closes out.

But the mechanics of the technology are undeniably impressive: after you get over the initial surprise and weirdness of being up close and personal with a stranger’s labia rendered in such high resolution that it verges on the uncanny valley, the interface is actually quite inviting. It took Perkins, Daniller, and their team years to get the touchable screens right. The pipeline involved an unusually intimate and trusting collaboration among engineers, photographers, and the women who are the stars of OMGYes. The interactive genital screens started as thousands of still photographs of women touching their vulvas in different ways. Then the women recorded audio feedback that was mapped to many possible touch inputs.

So, for example, when a user accurately follows the motions that the woman suggests, they get a positive verbal response: “That feels good.” When the user is a bit off-base, an encouraging, constructive voice makes suggestions: “Try going slower.” (A helpful graphic pops up to show the direction and placement of the touch.) An erratic or aggressive touch elicits a sharper response: “Careful, too fast.” If the user persists—and it takes quite a bit of deliberate misconduct to get to that point—the woman’s voice eventually says, warily, “Okay,” and her hand descends to cover her genitals, and the screen closes out. It’s a surprising moment of consent education between a real user and a virtual presence, and a commendable feature in a platform that otherwise strives for an I’m-okay-you’re-okay vibe.

The Unfinished Revolution

OMGYes has been met with mostly positive press. Peggy Orenstein, author of Girls & Sex: Navigating the Complicated New Landscape, plugged OMGYes on Gwyneth Paltrow’s lifestyle website Goop, praising it as a tool for “orgasm equality.” The actress Emma Watson enthusiastically told Gloria Steinem about OMGYes onstage at a talk in London. This year OMGYes is a finalist for two Webby awards, in both the “Health” and “Weird” categories. And The Times of London placed OMGYes at the forefront of “the next wave of an unfinished sexual revolution.”

Unfinished? Sure, there’s the stubborn gender wage gap and the continued division of labor in which women still do most of the world’s unpaid work, but didn’t second-wave feminism already “lift the veil on women’s sexual pleasure”? Wasn’t that a cornerstone of 1970s consciousness raising, of women sharing books such as The Boston Women’s Health Book Collective’s Our Bodies, Ourselves (1971), Alex Comfort’s The Joy of Sex (1972), The Hite Report on Female Sexuality (1976), and Betty Dodson’s Liberating Masturbation (1974) and Sex for One (1987)—all of which encouraged women to get to know their bodies and claim reproductive and erotic agency? If women’s sexuality and “the uses of the erotic as power” (as Audre Lorde put it in her essay by that title) were priorities in second-wave feminism, what happened? Why are the phrases that OMGYes uses on its site, such as the “the taboo around women’s pleasure” and “the complexity” of female sexuality, still resonant in 2017? Why is there even a market for sextech products such as OMGYes?

Forty years after feminist sex education of the 1970s, the “problem” of women’s sexuality persists, apparently, but it has a new name: the “orgasm gap.” To be sure, ever since sexologists such as Masters and Johnson studied men and women’s orgasms, there has been a marked differential. Indiana University’s 2009 National Survey of Sexual Health and Behavior found that 91 percent of men reported that they had an orgasm during their last sexual encounter, but only 64 percent of women could say the same. Elisabeth A. Lloyd’s study The Case of the Female Orgasm: Bias in the Science of Evolution concludes that a third of women never orgasm during intercourse. The picture becomes more telling once the data is broken down: lesbians do substantially better in the orgasm stakes than straight or bisexual women. Culture, more than nature, is at the root of the orgasm gap.

But while the underlying asymmetry isn’t new, the phrase “orgasm gap”—which has been trending vigorously since 2011—implies that women’s sexual pleasure is a problem of economic scarcity and competition. Sociologist Paula England insists that the “orgasm gap is an inequity that’s as serious as the pay gap, and it’s producing a rampant culture of sexual asymmetry.” Whether or not that’s true, sextech and Big Pharma have both been eager to capitalize on the idea that women are in need of some serious orgasmic intervention.

Why does female sexual pleasure continue to be framed as an enigma, a challenge, a gap, a “cipher,” as Annamarie Jagose has described the twentieth-century representation of orgasm in her book Orgasmology? Why, many decades after second-wave feminism, are women still contending with obstacles to sexual pleasure? Why are some still faking orgasms, contributing anonymous confessions about their troubled sexual history to the Tumblr page howtomakemecome, and seeking out sextech solutions?

OMGYes explains it like this: “complexity gets confused for ‘unknowability,’” women’s sexuality hasn’t been sufficiently researched, pop culture spreads misinformation, “there’s no specific, reliable source of information,” and there isn’t yet a sufficient shared language about women’s sexuality. In keeping with its buoyant approach, OMGYes does not mention the orgasm gap statistics. It is also careful not to fetishize orgasm as the only goal—instead, orgasm is one possible event in a broader spectrum of sexual pleasures. And yet the business clearly benefits from the panic around the orgasm gap: despite OMGYes’s cheery tone, it is widespread anxiety about female sexual pleasure that draws users to the site.

A Public Health Crisis

Sextech capitalizes on the market opportunity created by the failure of two vital cultural forces—feminism and sex education—to harness technology. Second-wave feminism promoted the organic, the natural, and the bodily: the classic exploratory technique in the 1970s involved putting a hand mirror between one’s legs. The birth control pill and legalized abortion revolutionized sexual practices, but mainstream feminism did not make technology a central part of its own innovations until relatively recently. When Donna Haraway’s Cyborg Manifesto appeared in 1984, it was an academic novelty, far ahead of its time.

Sextech may help fill the void left by second-wave feminism’s aversion to technology, but it’s careful to avoid the term. Sextech ventures typically do not advertise themselves as feminist or use the language of feminism in their mission statements. OMGYes steers clear of the word “feminism,” Perkins tells me, because it doesn’t want to “limit” its audience, which it claims is 50% women and 50% men. If those statistics are accurate, then OMGYes has attained a gender balance that neither pornography nor sex education have achieved.

American sex education hasn’t kept pace with the technological savvy of the students it addresses. It continues to be taught in public schools through teacher-led face-to-face group conversations about the birds and the bees, usually with boys and girls separated. But sex ed is not only low-tech—it’s also astonishingly low-content. Only thirteen states require that curricula be medically accurate. While Obama had moved to defund abstinence-only programs, they remain firmly in place.

The notion that sex might be fun barely registers: although UNESCO’s 2009 guidelines for sex education states that fifteen to eighteen-year old students should learn “key elements of sexual pleasure and responsibility,” recent surveys in the US, the UK, and Australia have demonstrated that students in those countries rarely emerge from sex ed with adequate guidance about sex as a practice of pleasure. Inevitably, lackluster sex education seems to have impacted women much more than men. The Guardian’s series “The Vagina Dispatches,” one of numerous recent demonstrations of the general public’s pitiful knowledge about women’s sexual anatomy, reported that “just half of women aged 26-35 were able to label the vagina accurately.”

Given the pathetic state of sex education, the porn industry has become the default sex-ed provider, making full use of the digital resources neglected by the traditional sex-ed system. With its unprecedented level of accessibility, internet porn is a primary source—some say the primary source—of information about sex for audiences it was never meant to reach, including children and teens. Porn has essentially become a 24/7 X-rated MOOC (Massive Open Online Course). Perhaps the most convincing contemporary critique of it is that it is distorting expectations about sex—some critics have even gone so far as to declare online porn a “public health crisis.” The adult entertainment industry has responded to the charge by initiating its own sex-ed modules. xHamster, for example, offers a sex education series called “The Box,” and Pornhub has launched a “Sexual Wellness Center” portal.

Sextech ventures, for their part, are challenging the adult entertainment industry’s de facto monopoly on sex education—but they insist on distinguishing themselves from porn. One of the ways they do this is by brandishing data: sextech sites sport diagrams, graphs, and charts to lend their activities a semblance of scientific legitimacy. OMGYes’s “Orbiting” episode, for example, presents multiple infographics and identifies dozens of ways to circle—“tight orbits,” “searching with circles,” “off-center,” “occasional direct swipe,” “accenting on the clock,” “inward on the borders,” “tall ovals,” “widening ovals,” “soft-hard figure 8,” and so on—along with a grid breaking down the preferences of women in a study led by Indiana University sex researcher Debby Herbenick.

By showing off scientific data and credentials, sextech tries to position itself in the health and wellness industry—while striving to make its offerings sexier than the typical sex-ed curriculum. Offline, OMGYes’s Rob Perkins refers to its offerings as “tutorials,” but the site itself uses the language of pop-culture television and podcasts: “seasons” and “episodes.” Herbenick makes a couple of cameos in videos buried in OMGYes’s “Research” section, but its foregrounded voices belong to the “everyday” women themselves, who speak from the same tentative place of curiosity and exploration that the company is trying to model for its users. There’s just enough science to provide credibility, but not too much to be oppressive: OMGYes aims for approachability above all.

Reform or Revolution

While OMGYes might seem to be selling Cosmo-style secrets of sex or groundbreaking data-driven discoveries about female anatomy, its main takeaways are actually quite simple. Women and their partners should get to know their bodies and learn how to communicate, verbally and physically, about desire. Communication doesn’t just mean talking, however, but figuring out what words mean: the OMGYes team told me that the first big discovery in their interviews with women was that “that feels good” means “don’t stop or change.” A pretty basic insight. “If there’s a ‘Jedi skill’ in the bedroom,” the OMGYes site reminds us, “it’s this ability to give and read feedback in real-time to constantly adjust and hone in on what feels best.”

OMGYes is not the only sextech company making the unsurprising assertion that good communication skills are important in sex. It’s also the premise of PlsPlsMe (“Among all the findings, we found out that 1 out of 3 Americans wish it was easier to communicate their sexual desires, and more than 50% of adults wished society was more open to sexual exploration”) and Cindy Gallop’s MakeLoveNotPorn.tv (“It’s all about communication.”)

This emphasis on communication comes straight out of second-wave feminism. In fact, most of sextech’s insights about female pleasure date back to the feminist explorers of sexuality in the 1970s. Second-wave feminists promoted “body education” by encouraging women to discover their anatomy through mirrors, masturbation, and grassroots information about arousal, birth control, and reproductive rights. They also urged women to discuss both their negative and positive feelings about their bodies and their sexuality. Our Bodies, Ourselves epitomized this approach. It originated as a pamphlet, “Women and Their Bodies,” published in 1970—when abortion was still illegal in the United States—that blamed society for estranging women from their sexuality. Dropping some Herbert Marcuse on their readers, the Boston Collective authors assert:

Society has caused the alienation of a woman from her body… Our sexual experience is so privatized that we never find out that other women have the same problems we do. We come to accept not having orgasms as our natural condition. We remain ignorant about our own sexuality and chalk it up to our own inadequacies.

While sextech ventures use snappier and less earnest language, they are working with the same legacy. As Ann Friedman observed in New York Magazine, “OMGYes is not a huge departure from the work of pioneering feminist sexologists like Betty Dodson”—only “the interface is more modern, the packaging more slick.”

So in stroking virtual vulvas, am I an orgasm warrior storming the barricades under the banner of the sextech revolution? Is sextech a resurgence of feminism through “disrupting” orgasms?

Not exactly. The modern interface and shrewd packaging aren’t the only differences between sextech and second-wave feminism—the politics are different too. Second-wave feminists didn’t just rage against women’s alienation from their bodies, they also clearly identified the culprits: capitalism, patriarchy, and the American legal and medical establishments.

Sextech, by contrast, steers clear of this radical message. Some sextech looks radical, but it essentially rephrases watered-down feminist insights for a general audience, and musters new data in order to teach old-fashioned communication skills. At its best, sextech treats women’s sexuality not as a pathology requiring medication (e.g., the dismal “female Viagra” that hit the American market in 2015), but rather as a product of cultural conditioning and education. But sextech remains deeply individualist—it styles itself as neoliberal self-help rather than as an instrument of social transformation. And its ambitions are modest: OMGYes and other platforms aim at incremental sexual reform versus sexual revolution.

As a counterpoint, it’s useful to consider one of the pioneers of sextech, and sexual revolution: Wilhelm Reich. Reich’s visionary, utopian, and at moments utterly barmy schemes were predicated on Marxist politics. Reich preached the power of sex and libido as a source of “bioenergy” in his work The Function of the Orgasm: Sex-Economic Problems of Biological Energy (1927). His Sexual Revolution (1936) made the case that political-economic formations, whether authoritarian or capitalist, relied on sexual repression to keep people in line. The patriarchal family structure “dammed up” libidinal energy as a means of social control.

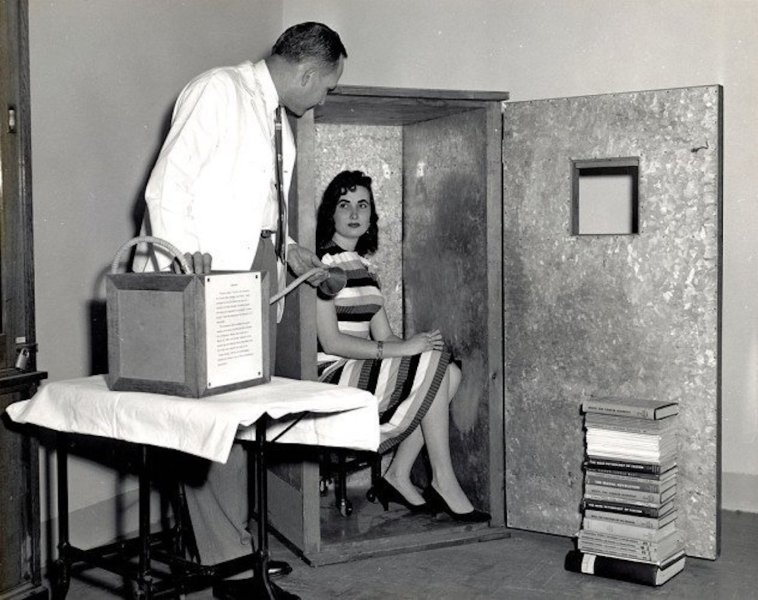

Reich saw this orgasmic or “orgone” energy as a potentially revolutionary force. He consequently devised the “orgone energy accumulator” box, which was supposed to increase biopower, “potency,” and cure physical and psychological illness. The design of the orgone accumulator was crude: Reich’s blueprints call for the construction of a large pine box—a “collapsible cabinet”—lined with layers of steel and glass wool. While William S. Burroughs claimed to have experienced a spontaneous orgasm while in his orgone box, Reich expected its effects to be more mundane. He instructed users to do “daily, regular sittings” in the box for limited periods of time as sensations of warmth flowed through them—a bit like a charging station for an electric car.

The orgone accumulator is laughable from an engineering point of view, but it was immense in its ambitions. If sextech ventures like OMGYes take a reformist approach, hoping to educate people about sexuality to produce better sexual outcomes, Reich called for full-scale revolution, using sexual energy to destroy capitalism. His endgame wasn’t merely the hedonistic pursuit of individual pleasure, but the dismantling of the entire traditional Western family structure, the patriarchal social order, and the conditions of capitalist production.

Sextech, like porn, monetizes the orgasm. For Reich, however, the orgasm wasn’t a commodity—it was a weapon. It held the power to demolish the old world and build a new one in its place. It promised not only sexual liberation, but the liberation of humanity as a whole.

Sextech doesn’t begin to approach the utopian intensity of Reichian revolution. But in the age of Trump, sexual reformism might be the best we can get. To give OMGYes and its sextech peers the benefit of the doubt, they are drawing attention to the pressing need for new modes of sex education. This is important work, especially as we enter a regressive political moment when the technologies and social movements that made sex for pleasure possible are under threat.

Legalized abortion is at the top of Trump’s hit list. Non-discriminatory policies protecting LGTBQ people are also vulnerable. If sextech raises its ambitions to not only help users overcome the barriers to their bliss, but also get them to think about the conditions that created those barriers in the first place, and have a stake in perpetuating them, it may start to fulfill the promises in its mission statements. Then sextech’s “pleasure education” might live up to that very second-wave feminist slogan, the personal is political.