Marina Kittaka is a multidisciplinary artist based in the Twin Cities, working mainly in video games with her creative partner Melos Han Tani as indie game studio Analgesic Productions. They’ve worked together for over a decade making surreal adventure games with a particular blend of analysis, music, and art creating a strong atmosphere. Marina is also the author of the 2020 essay “Divest from the Video Games Industry.”

We spoke with Marina about disrupting the cultural dominance of AAA games, how specific tools can shape creative subcultures, and how research into animal weaponry is shaping Analgesic’s newest game, Angeline Era.

Claire Zuo: How did you get into video game development initially?

Marina Kittaka: When I first got access to the Internet, my older brother and I were always into video games and were always trying to find more and more games. And since we could only buy a mainstream game every once in a while, we found that there were these free games on the Internet. And a lot of the time they were tied to hobbyist developer communities and game making engines. If you wanted more games, you just played ones that other people were making themselves.

In terms of a professional outlet, that really came together when I was put in contact with Melos by a mutual friend. We worked on our first game Anodyne mainly for fun, thinking we might get a little ad revenue, but we got lucky and it did surprisingly well – so we were able to continue making games from there.

Claire: You mentioned growing up and playing a lot of mainstream games because that was what it was accessible to you, but also discovering this world of more DIY and hobbyist game makers online. How do you understand your own work as a game dev or relation to those experiences?

Marina: Over the course of my life, games, even games that would more or less be considered AAA have changed so much. The degree of technological shift is so extreme; something that Melos and I think about is how one of our favorite games as kids that was influential to us was Legend of Zelda: Link's Awakening. That game, and a lot of Gameboy games, had relatively small teams in ways that could be comparable to what we might consider an indie game now.

In terms of how we situate ourselves, it's really hard for me to have that perspective on my own work. I rarely see another game and think, Oh, that's working in the same scale or the same realm as my work. I definitely do know a lot of game creators who are doing interesting things, but most are not getting a lot of money for that. Then there are other indie studios who have been putting out games for a longer time, but they often read to my perception as more official, more business-like.

Claire: Another question I have is around making this kind of work sustainable for oneself financially, as most people who I know who make small games are doing it for free, or for a few dollars here and there. What is your experience with getting the time and resources to make these games and live your life?

Marina: I've had part time service jobs for stretches of several months a couple of times over the past decade or so; there's definitely a pressure there. We've been able to get this far and not have to have a lot of other jobs by releasing fairly frequently, and just keeping our budgets very low. We haven't really been able to contract out, have external studio space or anything along those lines. We both have support structures, in terms of family and friends, who contribute in large and small ways. More recently we've been turning towards looking for some outside funding, and we've gotten grants occasionally, including from the Game Devs of Color Expo.

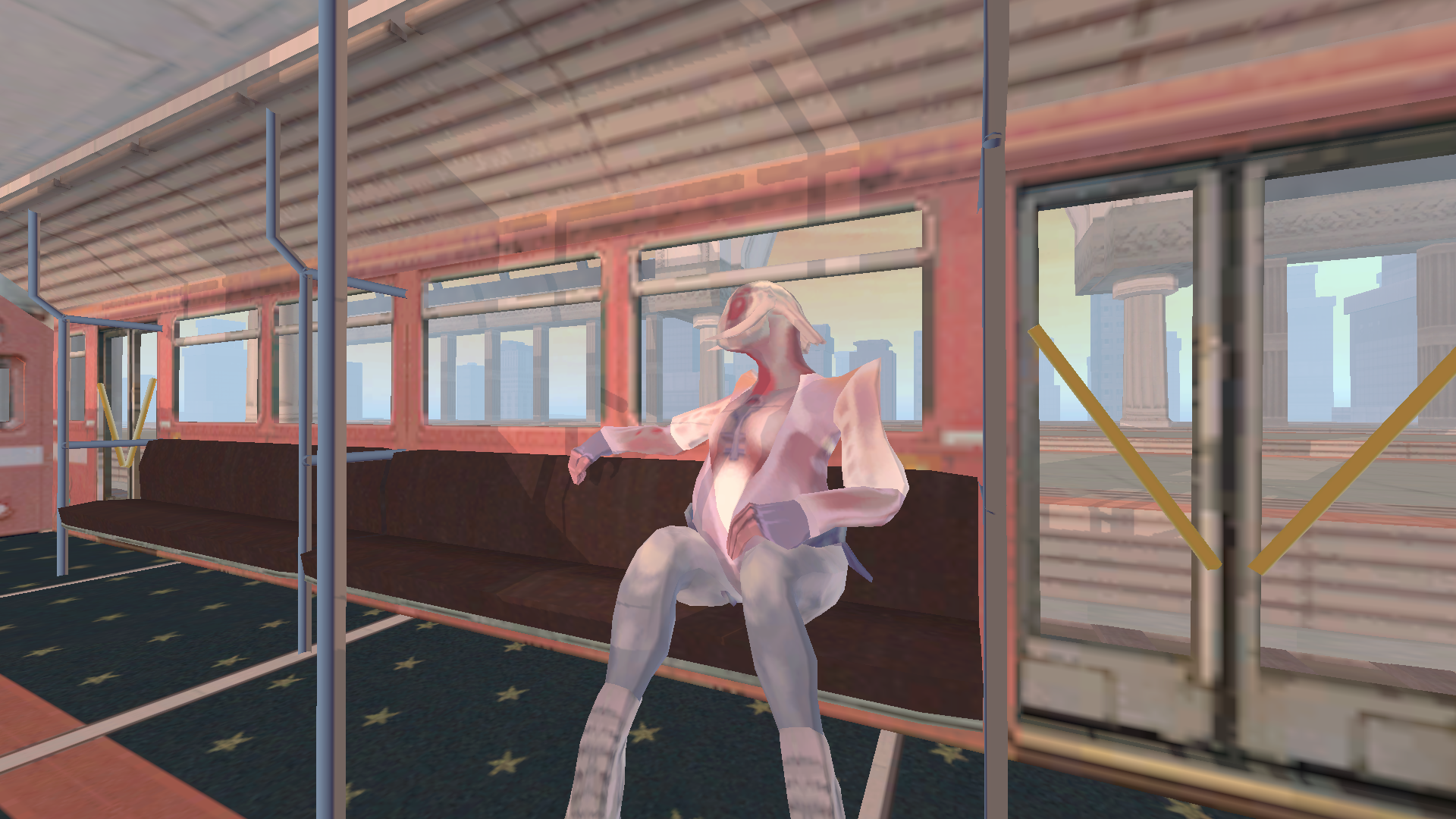

Screenshot from Sephonie.

Claire: What does your “tech stack” look like? Both high and low tech, what tools do you use to make your games and your art more broadly?

Marina: I spend most of my time in Photoshop and Blender, and writing documents in Google Docs. We're using Unity for our current game and our past few games. I've also been using Blast FX, which is a program to make particle effects.

Claire: Are there any other tools that you want to shout out?

Marina: Let me look at itch.io real quick. I think Electric Zine Maker is a really cool tool! And there’s this site, kool.tools by this creator named Candle. Candle makes a lot of little tools and also has done a lot of Bitsy* community related stuff. Using older software is also interesting. I've been seeing some people using Bryce3D lately.

Claire: What is that?

Marina: It's an old 3D rendering software, used to make what you think of when you think of the computer-generated nineties rave posters or the Trapper Keeper aesthetic. It's definitely interesting when people use older software. So much of 3D art in games is deciding how much and where to fake information. There are so many different places to decide what happens when. I love to think about how the tools that exist can spawn whole subcultures, can be so tied into the life of subcultures and how they interact.

Claire: Yes! These days, are you very much of a gamer yourself? And how has making games full time changed your relationship to playing video games and to other forms of play?

Marina: I definitely don't play games as much these days. Part of it is struggling to find stuff that I'm interested in. And part of it is that gaming overlaps with the activities that would cause or worsen repetitive strain injuries. I just need to do anything else besides computer or controller type stuff. So I have been more into reading and movies and going for walks and swimming!

I would like to have maybe a more healthy relationship with playing games. Sometimes I get into a game and then play it a little too much and it kind of consumes my mind. And then I go back to not playing games for a while.

Claire: Yeah, that's so real, both with getting consumed and with regard to the physical toll of being a game dev and being on the computer a lot. Are there any influences from books, or other non-game media, that have been really important to your games?

Marina: We announced our next game recently, Angeline Era, which I've been doing a lot of research for. This next game is set in this alternate history of the 1950s, and the main character is a Japanese-American of my grandparents’ generation, who were Nisei. This character goes to an Ireland-inspired fantasy land, and there's these conflicts between these different kinds of ways of idealizing a potential past versus a potential future. And so I've been doing research recently about early Christianity and the apocrypha, and also Japanese-American history. A lot of it won’t get fully expressed in the game, because the story will be in some ways a bit minimalist, but hopefully there's a certain kind of richness there.

One book I've been reading, Animal Weapons by Douglas Emlen, has been really shaping my thinking. It's about big animal weapons, like horns and claws and fangs – the circumstances under which those develop - and he relates that a little bit to human arms races. I don't really get the vibe necessarily that I would be on the same page with this guy politically, but it has been shaping my thinking on some issues. For example, if there is some resource that can be defended, that leads to sort of like a classically “fair fight,” or one on one duel between two creatures and the winner will get to reproduce or something along those lines, then that can set off an arms race where their weapon just keeps getting bigger and bigger and bigger and they keep devoting more of their body's energy resources to that at the expense of like other things. Something that can cause the arms race to end is either just getting so big that they can no longer just be alive, do the rest of their bodily functions, or a chaotic fight when there's a lot of different creatures involved in a free-for-all. Then it's no longer a fair fight between two and then the fight can go in a lot of different ways.

Or what this author calls “cheats and sneaks.” So there are these tunnels that dung beetles can defend against other beetles coming in to mate with their dung beetle mate. But sometimes small dung beetles that could never win a fight tunnel in from the side and sneak in and mate and try to run away really quickly.

There's a lot of ways that I've been thinking about this, both in terms of the themes of Angeline Era and then in terms of the games industry and how when you do make a game for cheap that people like, that is this kind of existential threat to the fundamental terms of the arms race. There's a very clear technological arms race with the games industry–there are huge, big budget projects that are really clunky and slow, but can still succeed within a sort of “fair fight” mentality. That arms race is still alive and well, though it seems to be maybe at a tipping point currently.

Although it's not the same as the evolutionary biological model of creatures, you see how it could present this existential threat to the whole idea of what the really big budget games are doing fundamentally, and that if that were ever allowed to go too far, that it would potentially break apart the whole incentive structures of the system. I was reflecting on why the big games sites had a brief wave of covering random indie games around 2012, but then it felt like there was a lockdown where they just stopped and only covered them if it's something that has already gotten really huge and become a kind of exception proving the rule.

Screenshot from Angeline Era, forthcoming.

Claire: Right. Can you say a bit more about how a game that doesn't really follow those technological rules becoming really popular would threaten the incentives of the video game industry, especially for people who haven't really thought about what those incentives even are?

Marina: Yeah! There's been this rapid growth over the relatively brief existence of a video games industry. And a lot of that relates to this braiding together of the artistic possibilities of what video games can be with the idea that games, and everything that you can experience, just get better and better the more advanced the technology is.

People are banking on this narrative that allows a lot of money to flow into the industry and to create more and more expensive games with more and more complicated rendering techniques. To relate it back to the animal weapons arms race, because the games that are expensive have these big budgets, they're able to spend inordinately on marketing as well, and they're able to dominate the conversation. That further encourages this feedback loop where having the biggest budget, spending the most money, and ostentatiously appearing as the most expensive thing can allow you to continue to be the most expensive thing and to make the most money.

When we take a step back, we can see that as humans, as players of games, that there are all kinds of different reasons why we might be interested in playing a game and that none of those actually have to do with how many polygons there are. It can be jarring if we're so used to the narrative of, of course everything is just going to be better and better the bigger and more expensive it is. Then you can start to realize and notice that like, oh, like I could just make something myself, or I could just play something that some random person made and I might have a really meaningful experience with that.

And if enough people realized that, then it would disincentivize the whole structure, where it would no longer be guaranteed that spending the most money would actually lead to the best outcome commercially. That's why I do think that there's more of an incentive than one might realize in the abstract for the broadness of games to be recognized in the general public. That's why I feel dissatisfied with the rhetoric that, We can have both! The biggest Call of Duty game can coexist with all these random indie games... The huge amounts of money that flow, that all could fundamentally change if the perception of the industry from the audience changed. And so the indie games, everything else besides the biggest AAA games, have to be narratively kept in their place as a small side thing.

Claire: Thank you! That was a really good summary for people who are newer to these ideas and to indie video games. A lot of the Analgesic games are aimed at being accessible and not alienating people on a “skill” level while also being really complex narratively and thematically. Often they follow an arc of following contradictions or dissonances until the normative regime of the game unravels, like in Anodyne 2, for example, and thinking about how queer relation and care lead to a lot of those new revelations or discoveries or imaginings. And your games also really take up questions of ecology and more mutual or reciprocal human relations with non-human life. Who do you see your games being for?

Marina: Beyond what is obvious about climate change and in terms of capitalism and the arms race of corporations being a destructive force for, you know, the long-term health of humanity and other living things and the Earth in general… When I do think about ecological themes in my work, a lot of the time it is a metaphor, and not in the sense that the reality of the ecology is irrelevant. But there’s some resonance between how we think about and manage our personal relationships and humanity's relationship to the earth and the mysterious ways that those things are tied into each other - that just feels like the baseline space to begin asking questions.

On an active level, I don't really picture an audience while I'm working. But when I see certain work that embodies an unexpected confidence or where the creator seems kind of mad with power, even though they don't have institutional power, they're just making something and building out the entire logic of its mechanical worlds... I feel awakened on some level. And I do hope that other people who are interested in being creative experience that with my work as well.

Something I've written about is how it's easy to make this false dichotomy between professional, snobby, over-specialized, and corporate on the one hand, and then outsider, raw, approachable, and populist on the other. Critical frameworks for understanding what's good about outsider works are relatively underdeveloped. There are ghosts of understanding when I play certain work that inspires me. But my critical apparatus for understanding what makes it good is underdeveloped. And that's a very fruitful place to be.

When I make work, I do get a little stuck sometimes. Looking at the tutorials, what is easiest to find will normalize you into the ways of determining quality that are most mainstream. It's a constant internal struggle that I have as an artist to be like, how do you get better without becoming in some ways worse? Just because the ways that we understand getting better are boring to me, but also, not always boring. It's complicated.

Claire: Definitely. On that note, are there any indie games or makers that you want to shout out?

Marina: Yes! There's a game I like called Cataphract OI by Sraeka-Lillian. Cataphract OI is part of a series of experimental RPGs and Sraeka is someone who thinks very deeply about the details of why classical JRPGs work. And then because of that depth of thought is able to do things that are very specific and very interesting. I really appreciate it when people—whenever anyone's kind of thinking very closely and deeply about something that is sort of oddly specific to them.

Some books that were really influential on my games are The Race Card: From Gaming Technologies to Model Minorities by Tara Fickle, and Open World Empire: Race, Erotics, and the Global Rise of Video Games by Chris Patterson. Those books are doing really interesting work at the intersection of Asian-American and game studies. And I am really looking forward to this game by Chris [Patterson], also known as Kawika Guillermo, that is a visual novel adaptation of his novel Stamped: an anti-travel novel.