The knock on the door came at 2:00 a.m.… The woman sat at my dining room table asking me a thousand questions, and the man wandered around, wordlessly inspecting my house… For the next forty-five to sixty days, the agency would investigate whether there was credible evidence that I was a neglectful or abusive parent… They insisted on completing the most dreaded aspect of an investigation: waking up the kids for strip searches to check them for bruises. I marched each of them out one at a time into the bathroom, where they had to remove all of their clothes down to their underwear, including the baby… As for the allegation of child abuse, I eventually beat the case and received a letter from the New York Statewide Central Register of Child Abuse and Maltreatment saying that the allegation was unsubstantiated. There’s no innocence in family policing—only “We could prove you’re abusive,” or “We couldn’t prove you’re abusive.”1

—J. Khadijah Abdurahman, scholar and parent

I. Context of AFST Deployment

A. Child welfare as family regulation

Each year, more than three million US children are subjected to investigations by state and local child welfare agencies, the majority of which are closed without a finding of maltreatment.2 Most investigations result from allegations of “neglect,” a broad category, distinct from physical or sexual abuse, expansive enough to justify government oversight of families experiencing poverty or those whose parenting practices do not constitute abuse, but are unfamiliar or frowned upon by caseworkers or agencies.3 Families describe these investigations as frightening, invasive, stigmatizing, and rife with bias.4 Given the intrusive nature of child welfare interventions and the questionable benefit to impacted families and children, as detailed below, the terms “family regulation system” or “family policing system” are increasingly used to replace a moniker that encourages a view of the system as a neutral and benevolent protector.

While local investigation procedures and evidentiary thresholds vary, US child welfare law and practice is broadly structured around a paradigm of parental fault.5 Caseworkers are tasked with “support[ing] the same parents they are charged with investigating and prosecuting,”6 giving them contradictory mandates—both to refer parents and families to services, and to gather any information that could be marshaled as evidence of parental unfitness.7 Every interaction with the family regulation welfare system thus carries the possibility of disruption by government authorities—a threat that marginalized families, whom the family regulation system disproportionately targets, feel most acutely.

Meanwhile, the reach of this surveillance is extensive. By some estimates, over one-third of all US children are involved in a protective services investigation by the time they turn eighteen.8 It is also stunningly uneven. More than half of Black children experience an investigation in the same time frame, nearly double the rate for white children.9 And Indigenous children, Latinx children, and those from families experiencing poverty are also disproportionately subject to investigations and placement in foster care.10 While these interventions are theoretically supposed to protect children, empirical studies show that the trauma of investigation and family separation can have long-lasting effects. Additionally, young people with histories of welfare system involvement have lower rates of educational attainment,11 decreased access to mental health services with a concomitant increased incidence of mental health needs,12 and a disproportionately greater risk of future incarceration.13

The operation and impact of Pennsylvania’s child welfare administration is largely consistent with these nationwide realities. In Allegheny County, the Department of Human Services (DHS) Office of Children, Youth, and Families (CYF) purports to provide “preventive, protection, and supportive services to work with children and families, with emphasis on family preservation” and “direct services through caseworkers, case aides, and a network of contracted agencies.”14

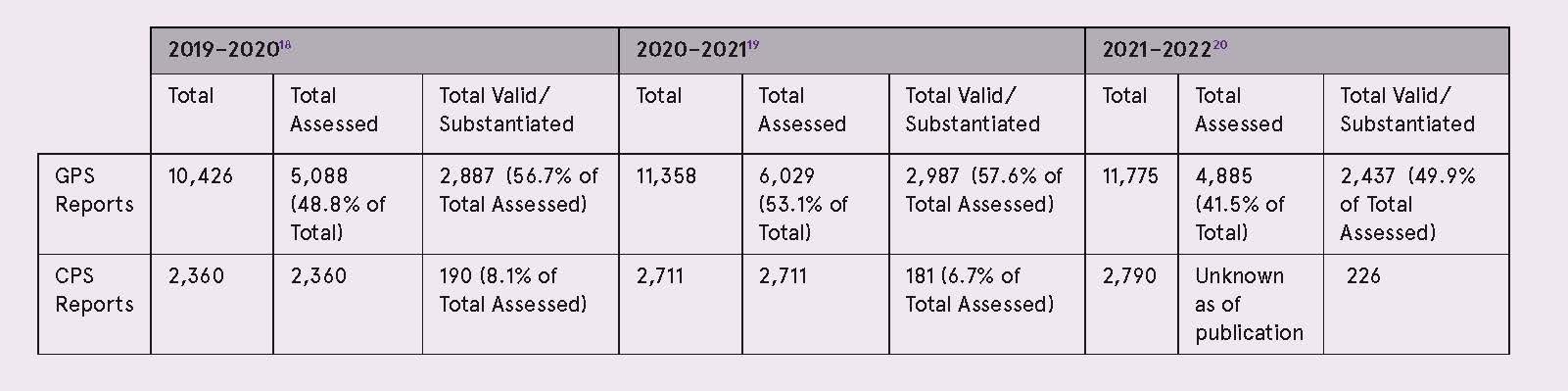

Both across the state and in Allegheny County, the majority of child welfare investigations and substantiations involve allegations of neglect, which in Pennsylvania are called General Protective Service reports. Regulations define GPS reports to include the sweeping category of situations where a child “is without proper parental care or control, subsistence, education as required by law, or other care or control necessary for his physical, mental, or emotional health, or morals.”15 Allegations of physical or sexual abuse are called child protective service (CPS) referrals.16 GPS reports have historically represented approximately 80 percent of allegations received by family regulation agencies across the state and been the majority of reports found to be valid.17 Allegheny County’s distribution of reports received, types of reports, and validation rate is consistent with the state’s overall trends. For instance, Pennsylvania’s state DHS reported the following for 2019–2022181920:

Among the GPS reports the County deemed valid in this period, the most commonly found concerns were (1) caregiver substance use, (2) child’s behavioral health / intellectual disability concerns, (3) conduct by caregiver that places child at risk or fails to protect child, (4) experiencing homelessness/inadequate housing, and (5) truancy / educational neglect.21

Pennsylvania’s child welfare system is also marked by racial disproportionality and disparities from intake to disposition, as was recently acknowledged by the state DHS in its 2021 Racial Equity Report. Black children constitute 14 percent of the state’s total child population but make up 21 percent of children named in maltreatment allegations and 35 percent of the state’s foster care population.22 And, as DHS acknowledged in this report, “given the trauma that children can experience when separated from their families and the impact such trauma can have on social, economic and health outcomes, racial disparities in placement rates can have long lasting effects that are detrimental to the well-being of Black children and their families.”23

B. Legal authority and limits on family regulation by the state

As a legal matter, the state can act to protect the health and well-being of children based on its inherent police powers and parens patriae authority.24 At the same time, parents have a constitutionally protected interest in the “companionship, care, custody, and management” of their children, as the US Supreme Court has repeatedly acknowledged.25 The Court has also held that parents and children have a shared constitutionally recognized interest in family preservation that “does not evaporate simply because [the parents] have not been model parents or have lost temporary custody of their child to the State.”26 Notwithstanding this body of law and the related constitutional right to the “integrity of the family unit,”27 the family regulation system suffers from a dearth of due process protections—that is, constitutionally mandated procedures intended to prevent state overreach—and adequate mechanisms to ensure parents and children are aware of and able to meaningfully assert their rights.28

By way of example, criminal law enforcement’s ability to enter a home and question, search, or detain people is at least formally circumscribed by constitutional limits.29 Comparable protections limiting child welfare caseworkers’ ability to question, search, or detain parents or children are scant,30 not clearly established,31 or routinely flouted and underenforced,32 even though child welfare investigations can result in loss of a parent’s fundamental right to make educational or medical decisions, temporary or permanent family separation, and even criminal charges.33 Similarly, although almost every federal court of appeals to decide the issue has held that the Fourth Amendment requires child welfare agents to have either probable cause or judicial authorization to enter a home in the absence of consent,34 a host of factors have made this constitutional right an inadequate restraint on child welfare investigations. Parents often do not know of these rights, and all but a handful of states impose no obligation whatsoever to inform parents of their existence. What’s more, any state-law right-to-counsel guarantee typically attaches well after the initial entry and investigation.35 Even for parents equipped with this knowledge, invoking their and their families’ rights can be a double-edged sword: while it may delay or avoid an unwarranted search, refusal to cooperate with family police can be, and routinely is, cited as an additional basis for agency intervention.36 Moreover, if the parents or their counsel convince a court that a home entry was unconstitutional, the agent’s observations from the search are still admissible in court. The lack of a meaningful remedy disincentivizes families from contesting unlawful entry and family regulation agents from following these legal requirements.37

This appears to be the case also in Pennsylvania, whose high court in 2021 issued an extraordinary ruling that not only required probable cause for child welfare investigators to obtain a home-entry order, but further set specific evidentiary and procedural requirements for the issuance of such orders.38 While it is exceedingly difficult to assess child welfare investigators’ on-the-ground compliance with this new rule, without reliable knowledge of their and their families’ rights, access to early-stage representation, or a reliable means to challenge unlawful home entries after the fact, parents face tall barriers to vindicating rights even under Pennsylvania’s more protective regime.

Thus, parents facing investigation might (and often do) feel obligated to open their homes for search, offer up sensitive medical information, or make their children available for traumatizing “body checks” by state agents.39 A family may acquiesce to “strict behavioral compliance requirements” as a condition of remaining in each other’s care,40 or even burdensome “‘safety’ plans” that separate children from their parents without any formal process, judicial oversight, or independent determination of parental unfitness.41

C. Impact of system involvement on families and children

The state’s justification for this system is to promote the safety and well-being of children. Yet every step—from the moment of initial contact with a caseworker to removal from the family and entry into foster care—poses the risk of serious emotional, psychological, and physical harm to parents and children.

In 2022, a joint report of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and Human Rights Watch found that parents across the country had similar experiences of child welfare involvement, notwithstanding differences in child welfare practice from one jurisdiction to the next. Investigations and monitoring of a family’s conduct, which take place even if no child is removed, were like “ ‘living under a microscope,’ and a parent’s appearance, mannerisms, or tone of voice could be used against them in a child welfare report.”42 The ubiquitous presence of mandated child welfare reporters at agencies that provide services for families in need—from educational programs to government benefits,43 mental health or medical care to safety services44—undermined their trust in and undermined their willingness to engage with these providers. Parents felt they were presumed “guilty before proven innocent”45 and “under constant surveillance.”46 A study conducted to find out how affected communities in Allegheny County felt about the introduction of an algorithmic decision-making tool in the County’s child welfare practice showed the same distrust exists among parents involved in the County’s child welfare system:

Families often referred to negative experiences in their own lives, and reflected on the oppositional nature of the system, saying, for instance, “It’s been me versus the system.” Most family participants had low perceptions of trust in the decisions made, and low expectations of the benefits that the system could provide.47

Investigations also constitute a significant invasion into children’s privacy and bodily integrity, and disturb relationships that otherwise provide a crucial source of stability, especially for young children.48 Isolating children from their caregivers to be questioned and searched, whether at school or at home, can shake young people’s sense that their environment is reliable and safe, and impart a sense of stigma.49 One California mother described the impact on her children as follows:

[My children] already have to deal with this [investigation] at home, and the school may have been the only safe space for my child. But the minute the social workers go there, they take that away from them. There is a level of shame that they start to carry, that [their] parents are going through this. They have to tell their friends: “That’s my social worker”… It makes [my children] very uncomfortable and like they are being looked at differently.50

Beyond investigation, the short-term or permanent removal of a child from their family also leaves a lasting mark. In the words of the American Association of Pediatrics, family separation “can cause irreparable harm, disrupting a child’s brain architecture and affecting his or her short- and long-term health. This type of prolonged exposure to serious stress—known as toxic stress—can carry lifelong consequences.”51 This is true even of the brief separations that abound in the family regulation system,52 where case agents are uniquely empowered to remove children from their homes on an emergency basis without judicial authorization. A child entering the foster system may be separated not only from parents but from siblings, other relatives and caregivers, their school environment, and their broader community; and they may experience this loss many times over as they are transferred from one setting to another in a phenomenon known as “foster care drift.” Further, the uncertainty inherent in a family regulation investigation is itself deeply destabilizing and interferes with young people’s ability to form healthy attachments throughout their lives.53

Placement in foster care also raises the risks of physical harm to children. As countless news reports document, and studies bear out, children in the foster system are especially susceptible to maltreatment.54 One study of residential child welfare facilities in Pennsylvania’s foster system found that children in such facilities are subject to a “pattern of: physical, verbal, and sexual abuse … by staff; lack of supervision by staff leading to child-on-child physical and sexual assaults; and inappropriate use of restraints, all of which place children at grave risk of harm.”55 Notably, the family regulation system’s perception of analogous risks often forms the basis for separating families in the first instance.

Research demonstrates dramatically higher incidence of mental health challenges like depression and post-traumatic stress disorder among young people in the foster system than in the general population.56 Some studies have found that the rate of PTSD in foster children nearly doubles that experienced by war veterans.57 Meanwhile, mental health services remain under-accessed, and children in foster care are instead subjected to unnecessary and/or overuse of psychotropic medication instead.58 This follows the pattern of physical health outcomes for children in the foster system, which research shows is routinely ignored and untreated.59 According to one report by the American Academy of Pediatrics, “Children and adolescents in foster care have a higher prevalence of physical, developmental, dental, and behavioral health conditions than any other group of children. Typically, these health conditions are chronic, under-identified, and undertreated.”60

Despite the empirical and qualitative research documenting the harms of separating families, as of 2019, only two jurisdictions—Washington, DC, and New York State—require courts to consider the harm removal might cause a child when making decisions about child placement.61 Elsewhere, the two principal questions that courts must ask is whether the state made “reasonable efforts” to prevent removal, as required by federal law, and whether the child faces sufficient risk of harm in the absence of removal to justify separating them from their family.62 To the extent some states’ laws also require courts to consider the “best interests of the child” and states do not prohibit courts from weighing the risks of harm from separation and/or foster care placement, without an affirmative mandate to do so and without clear direction how those risks should be factored, courts are free to ignore or downplay such evidence. Thus, as scholar Shanta Trivedi has pointed out, “a judge could easily find that moving to a foster home in a better neighborhood with wealthier foster parents is in a child’s best interest, even if significant harm-of-removal evidence is adduced.”63

D. The design and purpose of the Allegheny Family Screening Tool

Against this backdrop, in August 2016, the Allegheny County Department of Human Services (hereafter, “Allegheny County”) launched what has quite possibly become the most prominent predictive analytics tool in the US child welfare system: the Allegheny Family Screening Tool (AFST). The agency first issued a call for proposals in 2014 to design a system that would “(1) improve the ability to make efficient and consistent data-driven service decisions based on County records, (2) ensure public sector resources were being equitably directed to the County’s most vulnerable clients, and (3) promote improvements in the overall health, safety and well-being of County residents.”64

The winning proposal involved the creation of an algorithmic tool, the AFST, which promised to allow “large populations to be easily and cost effectively screened” and argued that “computer-generated algorithms” would provide the basis for a “far more reliable measure of success or failure than the intuitions and anecdotal evidence of frontline staff by themselves.”65 Essentially, the AFST would cull County records for data about people who had been investigated by its child welfare agency, the CYF, and identify those data points (known as “features” or “variables”) that correlated with cases in which the County eventually removed a child.

The AFST is used only in the context of GPS reports, not those designated as alleging abuse or severe neglect. State law requires local child welfare agencies to investigate reports in this latter category, which in Pennsylvania are called CPS referrals.66 Line-level screening staff retain discretion over how local child welfare agencies respond to referrals designated as GPS.67

With the introduction of the AFST, a GPS referral may be:

1) screened out (i.e., closed) upon receipt;

2) forwarded for a field screen68 (i.e., a “home visit”) to determine whether a full investigation is warranted; or

3) immediately screened in, thereby launching a full investigation.

Figure 1. The screening process in Allegheny County.

Upon implementation, call screening workers would enter information about the allegations and people involved in a GPS referral. The AFST would then estimate the likelihood that the referral would result in forcible family separation by the state within two years if it were to be screened in, based on whether and how the historically identified data points also appeared in the intake. As currently used, the AFST expresses this estimation as a “risk” score between one (lowest relative risk) and twenty (highest relative risk), where risk represents the likelihood that the County will remove a child from their home within two years of the referral.69 Where there is more than one child in a referral household, the AFST calculates risk scores for every child. But, even though the AFST generates estimations at the individual child level, call screeners see only one output: either the maximum numeric score across all children in the household, or a single risk label (e.g., “high risk”) that is determined in part by the maximum score of all children on the referral.70 Call screeners are encouraged to consider the AFST’s output as one factor in the decision whether to investigate a maltreatment allegation or close it at intake.

Under Version 2 of the AFST, implemented in November 2018, if the maximum score on a referral fell between eighteen and twenty and any child on the referral was aged sixteen years or younger, a “high-risk protocol” required that the referral be screened in unless a supervisor permits, and explains in writing, the decision to forgo an investigation.71 A separate “low-risk protocol”—not present in the AFST’s first version—was implemented in November 2018. This protocol initially applied if the maximum score on a referral was between one and ten and all children associated with the referral were at least twelve years old. Pursuant to this policy, workers were shown only a “low risk” label and were recommended, but not required, to screen out the report.72 The County and tool designers adjusted the low-risk protocol in October 2019 (Version 2.1) to apply if the maximum score on a referral was between one and twelve and all children were at least seven years old.73 With both high- and low-risk protocols, call screeners see not a numerical score but a color gradient bar with a label corresponding to the relevant protocol. According to the 2019 Methodology Report describing Version 2 of the AFST, 24 percent of referrals triggered the “high-risk” protocol, 4 percent triggered the “low-risk” protocol, and 72 percent fell into neither—that is, screeners saw numeric scores for 72 percent of referrals.

The AFST has so far gone through four updates. Version 1 was used from August 2016 through November 2018; Version 2 was in use from November 2018 to July 2019, at which time the County implemented some data-source changes and made adjustments to the back-end model (Version 2.1); in April 2022, a fourth version was implemented after adjustments were made to the back-end model and a new data infrastructure was created. In June 2021, Allegheny County provided the ACLU and the Human Rights Data Analysis Group (HRDAG) with the training materials used by call screening workers, along with copies of the current code, training data, three months of data from the use of the tool in the spring of 2021, regular tool-performance quality-assurance reports, and feedback submitted by workers on specific AFST scores.

II. The Impossibility of Measuring the AFST’s “Accuracy”

A. A mismeasure of risk

In the child welfare context of the family regulation system, “risk” has a specific reference point: namely, the risk that a parent or caregiver ostensibly poses to a child. The AFST does not record this measure of risk directly, nor could it. Instead, the AFST’s outputs reflect the estimated probability that County agents will remove a child from their home—that is, the risk to child and family of state intervention and disruption.74 While the AFST training materials we reviewed took care to note that the tool only predicts likelihood of future placement, rather than likelihood of future maltreatment,75 this nuance seems to have been lost to some audiences. For example, a 2018 feature article in the New York Times about the AFST was titled “Can an Algorithm Tell When Kids Are in Danger?,” even though the algorithm does not predict future abuse or neglect. Further, the article erroneously described a referral with an AFST score of nineteen as a score “in the top 5 percent risk for future abuse and neglect.”76 What an AFST score of nineteen means, in fact, is that the estimated probability that the family will experience a separation within two years falls in the top 10 percent of probabilities in the data used to develop the model, which was based on referrals the agency received between 2010 and 2014.

The AFST’s creators acknowledge that “there are valid concerns that the AFST model, and other models trained to predict system outcomes like out-of-home placement, may be predicting the risk of institutionalized or system response rather than the true underlying risk of adverse events.”77 As even the county explains, “a challenge [of predictive modeling] is to identify outcomes to predict that are truly independent of the system and not too rare to be predicted.” With the AFST, the county views removal to be sufficiently independent from the system “[b]ecause placements are determined by a judge, and all parties (parents, children and County) are represented by attorneys, [making] a placement outcome reasonably independent of the County child welfare system.”78 But since the county can only lawfully place a child into the foster system after a court has become involved, the court is part of the “institutionalized or system response,” not detached from it.79 Researchers who observed and interviewed call screeners using the AFST found that even screeners and their supervisors disagreed with the use of child removal as a proxy for child abuse or neglect. Based on their experiences, “children were often placed in foster care without any concerns of child abuse or neglect.”80 Another caseworker suggested that a child might never enter the foster system even where legitimate concerns of child maltreatment do exist, indicating that, at least in some caseworkers’ view, removal may be both an over- and under-inclusive correlate to abuse or neglect.

The AFST developers also sought to confirm that the high-risk scores were correlated with child maltreatment by comparing (anonymized) hospital records of children who would have been assigned the highest and lowest AFST scores had the tool been in use for screened-in reports from 2010 to 2016. The developers looked specifically for any correlation between the risk score an individual child would have received, even where multiple children were in the home, and three categories of injuries that the hospital coded for—any-cause injury, suicide and self-inflicted injuries, and abusive injury. They found that children who would have received a score of twenty had a hospital visit subsequent to the referral for any-cause injuries at a rate of 14.5 per 100, while those within the one-to-ten range had such visits at a rate of 4.9 per 100. Based on their findings, the authors concluded that “the Allegheny model, trained to predict foster care placement, was sensitive to medical encounters for injuries.”81

While it may be true that the AFST is sensitive to medical encounters for injuries, there is a mismatch between “the Allegheny model” as analyzed here and the AFST as actually deployed during this time period. In this analysis of correlations with medical encounters, the tool’s developers examine individual risk scores and medical encounters, both at the child level. But the AFST does not present individual children’s risk scores to call screeners making screening decisions; rather, it presents a single score or label for all children on a referral based on the maximum score on that referral. While this distinction may seem insignificant at first glance, in another recent analysis, we found that this aggregation process shifts scores upward for everyone, and especially for Black families.82 In data from 2010-2014, roughly the same percentage (about 5 percent) of Black individuals and non-Black individuals receive a score of twenty when considering individual scores, as the medical encounter study did. But if we instead treat each person’s risk score as the maximum score of the referral they are on—as the AFST does in practice—roughly 5 percent of non-Black children receive a score of twenty, compared to 15 percent of Black children. But if we instead treat each person’s risk score as the maximum score of the referral they are on—as the AFST does in practice—roughly 5 percent of non-Black children receive a score of twenty, compared to 15 percent of Black children—suggesting the mismatch between the medical encounters study’s reliance on individual risk scores and the deployment of the AFST should be a consideration for interpreting the study’s results and their implications for assessing the AFST’s “accuracy.” This mismatch is especially significant in light of the additional finding in the medical encounters study that their results “showed a mixed picture with respect to the sensitivity of the risk score to different racial subpopulations.”83

B. A misrepresentation of risk

Although the AFST’s written materials do not claim that its scores represent absolute risk of removal, the shorthand reference to “risk” and the way in which scores are presented to call screeners likely overemphasize the scores’ significance. “Relative removal risk” would be a more precise and helpful label than “risk score” when describing the AFST’s outputs.

An AFST score does not reflect the absolute risk that a child identified in a referral will be removed. Instead, it reflects how the estimated probability of removal for that particular child compares to the probabilities reflected in the data used to develop the model. Put differently, an AFST score of twenty (the highest possible) means that the estimated probability of removal for the child falls within the range of the top 5 percent of probabilities found in the data used to develop the model. Whereas it might be most intuitive to interpret the highest possible AFST score as representing a high absolute probability of child removal, other analyses have highlighted that individuals who receive the highest possible risk score experience removal less than 50 percent of the time.84 This is consistent with our observation based on an analysis of data used in the model-development process, and, in particular, screened-in referrals from 2010–2014 for which information about removal within two years was available. As highlighted in figure 2, for referrals that would have been classified with an AFST score of twenty in that time period, 47 percent of such referrals resulted in a removal within two years. This is to say that even the referrals that the AFST identifies as posing the “highest risk” of removal are estimated to be more likely not to involve a child removal at all. Applying the assumption that appears to underly the AFST—namely, that child removal is a useful proxy for which cases involve a serious risk of neglect or abuse—it would seem the AFST flags as “high risk” cases that are estimated as quite unlikely to involve these concerns.

The decision to translate the AFST’s outputs as numeric scores on a ventile scale potentially occludes the reality that the estimated probabilities in the data used to develop the model are not regularly distributed. In other words, the one-to-twenty scale might obscure the fact that “risk,” by the AFST’s own definition, is concentrated among the highest-value numeric scores. There appears to be a steep drop-off in the estimated probabilities that the highest-tier range of AFST scores represent. As figure 2 demonstrates, there is, in fact, a greater gulf between the estimated probabilities that underlie AFST scores of twenty and nineteen, respectively, than exists between AFST scores of fifteen and one. This might differ starkly from the intuitive interpretation of a one- versus a fifteen-point difference in estimated “risk.” Further exaggerating the degree of risk is the AFST deployment policy of showing only the highest risk score (or a label based partly on that score) where more than one child lives in the household.85

These defining features of the AFST risk score are further confused by the way AFST scores are shown to call screeners. As various accounts have described, the AFST score is relayed using a color gradient “from green down at the bottom … through yellow shades to a vibrant red at the top.”86 This traffic signal color-coding and the evenly spaced color gradient is misleading. These design features suggest that the AFST score conveys the absolute risk that a referral will end in removal and that the difference in the estimated risk of removal from one number to the next is the same, as reflected in the “intuitive risk” gradient in figure 2 below. However, the actual risk of removal and degree of increase in risk from one ventile to the next is radically different—and lesser—as depicted in figure 2’s “actual risk” gradient.

Figure 2. AFST “risk” categories vs. percentage of screened-in referrals from 2010–2014 where a removal occurred within two years. Note that the AFST was not in use during the time period from which this data is drawn. The “risk” categories depict the AFST scores such referrals would have received if the tool had been in use during that time.

As figure 2 demonstrates, there is, in fact, a greater gulf between the actual removal rates that underlie AFST scores of twenty and nineteen, respectively, than exists between AFST scores of fifteen and one. This might differ starkly from the intuitive interpretation of a one- versus a fifteen-point difference in estimated "risk." Further exaggerating the degree of risk is the AFST deployment policy of showing only the highest risk score (or a label based partly on that score) where more than one child lives in the household. The decision, then, to use likelihood of removal by Allegheny County within two years as the proxy for child harm seems to reinforce existing County removal practices rather than to prevent child harm. And as future AFST scores will likely be based on County actions taken in response to past AFST scores (assuming the model is retrained on data generated after the AFST’s deployment), the use of the AFST threatens to create a feedback loop that might exacerbate past disparities in the family regulation system. These design features suggest that the AFST score conveys the absolute risk that a referral will end in removal and that the difference in the estimated risk of removal from one number to the next is the same, as reflected in the “intuitive risk” gradient in figure 2 below. However, the actual removal rate and degree of increase in removals from one ventile to the next is radically different—and lesser—as depicted in figure 2’s “actual risk” gradient.

C. The nonscience behind risk thresholds

The dividing lines, or thresholds, between low, medium, and high “risk” categories are not identified by scientific or statistical method.87 Rather, the scores that bound each risk tier are selected by the tool developer and/or agency personnel. The methodology reports describing the design of the various versions of the AFST do not clearly identify why particular scores—10 or 12, depending on the version of the AFST—were selected as the lowest consistent with designation of a referral as “low-risk.” Nor do the developers describe why a score of 18 was selected to trigger the “high-risk” designation. The County does compare how the AFST risk tiers and distribution of risk scores would compare to examples of rule-based thresholds, but it does not explain how the cutoffs for the AFST tiers were devised.

In contrast, when Oregon developed a predictive tool drawing on the AFST model, they were transparent about how they set the thresholds between the four risk tiers that they created. However, they, too, neglected to explain why this method was selected. In the Oregon model, the developers decided to make each successive risk tier reflect double the risk. (As explained earlier, despite using quintiles, the risk scores do not actually reflect a steady 5 percent increase in risk between one ordinal number and the next.) The Oregon developers also decided to include only 8 percent of children in the highest tier, and these parameters dictated where the cutoffs fell between their four tiers. Why these decisions were made is unknown, but ultimately it was a matter of governance and policy, not one of statistical outcomes or likelihood of risk. With the AFST, we know that they chose for their top category to represent 15 percent of children and, because of their aggregation methodology, 25 percent of cases; but, as with Oregon, the reason those percentages were selected is not clearly stated.

Through conversations with the County and documents reviewed by the ACLU and HRDAG, we learned that Allegheny County has made at least four major changes to the thresholds between risk tiers when creating Version 2 of the tool, which launched in December 2018.

First, in January 2019, Allegheny County made changes that were expected to double the prevalence of “high-risk protocol” labels from about 11.5 percent of referrals to about 22 percent.88 Based on the April 2019 methodology report describing Version 2 of the AFST, it seems the prevalence of referrals that trigger the “high-risk” protocol was slightly higher at 24 percent.89

Second, in October 2019, Allegheny County expanded the low-risk protocol definition. Whereas a referral previously triggered the “low-risk” protocol if the maximum score fell between one and ten and all children on the referral were twelve years old or older, the County in October 2019 lowered the age cutoff to seven years old and increased the score ceiling to a maximum of twelve. This change significantly increased the prevalence of the low-risk protocol by “siphon[ing] off some referrals that would have been Low-Range or Medium-Range previously,” “from around 4% of GPS referrals to over 20% (as was projected).”90

Third, around the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, the screen-in rate went through a noticeable dip. The dip was most pronounced for the high-risk protocol tier, starting around 66 percent in November 2019 and reaching its lowest point of 45 percent in March 2020 before rebounding to screen-in rates exceeding 90 percent. In discussions with Allegheny County about this trend, we learned that the County had been monitoring this fall and was “not comfortable” with the “slippage in concurrence with the tool.” While there was no written policy change, the County made its preferences clear to frontline staff through discussions, a method that appears to have worked. Referrals did not begin to dip until February 2020, a trend which lasted through July 2020.91 According to an internal memo on the impact of COVID-19, the demographics of families being referred did not change (though we note that the memo does not indicate whether other formally documented or orally conveyed changes were made to screening protocols that contributed to this result).92 This meant that they were required to make a report if they had “reasonable cause” to suspect child abuse, and some worried that the closure of schools meant that public eyes on children would lead to increased child injuries at home. However, this does not appear to have been the case, with the state Bureau of Child and Family Services explaining the increase in reports alleging abuse in 2021–2022 as “anticipated” because the agency had “been observing these increases following the significant decrease in the total suspected reports attributed to the COVID-19 pandemic.” Notably, the “totals still remain[ed] lower than in the year prior to the pandemic” and percentage of substantiated reports of child maltreatment moved from 14.3 percent in 2021 to 12.8 percent in 2022.93

Figure 3. Screen-in rates by GPS AFST Category, over time.

The County’s internal materials note that the next model reevaluation might “explore adjusting the tool’s structure or the definitions of any of the protocols to try to: (1) emphasize or deemphasize any ‘types’ of referrals, (2) account for child ages differently, [or] (3) attempt to influence racial disparities.”94 These policy changes may have had a significant impact on screening rates in Allegheny County, but none of them involved the input of impacted community members or were even publicly explained. Allegheny County may be one of the most transparent jurisdictions when it comes to sharing information about its predictive analytics tool, but even it falls short of full, meaningful transparency.

D.The political construction of administrative data

This approach ignores the policy-driven limits of government agencies’ administrative data. Much has been researched and written about how the use of criminal legal records that reflect racially discriminatory policing practices to build risk assessment algorithms can embed underlying systemic or structural biases in the predictive tool.95 In the context of the AFST, we have previously written about how the tool’s inclusion of juvenile probation system involvement and eligibility for certain public benefits as risk factors can raise the risk scores of households that include someone who is Black or has a history of seeking publicly funded behavioral healthcare services.96

In addition to importing the data that result from discriminatory policies and practices, using administrative data to build predictive risk assessment tools either ignores how government databases fail to reflect entire populations—for example, those who only access privately funded behavioral health services—or assumes that those excluded from the databases are unlikely to pose the risk being predicted. With the AFST, recall that the most common reasons for removal in Pennsylvania in 2020–2021 were (1) caregiver substance abuse, (2) neglect, (3) caretaker’s inability to cope, (4) inadequate housing, and (5) child’s behavioral problems. Individuals and families who can afford or otherwise have access to private health insurance, private substance abuse treatment programs, private behavioral or mental healthcare, and housing can address virtually every one of these adversities without information about them being recorded in government databases. Thus, the universe of risk factors that exists for these families will never be reflected in the administrative data used to build the AFST and other such tools.97

The limited worldview reflected in the administrative records used to build predictive models comes not just from the fact that they pertain to a subset of the population, but also from the limited set of data points contained within those records. In a family regulation system where laws, policies, and practices are built around a paradigm of parental fault, child welfare records reflect myriad data points about the parent but not other factors that contribute to, or perhaps even directly cause, the alleged child maltreatment. For instance, some scholars have noted that even though states receiving federal Title IV-E funding must make reasonable efforts to preserve and reunify families, the federal government’s collection of “circumstances of removal data fail to capture any information concerning the agency’s efforts to prevent removal, despite the fact that such efforts are clearly observable.”98 Similarly, though state and local child welfare agencies could track whether the services and programs that families are required to use and complete (and which particular providers) are associated with successful family reunification/preservation and which ones correlate with removals, this is not typically done. Such tracking could provide a deeper understanding of what features of the family regulation system are doing more harm (i.e., correlating with removal and not reunification) than good and could help identify interventions that are not addressing family needs. As one Allegheny County caseworker commented, “Risk of removal in two years is inherently going to be increased by our [CYF] involvement, because we’re the only ones that can remove the children.” Yet the administrative records used to build the AFST lack data points from which tool developers could identify types or aspects of CYF involvement that are more closely correlated with removal in two years.

E. The case for measuring impact over “accuracy”

Assessment of the AFST’s performance in terms of “accuracy” is misleading partly because this suggests the tool has the ability to foresee maltreatment across the entire population of the County when, as the foregoing discussion demonstrates, such a prediction task is not impossible. First, the AFST was designed to predict relative risk of removal, a proxy that even some of those using the tool believe to be a poor approximation of actual child maltreatment. Second, it was built with information about only a subset of the population—not because that subset was identified as a representative cross section of the County, but simply by administrative fiat. This group by definition includes the people about whom government agencies possess the most information, because those people use or are eligible for public benefits and social or health services, or because they are disproportionately targeted for surveillance and investigation. Yet the methodology reports and impact assessments for the AFST do not sufficiently address how the limits of administrative data might skew the quality of its predictions.

Instead, the 2019 County-commissioned impact evaluation examined data from the AFST deployed from 2016–2018 (Version 1) to see how use of the tool impacted “accuracy, workload, disparity and consistency outcomes for children involved in GPS referrals.”99 To assess accuracy of screened-in reports, evaluators determined the percentage that resulted in agency involvement past the initial investigation stage or a re-referral to the agency within two months of the first report.100 For screened-out referrals, the evaluators looked at the percentage that had no re-referral calls within two months.101 However, CYF caseworkers, agency leadership, and tool designers have separately stated that referral is a weak indicator of maltreatment. As an empirical matter, the County declines to investigate roughly 50 percent of all referrals simply because they do not meet threshold criteria for investigation. But perhaps most revealing is that Version 1 of the AFST (2016–2018) generated two risk scores, one based on the likelihood of child removal within two years and the other on the likelihood of a re-referral to protective services, but the County and tool developers dropped the re-referral risk proxy from subsequent versions. Why? Among other things, re-referral “was not as strongly linked to the primary outcome of concern, serious abuse and neglect.”102

If the measure of re-referral is ultimately unhelpful, an alternate measure of the AFST’s utility, particularly given the risk of harm from contact with the family regulation system, is the tool’s impact on screen-in rates: the percentage of screened-in referrals that, upon investigation, were accepted for service, connected to another open case, or connected to a closed case that was then reopened.103

Even if we set aside the fundamental flaw of calculating accuracy by looking at re-referral rates, the AFST’s impact, as assessed in the County-commissioned 2019 evaluation, amounted to only “moderate improvements in accuracy of screen-ins with small decreases in the accuracy in screen-outs, a halt in the downward trend in pre-implementation screen-ins for investigation, no large or consistent differences across race/ethnic or age-specific subgroups in these outcomes, and no large or substantial differences in consistency across call screeners.”104 Additionally, the “moderate improvements” in screen-in accuracy “attenuated somewhat over time.”105 In other words, on balance, the AFST had mixed results, with one exception: it clearly stopped the decrease in screen-in rates that had been occurring until the AFST was implemented. Interestingly, emerging studies of the impact of criminal legal risk assessment tools used by judges to help decide whether to release an accused individual pretrial, and tools used to inform sentencing decisions, indicate that the tools may have effects (including asymmetric effects) on judicial decision-making and individual outcomes in the short term, but that such impacts may attenuate over time.106

Given the impossibility of determining whether the AFST generated accurate risk scores or resulted in accurate screening decisions by call screeners, the tool designers came up with an imperfect model for doing so. But the inability to evaluate the tool’s accuracy in terms of real-world impact, does not mean we should ignore the fact that this alternate calculation is, at best, of questionable reliability and, at worst, irrelevant. The decision to assess the AFST’s utility using a misleading and speculative metric (accuracy) is particularly confusing when its impact can be measured in real-world, quantifiable ways—namely, impact on screen-in rates and racial disparities in screen-in rates.

III. Measurable Impacts of the AFST on Families

Because measures of the AFST’s “accuracy” obscure what the tool actually predicts or how the risk factors it weighs are skewed to the disadvantage of families and parents, we assess its utility in terms of the actual, tangible impact on families that it scored, specifically screen-in rates and racial disparities, using an equity framework.

A. Screen-in rates in Allegheny County did not decrease with the AFST

Based on the data reviewed by the ACLU and HRDAG, screen-in rates in Allegheny County do not appear to have dropped after introduction of the AFST in 2016. The screen-in rate is defined as the number of referrals that are screened in for investigation in a given period divided by the total number of General Protective Service referrals the County received during that time. (Call screeners have discretion to screen in or screen out GPS referrals, which are reports claiming neglect, but state law requires them to screen in CPS referrals, which are ones that involve allegations of abuse.) As the screening stage is the step in the investigative process the AFST most directly influences, the screen-in rate is also something the County can influence through the tool’s scoring methodology and accompanying policies.

In response to Associated Press reporting about the AFST’s impact, the County stated that its overall screen-in rate of approximately 50 percent, which includes both CPS and GPS referrals, is “in-line with similar statistics among other counties or states.”107 This comparison is of limited value since it does not address the possibility that all comparable jurisdictions could be screening in more referrals than needed. While the County says that they are unaware of any empirical evidence that these screen-in rates are too high, we do know that not all families screened in by the County move on to the next stage of having a case formally opened by the child welfare agency (otherwise known as being “accepted for services”). That is, upon closer investigation—which can entail interviewing the child or children implicated in the report, parents, neighbors, relatives, or teachers, among others—County workers have concluded that no maltreatment has occurred and the family is not in need of any services. Since the AFST sits at the front door of the protective service system, it could be used as a tool for reducing the number of families who are screened in in the first instance, to shield families from unwarranted state scrutiny through an investigation.

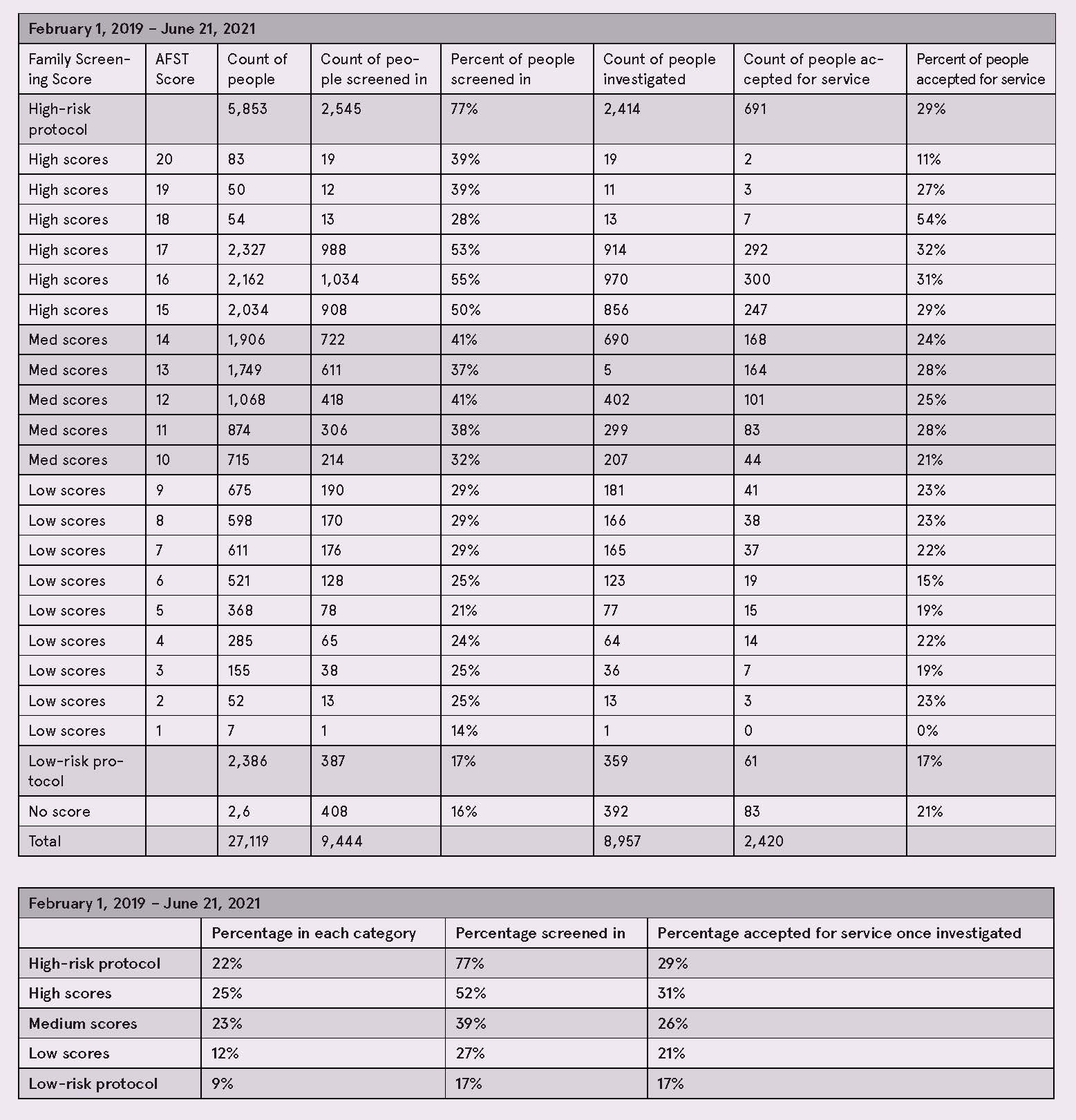

In addition, for the period from February 2019 through June 2021, almost half of all referrals were either within the “high-risk” protocol (22 percent of all referrals) or the high-score tier of fifteen to twenty (25 percent). By contrast, only 21 percent of referrals were within either the low-score tier of one to nine (12 percent) or the “low-risk” protocol (9 percent). Across all tiers, the vast majority of referrals did not lead to those families being “accepted for services,”108 an outcome that means the investigation resulted in an opened child welfare case and was accompanied by increased monitoring of the family by a caseworker.109 This relatively low case opening rate suggests that many more families are being investigated than “necessary,” even by Allegheny County’s own terms.

B. Racial disparities in screen-in rates did not decrease with the AFST

Racial disparities and disproportionality at the screening phase of Allegheny County’s child welfare system have the potential to reverberate through subsequent decision points and outcomes. Given the AFST’s role in screening decisions, it has the potential to reduce these differentials at the front end of the system even if the tool was not adopted to decrease disparities. Based on our analysis, racial disparities in screen-in rates have not decreased since launch of the AFST in 2016, notwithstanding the County’s claims to the contrary.110

Racial disproportionality occurs when the proportion of one racial group in the child welfare population (e.g., children or families at the screen-in stage, accepted for services, placed in foster care, etc.) is either proportionately larger (overrepresented) or smaller (underrepresented) than that racial group’s percentage of the general population. Racial disparities exist where the ratio of one racial or ethnic group at a particular event is not the same as the ratio of another racial or ethnic group who experienced the same event.

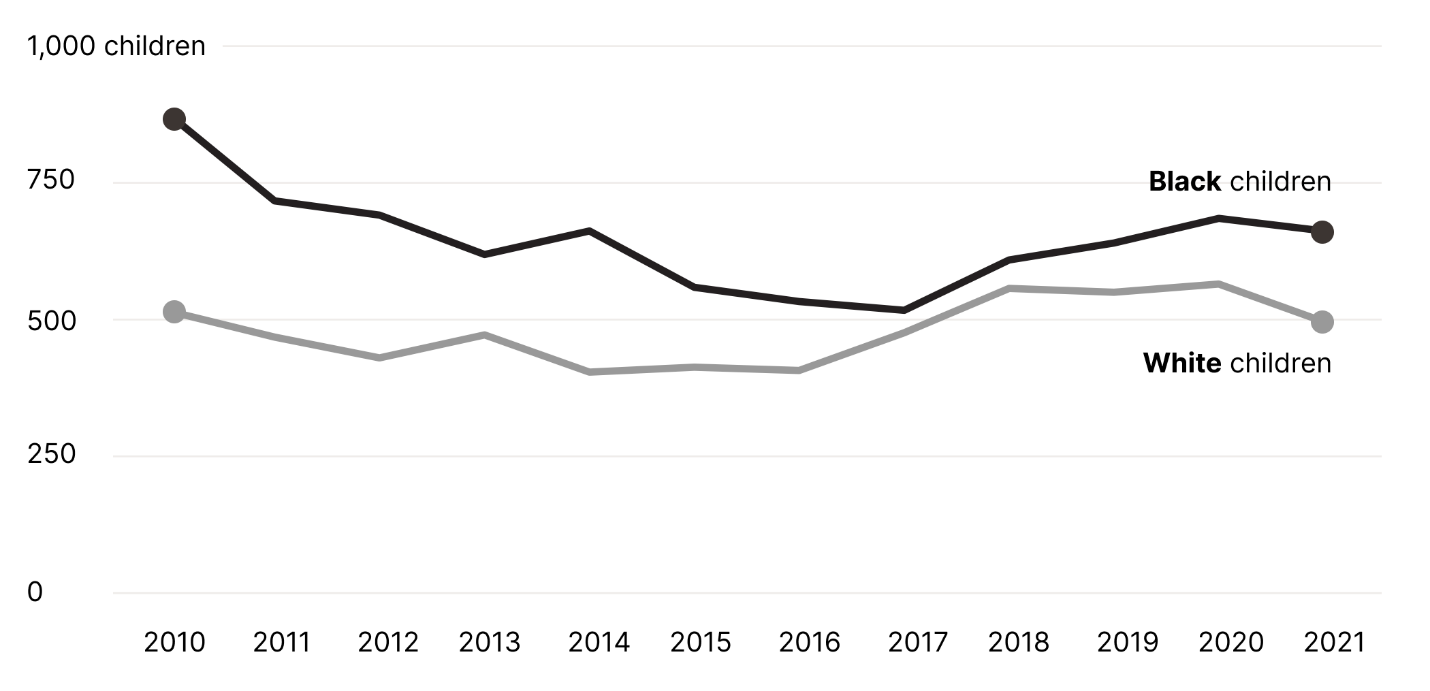

As figure 4 illustrates, for at least the past decade, Black children have consistently outnumbered white children in out-of-home placements in Allegheny County and are disproportionately overrepresented. For example, of the 1,463 children in an out-of-home placement on January 1, 2021, 45.2 percent were Black and only 33.9 percent were white. In contrast, in 2020, Black children made up only 17.8 percent of Allegheny County’s population of individuals under the age of nineteen, while white children comprised almost 67.5 percent.111

Figure 4. A comparison of the number of Black and white children separated from their families as of January 1 of each year.112

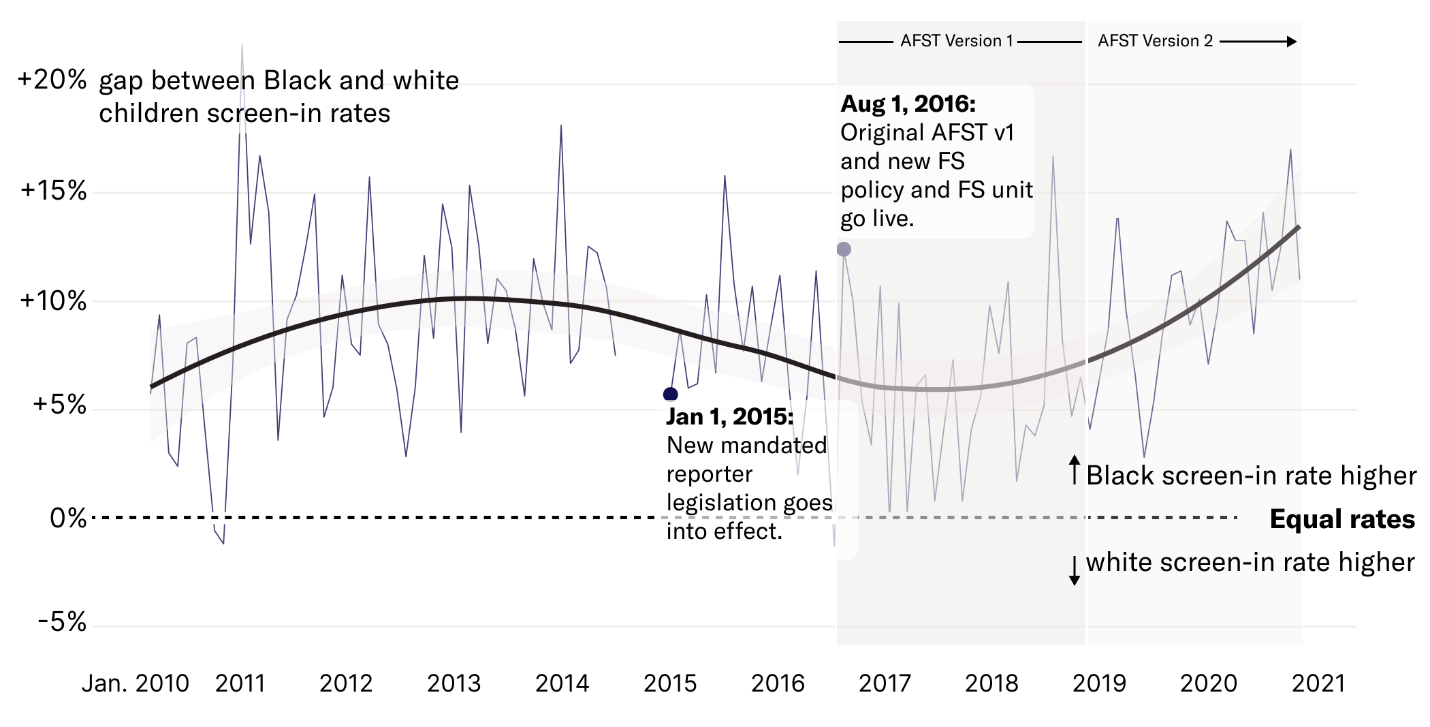

Until at least 2022, every two weeks the County held quality-assurance reviews, during which personnel examined racial disparities in screen-in rates. In its 2020–2021 reviews, the County notes the continued disparities in several of its quality-assurance reports. For example, a report from October 2020 noted that “it does appear the gap between black and white screening rates has been expanding gradually since perhaps early 2019,”113 while a report from June 2021 noted that “there continues to be a fairly stable level of disparity in screening rates between families of black children and families of white children, without controlling for AFST score.”114

Yet in 2022, the County stated that “implementation of the AFST, coupled with associated policies, has reduced racial disparities in screening decisions as well as case openings and removals to foster care.”115 A paper coauthored by the AFST’s creators about the disparities clarifies that the introduction of the AFST did not significantly affect disparities in screen-in decisions except among referrals within the highest-risk tier of scores.116 For the 2015–2020 referrals, the disparity in average screen-in rates between Black and white families with risk scores of nineteen or twenty was smaller in the roughly four years after the AFST was implemented as compared to the eighteen months before the AFST was implemented. This reduced disparity stems from a dramatically increased screen-in rate for both Black and white families. In the eighteen months before the AFST was implemented, white families with a risk score of nineteen or twenty were screened in, on average, 40 to 50 percent of the time, while Black families with the same scores were screened in 50 to 60 percent of the time. In the four years after the AFST's implementation, Black and white families with scores of nineteen or twenty were screened in at similar rates on average, between 60 and 70 percent of the time.117 Thus, the reduction in the racial disparity in this score range was not because the AFST was scoring proportionally fewer Black families as high-risk and therefore fewer were mandatorily screened in. Rather, the change in disparity was driven by the mandatory screen-in policy’s impact on bringing more white families in for investigation. This detail is significant because the racial-disparity critique is not simply about numbers but about what happens when a family is screened in: Black families are being subjected to disruptive and harmful investigations at greater rates than white families. Pulling in more black and white families and then shrinking the differential does nothing to address the harm that is at the heart of the disparity critique.

External research on the AFST and related tools further undercuts the County’s racial-equality narrative about the tool. Researchers from Carnegie Mellon University and other institutions found that if call screeners had followed the AFST’s recommendations for each report between August 2016 and May 2018, the screen-in disparity rate between Black and white children would have been 20 percent.118 However, in actuality, this disparity rate was 9 percent because screening workers did not defer to the AFST’s outputs.119 These findings suggest that human input—the same input the AFST creators discounted as far less reliable “intuitions and anecdotal evidence” in their proposal to build the tool120—has been critical to counteracting the tool’s racially disparate outputs. Rittenhouse et al. do not engage with this finding at all, instead offering the AFST as a case study in how “predictive risk models can serve to reduce disparities.”121

The Rittenhouse team also does not address the dramatic increase in average screen-in rates (in some cases upward of 20 percent) for both Black and white families that accompanied the decreased racial disparity in the highest score tier.122 This omission suggests an incomplete understanding of the concerns driving the racial inequity critique. The harm is not simply the numerical imbalance, (i.e., that Black and white families are screened-in in unequal ratios) but also the harm of being unnecessarily investigated, subjected to invasive state scrutiny, and having a record about them created in the County’s child welfare database, even if the allegations are deemed unfounded. Increasing the sheer number of Black (and white) families investigated by the state does not eliminate the injustice; it just opens more families to unwarranted dignitary and psychological harms and potential infringement of individual rights.

Figure 5. The racial gap in screen-in rates in Allegheny County from 2010 to 2020.123124125

While the AFST’s creators have touted the tool as a model for reducing disparities and focusing investigative efforts, this study hints at the possibility that, as a matter of the tool’s design, it may do the reverse.

1. J. Khadijah Abdurahman, Birthing Predictions of Premature Death, Logic 17 (August 2022), https://logicmag.io/home/birthing-predictions-of-premature-death/.

2. US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Administration for Children and Families, Child Maltreatment 2021, 19 ex.3–A (2022), https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/cb/cm2021.pdf.

3. Josh Gupta-Kagan, “Confronting Indeterminacy and Bias in Child Protection Law,” Stanford Law and Policy Review 33 (2022): 217, 233–38.

4. Family Involvement in the Child Welfare System, Hearing Before the NY State Assembly Standing Committee on Children and Families, 2021 Leg., October 21, 2021 Sess. (N.Y. 2021) (statement of New York Civil Liberties Union), https://www.nyclu.org/sites/default/files/field_documents/211021-testimony-familyregulation_0.pdf. (“[T]hose investigated by [the child welfare system] experience it as a stressor that puts their families under a microscope and threatens them with separation.”); id. (statement of Desseray Wright, JMac for Families, at 1:17:26), https://nystateassembly.granicus.com/MediaPlayer.php?view_id=8&clip_id=6408. (“[M]ost parents who have dealt with [protective services] have the same reaction. It is a traumatic situation… when [protective services] comes into your home, it doesn’t feel like they are there to help you.”); ACLU and Human Rights Watch, “If I Wasn’t Poor, I Wouldn’t Be Unfit”: The Family Separation Crisis in the U.S. Child Welfare System (November 2022).

5. Josh Gupta-Kagan, “Toward a Public Health Legal Structure for Child Welfare,” Nebraska Law Review 92 (2014): 897, 903; Cynthia Godsoe, “Parsing Parenthood,” Lewis and Clark Law Review 17, no. 113 (2013).

6. ACLU and Human Rights Watch, “If I Wasn’t Poor” (quoting NYU law professor Chris Gottlieb).

7. Anna Arons, “The Empty Promise of the Fourth Amendment in the Family Regulation System,” Washington University Law Review 100 (2023): 1057; Gupta-Kagan, “Child Welfare.”

8. See, for instance, Hyunil Kim et al., “Lifetime Prevalence of Investigating Child Maltreatment among US Children,” American Journal of Public Health 107, no. 274 (2017): 278.

9. Kim et al., “Lifetime Prevalence”; see also Frank Edwards et al., “Contact with Child Protective Services Is Pervasive but Unequally Distributed by Race and Ethnicity in Large U.S. Counties,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 118, no. 30: “In most counties [studied], having had a CPS investigation was a modal outcome for Black children.”

10. Alan J. Detlaff and Reiko Boyd, “Racial Disproportionality and Disparities in the Child Welfare System: Why Do They Exist, and What Can Be Done to Address Them?,” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Sciences 692 (2020): 253, 254n1; Geen et al., “Welfare Reform’s Effect on Child Welfare Caseloads,” The Urban Institute, 11. See also Annie E. Casey Foundation, “Children in Foster Care by Race and Hispanic Origin in United States,” Kids Count Data Center (https://datacenter.aecf.org), estimating that, in 2020, of all children in foster care, 22 percent were Hispanic or Latino, 23 percent were non-Hispanic Black, and 2 percent were non-Hispanic American Indian. Compare Annie E. Casey Foundation, “Child Population by Race & Ethnicity in United States,” Kids Count Data Center, estimating that, of the total US population age under eighteen, 26 percent was Hispanic or Latino, 14 percent was non-Hispanic Black, and 1 percent was non-Hispanic American Indian.

11. See Skiler Leonard, Allison A. Stiles, and Omar G. Gudiño, “School Engagement of Youth Investigated by Child Welfare Services: Associations with Academic Achievement & Mental Health,” School Mental Health 8, no. 3 (2016): 386; Christina Dimakosa et al., “Aspirations Are Not Enough: Barriers to Educational Attainment for Youth Involved with Child Welfare,” European Educational Researcher 5 (2022): 105 (showing similar outcomes in a longitudinal study of Canadian youth).

12. See, for instance, Phyllis Gyamfi et al., “The Relationship between Child Welfare Involvement and Mental Health Outcomes of Young Children and their Caregivers Receiving Services in System of Care Communities,” Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders 20 (2010): 211; Barbara J. Burns et al., “Mental Health Need and Access to Mental Health Services by Youths Involved with Child Welfare: A National Survey,” Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 43 (2004): 960.

13. Sydney Goetz, “From Removal to Incarceration: How the Modern Child Welfare System and Its Unintended Consequences Catalyzed the Foster Care-to-Prison Pipeline,” University of Maryland Law Journal of Race, Religion, Gender and Class 20 (2020): 289, 294–95; Melissa Jonson-Reid and Richard P. Barth, “From Placement to Prison: The Path to Adolescent Incarceration from Child Welfare Supervised Foster or Group Care,” Children and Youth Services Review 22 (2000): 493; Ashly Marie Yamat, “The Foster Care-to-Prison Pipeline,” Justice Policy Journal 17 (2020): 1. But, see E. Jason Baron and Max Gross, “Is There a Foster Care-to-Prison Pipeline? Evidence from Quasi-Randomly Assigned Investigators,” National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper No. 29922 (April 2022), available at https://www.nber.org/papers/w29922.

14. “DHS Offices,” Allegheny County Department of Human Services, https://www.alleghenycounty.us/Human-Services/About/Offices.aspx.

15. 55 Pa. Admin. Code § 3490.223 (West 2022).

16. Jeremy D. Goldhaber-Fiebert and Lea Prince, Impact Evaluation of a Predictive Risk Modeling Tool for Allegheny County’s Child Welfare Office (2019), https://www.alleghenycountyanalytics.us/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Impact-Evaluation-from-16-ACDHS-26_PredictiveRisk_Package_050119_FINAL-6.pdf. “Child protective services” (CPS) in other contexts often refers to a jurisdiction’s child welfare agency. In this paper, from this point forward, we use “CPS” specifically to refer to the category of referrals required to be investigated.

17. Goldhaber-Fiebert and Prince, Impact Evaluation.

18. Pennsylvania Department of Human Services, Child Protective Services 2020 Annual Report (2021), 37–38, available at https://www.dhs.pa.gov/docs/Publications/Documents/Child%20Abuse%20Reports/2020%20Child%20Protective%20Services%20Report_FINAL.pdf

19. Pennsylvania Department of Human Services, Child Protective Services 2021 Annual Report (2022): 39–40, available at https://www.dhs.pa.gov/docs/OCYF/Documents/2021-CPS-REPORT_FINAL.pdf.

20. Pennsylvania Department of Human Services, Child Protective Services 2021 Annual Report (2022): 40–41, available at https://www.dhs.pa.gov/docs/OCYF/Documents/2021-CPS-REPORT_FINAL.pdf.

21. Pennsylvania Department of Human Services, Child Protective Services 2022 Annual Report (2023), available at https://www.dhs.pa.gov/docs/OCYF/Documents/2022-PA-CHILD-PROTECTIVE-SERVICES-REPORT_8-10-2023_FINAL.pdf.

22. The terminology and categories are taken from state reports. See Pennsylvania DHS, Child Protective Services 2022 Annual Report, 42. Although broad descriptors like “behavioral health … concerns” make it difficult to discern exactly what these categories represent, they offer a coarse vision of the kinds of circumstances that might lead to a determination of neglect. Struggles with substance use, difficulty accessing services like mental health or occupational therapy, the inability to access reliable childcare or adequate housing, and challenges resulting in consistent low attendance seem to be the types of concerns that most commonly result in an administrative determination of neglect.

23. Pennsylvania Department of Human Services, Racial Equity Report 2021, 2, 13, https://www.dhs.pa.gov/about/Documents/2021%20DHS%20Racial%20Equity%20Report%20final.pdf.

24. Pennsylvania DHS, Racial Equity Report 2021, 13.

25. See, generally, Vivek S. Sankaran, “Parens Patriae Run Amuck: The Child Welfare System’s Disregard for the Constitutional Rights of Nonoffending Parents,” Temple Law Review 82 (2009): 55 .

26. See, for instance, In the Interest of K.A.W. and K.A.W., 133 S.W.3d 1 (2004); Wisconsin v. Yoder, 406 U.S. 205 (1972); Pierce v. Soc’y of Sisters, 268 U.S. 510 (1925) (recognizing right to direct upbringing and education of children); Meyer v. Nebraska, 262 U.S. 390 (1923) (recognizing right “to establish a home and bring up children”).

27. Glucksberg, 521 U.S., 753–54.

28. Stanley v. Illinois, 405 U.S., 645, 651 (1972).

29. See, generally, Eli Hager, “In Child Welfare Cases, Most of Your Constitutional Rights Don’t Apply,” ProPublica, December 29, 2022, https://www.propublica.org/article/some-constitutional-rights-dont-apply-in-child-welfare.

30. Katz v. United States, 389 U.S. 347 (1967); Torres v. Madrid, 141 S. Ct. 989 (2021); Terry v. Ohio, 329 U.S. 1 (1968); Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U.S. 335 (1963).

31. Balt. Dep’t of Social Servs. v. Bouknight, 492 U.S. 549 (1990).

32. See Tarek Z. Ismail, “Family Policing and the Fourth Amendment,” California Law Review 111 (2022). See also Benjamin R. Picker and Jonathan C. Dunsmoor, “Social Services and Constitutional Rights, a Balancing Act,” American Bar Association (February 11, 2013), https://www.americanbar.org/groups/litigation/committees/childrens-rights/articles/2013/social-services-constitutional-rights-balancing-act/.

33. See Eli Hager, “Police Need Warrants to Search Homes. Child Welfare Agents Almost Never Get One,” ProPublica, October 13, 2022, https://www.propublica.org/article/child-welfare-search-seizure-without-warrants; Arons, “Empty Promise.”

34. J.B. ex rel,. Y.W.-B., 265 A.3d 602, 624, 625 (Pa. 2021).

35. Arons, “Empty Promise,” 1057, 1088nn171–72, 174–75.

36. See Anna Belle Newport, “Civil Miranda Warnings: The Fight for Parents to Know Their Rights during a Child Protective Services Investigation,” Columbia Human Rights Law Review 54 (2023): 1; Arons, “Empty Promise, 36–37.

37. See ACLU and Human Rights Watch, “If I Wasn’t Poor, I Wouldn’t Be Unfit,” https://www.hrw.org/report/2022/11/17/if-i-wasnt-poor-i-wouldnt-be-unfit/family-separation-crisis-us-child-welfare: “Parents interviewed … lived in constant fear of caseworker retaliation. We heard several accounts of parents who believed they had been retaliated against when they tried to assert their rights, raise concerns, and advocate for themselves or their children. As a result, despite their anger and distress … parents said they were afraid of showing any reaction or emotion.” Abdurahman, Birthing Predictions, recounting that in a protective services investigation, “it never matters whether you are a good parent or a bad one—the family police will look for whether you roll down” and comply.

a. A federal survey of protective service agents’ decision-making found that “caregiver cooperation” was the modal factor agents cited as influencing their decision on how to dispose of an investigation, “rais[ing] the concern that clients who have a legitimate concern about the way their cases are being handled may be disadvantaged if they seem uncooperative.” US Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families “CPS Sample Component Wave 1 Data Analysis Report 4-15,” National Survey of Child and Adolescent Well-Being (April 2005), https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/opre/cps_report_ revised_090105.pdf.

38. Arons, “Empty Promise, ” 36–37.

39. J.B. ex rel. Y.W.-B., 2265 A.3d 602 (Pa. 2021).

40. See, for instance, Shalonda Curtis-Hackett, “Stop Weaponizing Protective Services,” New York Daily News, November 8, 2021, https://www.nydailynews.com/opinion/ny-oped-stop-weaponizing-child-protective-services-20211108-lkjhewmtlzb wljj2fmfneokswu-story.html: “The caseworker issued an ultimatum: I could comply with her investigation and ongoing surveillance or she would involve police or Family Court. I didn’t really know my rights and the last thing I needed was more threats to my children’s safety, so I complied.”

41. Virginia Eubanks, Automating Inequality (2018), quoted in Bridget Lavender, “Coercion, Criminalization, and Child ‘Protection’: Homeless Individuals’ Reproductive Lives,” University of Pennsylvania Law Review 169 (2021): 1607, 1666.

42. Josh Gupta-Kagan, “American’s Hidden Foster Care System,” Stanford Law Review 72 (2020), 841, 851–52 (describing how “safety plans” can effectuate changes in physical custody); Lizzie Presser, “How ‘Shadow’ Foster Care Is Tearing Families Apart,” New York Times, December 1, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/12/01/magazine/shadow-foster-care.html; Roxanna Asgarian, “Hidden Foster Care: All of the Responsibility, None of the Resources,” Appeal, December 21, 2020, https://theappeal.org/hidden-foster-care/. But, see Croft v. Westmoreland Cnty. Child. & Youth Servs., 103 F.3d 1123 (1997) (suggesting that safety plans based on the threat of child removal are inherently coercive and require some due process protections).

43. ACLU and Human Rights Watch, “If I Wasn’t Poor,” 55.

44. Kelley Fong, “Concealment and Constraint: Child Protective Services Fears and Poor Mothers’ Institutional Engagement,” Social Forces 97 (2018): 1785.

45. Brief of Amicus Curiae ACLU Supporting Plaintiffs-Appellees Subclass A & Supporting Affirmance, Nicholson v. Scoppetta, 116 Fed. App’x 313 (2d Cir. 2004) (arguing that the threat of investigation and removal by protective services can encourage domestic-violence survivors to seek “to avoid official notice,” “aggravate[ing] the loss of control” experienced by these communities and “deter[ring] them from breaking free from their abusers”).

46. Stephanie Clifford, “When the Misdiagnosis Is Child Abuse,” Marshall Project, August 20, 2020, https://www.themarshallproject.org/2020/08/20/two-families-two-fates-when-the-misdiagnosis-is-child-abuse; see also Pamela Davies, “The Impact of a Child Protection Investigation: A Personal Reflective Account,” Journal of Child and Family Social Work 16 (2011): 201, 202.

47. Judy Hughes, Shirley Chau, and Lisa Vokrri, “Mother’s Narratives of Their Involvement with Child Welfare Services,” Affilia: Journal of Women and Social Work 31 (2016): 1, 6 (documenting the experiences of thirty-two Canadian mothers with histories of system involvement).

48. Anna Brown et al., “Toward Algorithmic Accountability in Public Services,” CHI ’19: Proceedings of CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (2019): 7, https://dl.acm.org/doi/pdf/10.1145/3290605.3300271.

49. Joseph Goldstein et al., The Best Interests of the Child: The Least Detrimental Alternative (1996), 97 (quoted in Arons, “Empty Promise,” 1057, 1073.

50. Casey Family Programs, Issue Brief, How Does Investigation, Removal, and Placement Cause Trauma for Children? (updated May 2018), 2, https://caseyfamilypro.wpenginepowered.com/media/SC_Investigation-removal-placement-causes-trauma.pdf; Amanda Anger, “Unjust, Coercive Police Interviews Are Traumatizing Children of Color,” TruthOut, September 12, 2019, https://truthout.org/articles/unjust-coercive-police-interviews-are-traumatizing-children-of-color/ (describing interviews in Child Advocacy Centers, where “children sit isolated from their loved ones as police grill them for long periods of time. Interviews sometimes include a strip search.”); Hager, “Police Need Warrants” (quoting a children’s rights advcoate’s view that “for the child, [investigations are] about bodily integrity”; and quoting an affected parent’s difficulty “figur[ing] out how to talk to her sons about that time when strangers came in the middle of the night to take them away—all because she’d tried to guard them and their home. ‘This shouldn’t be in their memory, and it kills me that I can’t take it out,’ she said.”).

51. ACLU and Human Rights Watch, “If I Wasn’t Poor, I Wouldn’t Be Unfit.”

52. Colleen Kraft, American Academy of Pediatrics, “AAP Statement Opposing Separation of Children and Parents at the Border,” Press Release, May 8, 2018, https://www.aap.org/en/news-room/news-releases/aap/2018/aap-statement-opposing-separation-of-children-and-parents-at-the-border/; see William Wan, “What Separation from Parents Does to Children: ‘The Effect Is Catastrophic,’ ” Washington Post, June 18, 2018, https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/health-science/what-separation-from-parents-does-to-children-the-effect-is-catastrophic/2018/06/18/c00c30ec-732c-11e8-805c-4b67019fcfe4_story.html; William Wan, “The Trauma of Separation Lingers Long after Children Are Reunited with Parents,” Washington Post, June 20, 2018, https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/health-science/the-trauma-of-separation-lingers-long-after-children-are-reunited-with-parents/2018/06/20/cf693440-74c6-11e8-b4b7-308400242c2e_story.html. See also Vivek Sankaran, Christopher Church, and Monique Mitchell, “A Cure Worse Than the Disease? The Impact of Removal on Children and Their Families,” Marquette Law Review 102 (2019): 1161, 1166–69.

53. See Eli Hager, “The Hidden Trauma of ‘Short Stays’ in Foster Care,” Marshall Project, February 11, 2020, https://www.themarshallproject.org/2020/02/11/the-hidden-trauma-of-short-stays-in-foster-care; Vivek Sankaran and Christopher Church, “Easy Come, Easy Go: The Plight of Children Who Spend Less than Thirty Days in Foster Care,” University of Pennsylvania. Journal of Law and Social Change 19 (2016): 220 fig. 5.

54. Shanta Trivdei, “The Harm of Removal,” New York University Review of Law and Social Change 43 (2019): 523.

55. See, for instance, Roxanna Asgarian, “His Siblings Were Killed by Their Adoptive Mother. He Was Left in Foster Care to Suffer a More Common Fate,” Washington Post, December 11, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/his-siblings-were-killed-by-their-adoptive-mother-he-was-left-in-foster-care-to-suffer-a-more-common-fate/2019/12/11/f54f793a-d654-11e9-9610-fb56c5522e1c_story.html; Michael Levenson, “Scores of Massachusetts Children Mistreated in Foster Homes,” Boston Globe, September 1, 2015, https://www.bostonglobe.com/metro/2015/09/01/report/KmxuJqL5RAFy9bPZ39WVIN/story.html; see National Coalition for Child Protection Reform, Foster Care vs. Family Preservation: The Track Record on Safety and Well-Being, 1; Mary I. Benedict and Susan Zuravin, Factors Associated with Child Maltreatment by Family Foster Care Providers (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University School of Hygiene and Public Health, 1992), 28–30 (reporting that in Baltimore, the rate of substantiated sexual abuse in foster homes was four times that of the general population); J. William Spencer and Dean D. Knudsen, Out-of-Home Maltreatment: An Analysis of Risk in Various Settings for Children, Children and Youth Services Review 485 (1992): 14 (reporting that in Indiana, the rate of sexual abuse in foster homes was twice that in the general population, and the rate of physical abuse was triple that in the general population).

56. Elissa Glucksman Hyne et al., Unsafe and Uneducated: Indifference to Dangers in Pennsylvania’s Residential Child Welfare Facilities, Education Law Center and Children’s Rights (2018), 9 https://www.childrensrights.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/2018_Pennsylvania-Residential-Facilities_Childrens-Rights_Education-Law-Center.pdf.

57. Shanta Trivedi, “The Harm of Child Removal,” New York University Review of Law and Social Change 43 (2019): 549; Peter J. Pecora et al., Improving Family Foster Care: Findings from the Northwest Foster Care Alumni Study (2005), 30; Delilah Bruskas and Dale H. Tessin, “Adverse Childhood Experiences and Psychological Well-Being of Women Who Were in Foster Care as Children,” Permanente Journal 17, no. 3 (2013): 134.

58. Pecora et al., Improving Family Foster Care, 1.