I. “WE SEE YOU”

In my short film All Eyes on Us, Joe Biden says, “Your president sees you”—an affirmation, or a threat? Later I distort these words into “The anti-transgender … state … sees you.”

Transition is infinite motion. To transition is to sit in the inescapable space between violence and possibility. It is both to mourn death and to revere life—to feel the ache of a burning body and still insist on the exigency of something beyond. My last semester of college was marked by this peculiar kind of grief everywhere I turned. Simultaneously, as I began to rid myself of the ill-fitting garb I was taught to call “manhood,” I prepared to leave the embrace of a community that felt like a first sanctuary. I was contending with the looming demand to build a home anew, in an increasingly uninhabitable world rife with genocides that I found myself both complicit in and terrified by.

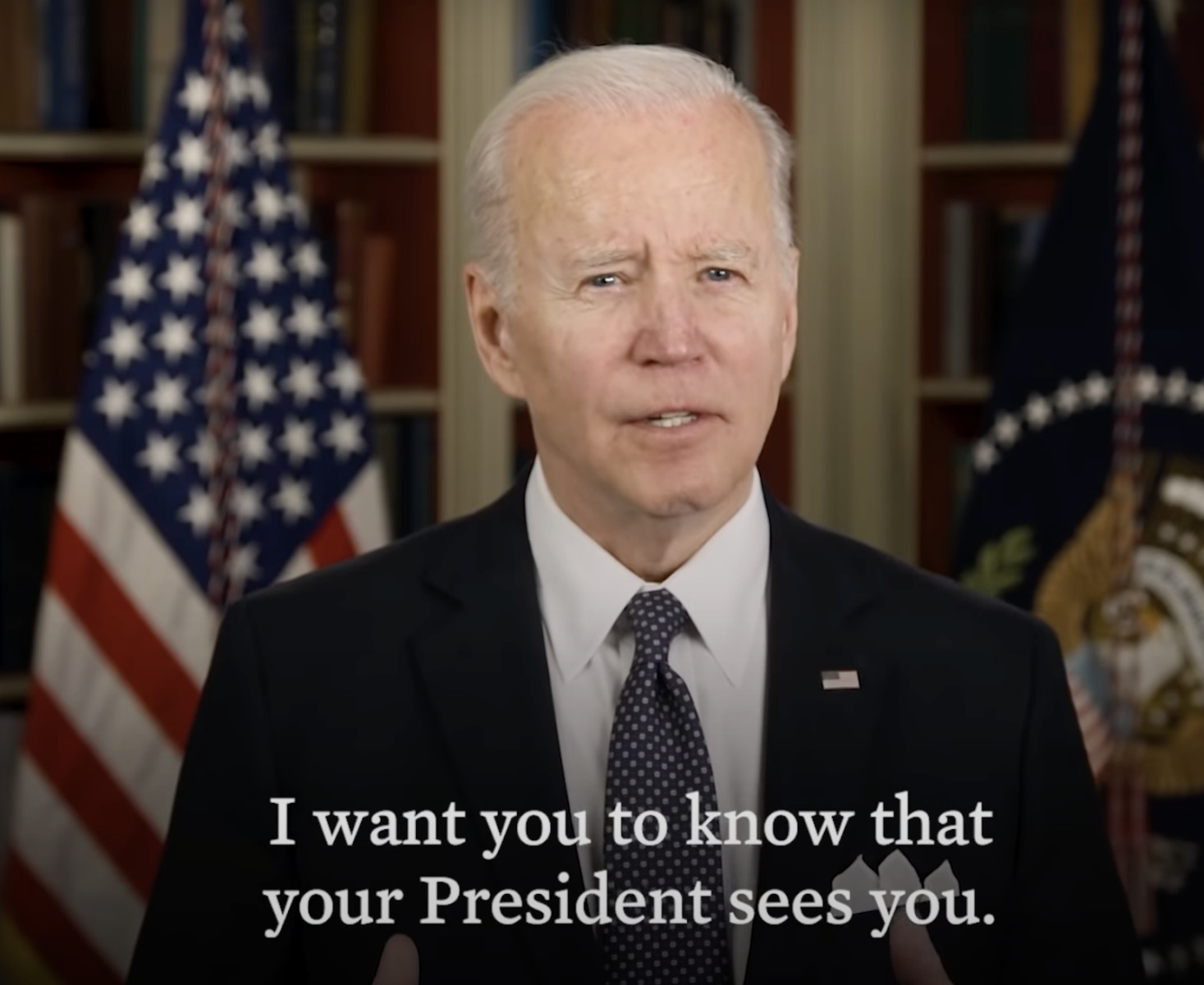

In my senior thesis, I attempted to study part of my own relationship to this violence, researching the brahminical, colonial, and Islamophobic project of state surveillance in India. Meanwhile, as a student in Julie Mallozzi and Pauline Shongov’s filmmaking seminar, I encountered the moving image as a novel medium to capture similar discomforts about transness and visibility at a time in my life deeply (dis)-colored by gender (among other forms of) trouble. In my final eight-minute documentary, I paired staged footage of myself and queer/trans friends’ eerie over-application of makeup with neoliberal platitudes celebrating International Transgender Day of Visibility (TDOV) and gendered facial-recognition algorithms from Visage SDK, an incredibly lucrative face-tracking software framework developed by Swedish computer vision company Visage Technologies AB. The film was guided by the questions: How does the representational goal of trans visibility reproduce the settler-colonial/brahminical/anti-Black cisheteropatriarchal gaze that has ravaged trans-of-color life and joy into a site of consumption and monitoring? How are the sacred practices of trans adornment (decorating, destroying, recreating ourselves in the mirror) made legible, extractible, and visible to the algorithm?

II. “WE RECOGNIZE YOU”

If liberal sensibilities are to be believed, American institutions of cultural life have, in the last decade, begun in earnest to make room for trans assertions—what Time magazine in 2014 declared a “transgender tipping point.”1 Yet, as filmmaker Tourmaline, gender and sexuality scholar Eric A. Stanley, and art historian Johanna Burton contend in their edited volume Trap Door, “[T]hese doors [into visibility] are almost always also ‘traps’—accommodating trans bodies, histories, and culture only insofar as they can be forced to hew to hegemonic modalities.”2 As a consequence of the representational impulses that have poisoned many of our most radical discourses, trans bodies—especially trans women’s bodies—have, in the name of “visibility,” been increasingly splayed out for consumption by a ravenous public and a targeting by a carceral state.

Such critique is indebted to Black trans studies: for, as theorist Che Gossett reminds us, part of the incommensurability of a trans-visibility politic with Blackness lies in its failure, in the first place, to account for the specificities of slavery and settler colonialism in exacting violent sex and gender binaries.3 Scholar-activist Jasbir Puar warns us about the lethal underbelly of increased queer and trans visibility within the American metropole: namely homonationalism, the framework by which we, as diasporic queer folks, are made into productive, mainstream, and law-abiding figures solely vis-à-vis the concurrent disembodiment of Orientalized, sexualized, and racialized terrorists. Theorists like micha cárdenas have noted that respectable claims to the visibility of (some) trans people are only possible by way of the managed disposability of others—diluting, co-opting, and essentializing a historically radical, ungovernable subject position for profit-making ends.4

As I studied these linkages more deeply, I grew curious for an artistic medium to animate these life-giving theories, articulated most saliently by Black, Dalit, Muslim, and Indigenous trans scholars. Particularly as a student of computer science and a software engineer, I have grown most concerned with recent innovations in facial recognition technology (FRT) innovation, which threaten to intensify the (hyper)visibility of racialized trans people living within the surveillance state. These technologies are broadly resonant with the biometric intrusions increasingly normalized as part of life for colonized trans communities living under right-wing settler projects, from the US to India to Israel. Particularly in this moment, as we witness with horror the technologically facilitated genocide in occupied Palestine and its violent homonationalist justifications, it is more important than ever that we commit ourselves to a free Palestine, from the river to the sea—not in spite, but because of an unwavering commitment to a truly trans politic.

III. “WE DOCUMENT YOU”

Effective filmmaking demands the impossible task of “making the familiar strange,” as my classmate Lorenzo once noted. As I embarked on my own documentary journey with burning questions about trans visual culture, I thus began with my chosen family—because who else?

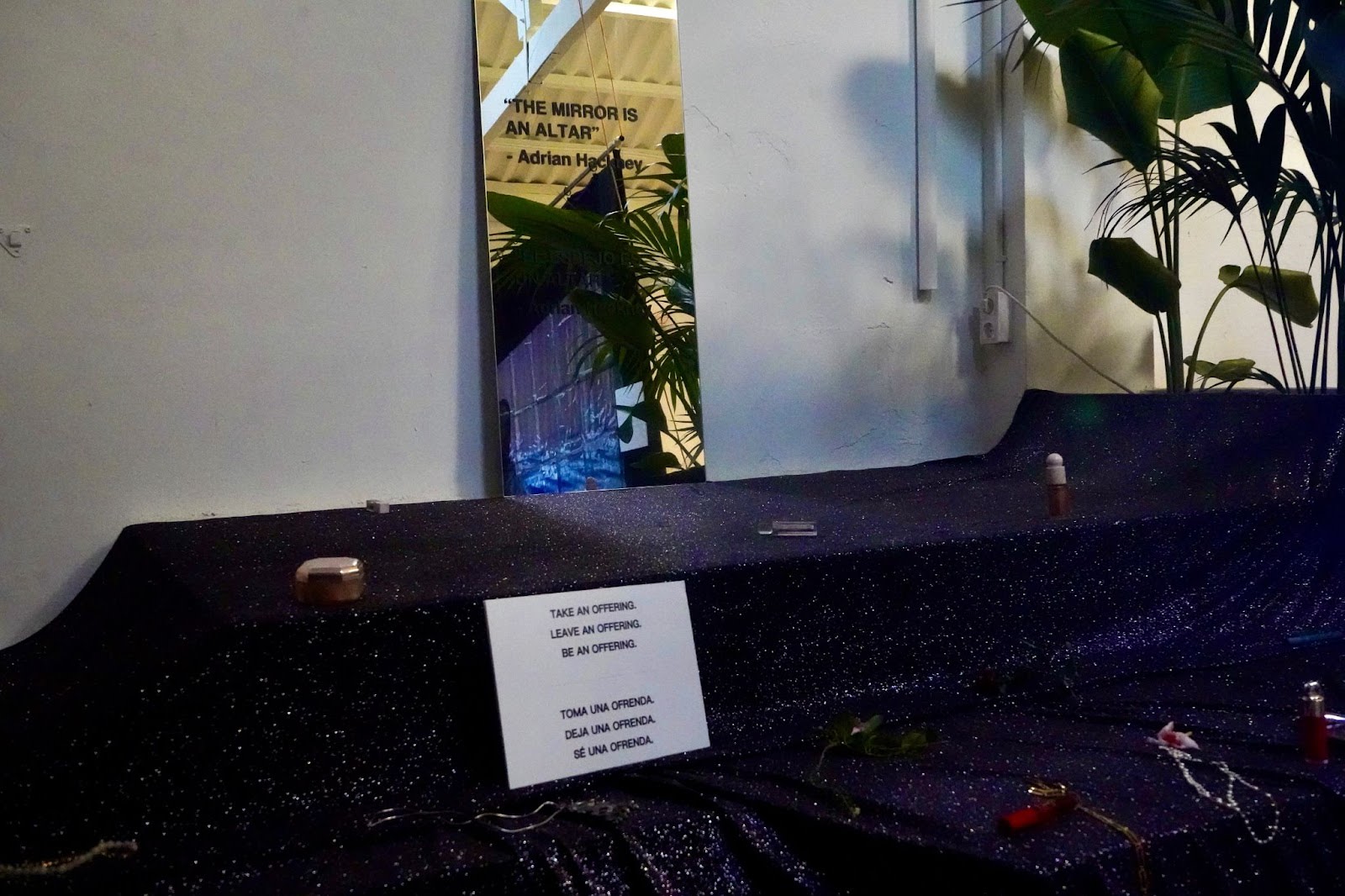

Two years ago, my best friend, Bhargavi, taught me how to wear makeup for the first time. Clumsy and uneven as my hand was back then, I immediately understood the banal gravity of it all. Beating my face quickly grew to be a most sincere daily ritual: each and every morning since, I have steadfastly committed to the unraveling and re-becoming of myself in my waking reflection. Sometimes, I reverently completed this self-offering with dangly earrings borrowed from my roommate Gabi’s wardrobe or nails shimmering in ungodly length. As my kin Adrian once told me in words I will never forget, the mirror is our altar, and to it, I made myself a faithful disciple.

Camera in hand, I thus turned first to these communal rites we cultivated together—a love letter to these sites of beauty and extraction. My first shots were rudimentary and aimless: in the darkness of my single dorm room, I asked Bhargavi to draw searing pink and blue eyeliner strokes across their eyelids, forehead, and other parts of their face. In grainy soft focus, we laughed at the dancing ink for hours. After incorporating feedback to sharpen and extend the concept, I more seriously crystallized my inclinations into staging three measured cosmetic acts, each sacrosanct in their own way—flicking mascara on an eyelash (done by Gabi), dabbing powder on a cheek (done by Adrian), painting tint on a lip (done by Bhargavi). Indebted to the rage, cadence, and unorthodox form of Marlon Riggs’s 1989 documentary Tongues Untied (which captures the intricacies of Black gay life),5 I fixed my lens into a closed-circuit TV (CCTV) camera of its own to intrude on these rituals with unrelenting duration, using parametrically staged shots to create discomfort in the viewer.6 Meanwhile, I learned from Sarah Hennies’s Contralto—an hour-long experimental performance piece comprised of strings, percussion, and video—that blending heterogeneously mundane and discordant sounds can open a conduit from which a plurivocal trans hymn can emerge.7 With a motley audio track of clicking mascara sticks, slithery gloss smacks, and pulsating powder thumps, I thus arrived at unnerving as a mode of critique.

March 31—the fifteenth TDOV—felt particularly hollow this year. In this moment of deadly transphobia, to exist in drag is chillingly unsafe, genderqueer children are institutionally denied lifesaving health care, and each new headline washes in with a new killing—all while millions of people and dollars funnel into the incredibly visible consumption of (especially Black) trans aesthetics and culture in pop-cultural world tours and television shows.8 Amid this incalculable loss and rage, the emptiness and eeriness of hearing war-criminal politicians professing to benevolently gaze upon us is what inspired my second filmic intervention. The first time I watched President Joe Biden’s 2022 TDOV speech, I couldn’t tell whether to shudder or laugh; the empty insistence that he is watching us, Vice President Kamala Harris is watching us, the entire administration is watching us, punctuated by the divine imagery that we are “made in the image of God,” made for a cocktail of almost comical violence.

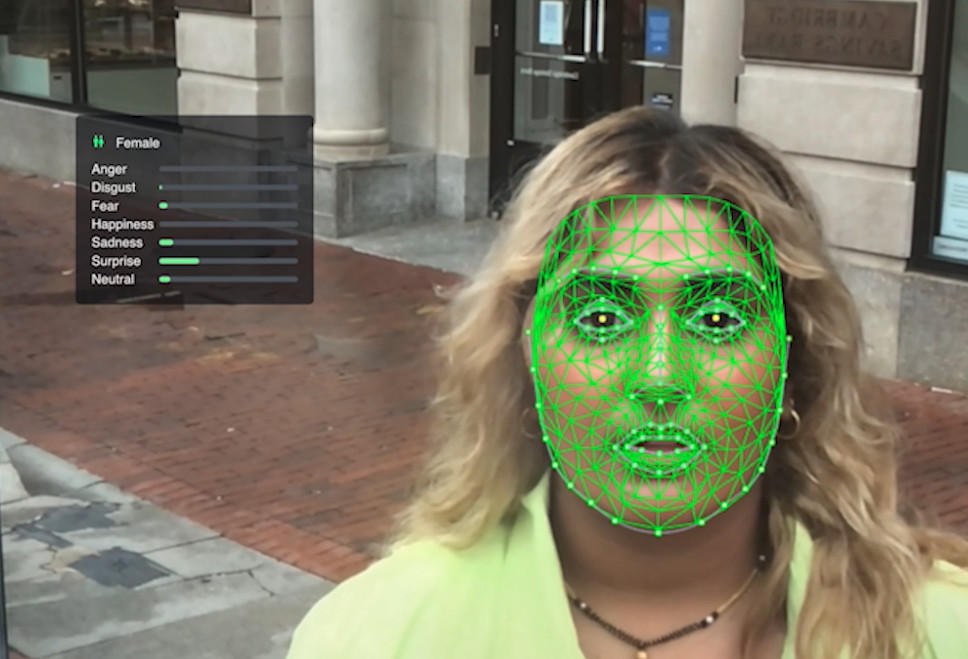

My academic research made clear to me the CCTV sensors dotting street signs from North East Delhi to Oakland are rapidly creating new rhythms of scrutiny and distorted paradigms of visibility. To be clear, the surveillance “cis-tem” (as recent scholarship has termed it) of sexual and gender minorities harkens back centuries, to various projects of domination across the world.9 However, automatic gender recognition (AGR) algorithms, along with recent data-driven trans registries in states like Florida and Missouri, now promise, in optimized time, to single out gender divergence and load us as ready targets for state-sponsored attack.10 Holding this violence in the quiet of the editing room, I decided to sheepishly pass euphoric footage of myself and my loved ones through Visage SDK’s facial-analysis and gender-recognition algorithm for the sake of critique.11 The quantified emotional ranges and assigned male/female binary identifiers were disquieting to begin with, and nauseating when paired with the list of hundreds of corporate and academic “satisfied clients.”12

My film ends with a deadpan still of this proud list, donning familiar names like Estée Lauder, McDonald’s, Princeton University, and the City University of New York.13 Testimonials on their website praise Visage’s “fantastic technology,” “polite staff,” and “human approach,” across a facial-identification suite that includes tools from the more playful “eyewear try-on” to a vaguely austere “biometrics.”14 A telling litany of client case studies flaunts exciting, joyful, and futuristic images and language: “FaceDance Challenge: Using face as a joystick,” “McDonald’s Happy Studio: A virtual playground,” and even the cosmetic “Oriflame Makeup Wizard: Award-winning virtual makeup app.” They are innocuous and colorful enough that one just might gloss over the explicit endorsements of fascistic surveillance: “PROTECT: Biometric border control improves security and eliminates queues.” Now that everyone from Coca-Cola to the European Union is armed with pseudoscientific AGR biometric software, it is worth asking: Are we visible enough yet?

Screenshots of the Visage SDK website.

IV. “WE ARE YOU”

Staring at Visage SDK’s proud list of tech clients also conjured the world of my childhood, bringing me face to face with my own deep complicity. Crucially, my positionality troubles the dichotomy between watcher and watched: I write as a 1 percent / owning-class transfeminine member of the non-Black brahmin-savarna Indian tech diaspora,15 whose family has extracted extreme wealth from generational caste exploitation, tech, and venture capital.16 In cognizance of sociologist Satish Deshpande’s observation that dominant castes often assume a mythical castelessness, I would be remiss not to center my caste complicity given the vile continuities of brahminism and Islamophobia as sites of historical and contemporary surveillance. Cruel ancestral practices like that of the so-called breast tax (which coercively established the brahminical surveillance of Ezhava Dalit women’s bodies in what is now Kerala)17 have morphed into the modern-day harassment of Hijabi women in India (whose autonomy refuses the patriarchal entitlement of the brahminical gaze)18 and the proliferation of biometric monitoring within the 76-year-old brahminical occupation of Kashmir19 (powered by the biometric identification system Aadhaar in collusion with corporate actors like PayTM).20 Hegemonic immigration patterns have now exported these surveillant ideologies en masse to the wealthy echelons of Silicon Valley, where I was raised. At the same time, I wish to be careful to not produce a damage-centered framing of these histories.21 We have so much to learn in our “critical technology” classrooms and conferences from the day-to-day hacks, refusals, and worlds that have been, and are already, here—ever created by caste-oppressed, Kashmiri, and Indian Muslim communities, in spite of and beyond brahminical surveillance apparatuses. May we honor these stories, from the revolutionary life of Nangeli, an Ezhava woman who cut off her breasts in protest of the breast tax, to the Kashmiri reappropriation of death into “sacred necroresistance” on encrypted digital media platforms.22

As critical Muslim studies scholar Shaista Patel brilliantly reflects, “Complicity talk can bring the oppressor home and into the mirror”—no longer just an altar, but also a staunch reflection of my own participation in these systems of violence.23 Now, when I adorn myself in the mirror, her powerful words sit with me too—an invitation to abandon binary liberal narratives that overdetermine Western/savarna queer victimhood, refuge, and innocence and instead do the more difficult and nuanced work of accountability and reparation.24 In this moment of elite capture25 of queer/trans assertions via homonationalism, such insights call into question the merit of “POC” (“people of color”) or even “QTPOC” (“queer and trans people of color”) as useful shorthand to analyze surveillance at all, given the deep fractures of anti-Blackness, class, caste, and religion among racialized communities.

I am still learning how to ethically write about and sit in the space of my own complicity. I am learning, in community, how to unsettle my deep investments in the violently casteist, classist logics of surveillance—investments which are spiritual, psychological, and material (via family financial vehicles).26 Even in my most recent work, even in articles like this one, I notice the ways in which citing complicity has increasingly begun to feel quite routine and comfortable27—presenting (yet) another site for my/our own performances of guilt, refuge, and capital that are defanged from genuinely committed self-critique and action.28 It is in these moments that the mirror reminds me of my obligation to forever align myself with traditions of total treachery, subversion, and redistribution—what I see as inherently trans ways of moving through the world. In the words of my beloved friend manmit singh, “Transness resists capture, rejects coherence, and remains suspended in a state of instability and irreconcilability”—teaching us “to unsettle anti-Blackness, anti-Indigeneity, Islamophobia, [wealth hoarding] and brahminism through the destabilizing of one’s very existence”—that allows us to “end the world as we know it.”29

V. “WE GO AROUND YOU”

More than a decade ago, artist Adam Harvey released the C. V. Dazzle project—a documentation of the practice of anti-surveillance makeup, cosmetic looks that intentionally deploy saturated and cubist forms to evade biometric recognition.30 Taken up by makeup artists around the world, Harvey’s creative finesse also suggests rerouted modes of resistance to the ever-increasing project of trans (hyper)visibility. At its inception, the foremost goal of my project was to urge a reconsideration of the false promises of trans inclusion within the panoptic lens, given the brahminical, colonial, and techno-deterministic calculi of “visibility.” In this way, the enduring staged makeup shots perhaps dovetail well with avant-garde feminist/queer video art from the 1970 to 1990s. Many of these subversive pieces emerged against the backdrop of the crises of HIV/AIDS and the gendered chauvinism of a Western political class—for instance, Lydia Benglis’s Female Sensibility (1973), Valie Export’s Remote Remote (1973), Shigeko Kubota’s Video Poem (1976), Carolee Schneemann’s Up To and Including Her Limits (1976), Stephen Varble’s Journey to the Sun (unfinished), and Pattie Chang’s Fountain (1999)—all centered on the intention to reverse the (dominant) gaze.31 However, inspired by the beauty practices of Harvey, I am left wondering whether it is truly possible (or even worthwhile) to reverse the surveillant gaze. That is, perhaps an attempt to “watch the watchers” is not our only counter-praxis. Perhaps the piety and gravitas of making ourselves holy in the mirror, and nowhere else, is elusive and potent on its own.

Now, in my work and everyday life, I seek to offer an alternate understanding of trans life in its minutiae, in the smearing of a single stroke of mascara and the stain of an overzealous lipstick—rituals simultaneously so small and so infinitely meaningful that they resist legibility and capturability in their own right. In those private moments deemed unremarkable by the omniscient algorithmic eye, we speak multitudes and breathe universes—bending, twisting, and rewriting ourselves. May we “pay attention to the hijra,” as theorist Vqueeram Aditya Sahai urges, learning from their resilient glamor that “[t]rans beauty is rightly transcendental. It comes after the world has ended.”32 While we sit in (my/our) inescapable complicity and violence within the brahminical, settler-colonial, capitalist world order, may we also always remember that to be trans is to be treacherous. It is to be cryptic, to be Robin Hood, to paint our faces in the dark, and to always remember that a piece of the world—with all its biometric technologies, violent gazes, and right-wing surveillance states—dies in the quiet solitude of the mirror every day.

Indebted to Bhargavi Garimella, Gabi Maduro-Salvarrey, and Adrian Hackney for teaching me glamor and love; to Julie Mallozzi and Pauline Shongov for their transformative filmmaking pedagogy; and to manmit singh, Alexis Queen, Afiya Rahman, Eden Fesseha, Allanah Rolph & Maya Woods-Arthur for their undying support throughout this piece’s writing.

1. Reina Gossett, Eric Stanley, and Johanna Burton, eds., “Known Unknowns: An Introduction to Trap Door,” in Trap Door (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2017), xxiii.

2. @vqueer, Instagram post, September 2, 2020, https://www.instagram.com/p/CEoI_hJJWCb/?img_index=1.

3. Che Gossett, “Blackness and the Trouble of Trans Visibility,” in Gossett, Stanley, and Burton, Trap Door, 185–86.

4. Jasbir Puar, Terrorist Assemblages (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2007); micha cárdenas, “Dark Shimmers: The Rhythm of Necropolitical Affect in Digital Media,” in Gossett, Stanley, and Burton, Trap Door, 170.

5. Marlon Riggs, dir., Tongues Untied, 1989.

6. “Parametrically” here refers to the practice of staging different shots around a repeated motif, each with a (slightly) different angle.

7. Sarah Hennies, Contralto, 2019.

8. Bones Jones, “Queer Black Infiltration,” Logic(s), no. 19 (May 2023), https://logicmag.io/supa-dupa-skies/queer-black-infiltration/.

9. Andie Shabbar, “Queer-Alt-Delete,” Women’s Studies Quarterly 46, no. 3, 2018; Toby Beauchamp. Going Stealth (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2019); Mia Fischer, Terrorizing Gender (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2019); Jessica Hinchy, “Obscenity, Moral Contagion and Masculinity: Hijras in Public Space in Colonial North India,” Asian Studies Review 38, no. 2, 2014; Marquis Bey, Cistem Failure: Essays on Blackness and Cisgender (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2022).

10. Renè Kladzyk, “Policing Gender: How Surveillance Tech Aids Enforcement of Anti-Trans Laws,” Project on Government Oversight, 2023; Os Keyes, “The Misgendering Machines: Trans/HCI Implications of Automatic Gender Recognition,” Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 2018.

11. Of course, this was done with full, informed, and continued consent by myself and all of my chosen family, and I want to be careful to unequivocally state that I in no circumstance condone the usage of biometric software, especially nonconsensually, on footage of others. I am still sitting with the complexities of trying to make a point creatively without further endorsing, feeding into, and reifying these systems.

12. “Age detection software,” Visage SDK, https://visagetechnologies.com/age-detection/.

13. The list of clients powerfully testifies to the claims of Rodrigo Ochigame and others regarding the corporate capture of academia and the equal academic complicity in creating and funding surveillance systems. Rodrigo Ochigame, “The Invention of ‘Ethical AI’: How Big Tech Manipulates Academia to Avoid Regulation,” Intercept, December 20, 2019, https://theintercept.com/2019/12/20/mit-ethical-ai-artificial-intelligence/.

14. Visage SDK.

15. “brahmin” denotes the most powerful caste group in Indian society, while “savarna” is a term that connotes all members of (dominant-)caste society. I use the hyphenated term “brahmin-savarna” to reflect my own maternal and paternal ancestry (my father being Tamil brahmin and my mother being kaayasth—a dominant caste in North India).

16. “Class Distinctions and Income Brackets,” Resource Generation, https://resourcegeneration.org/breakdown-of-class-characteristics-income-brackets/.

17. K. D. Binu and Manosh Manoharan, “Absence in Presence,” Journal of International Women’s Studies 21, no. 6, 2021.

18. Izza Ahsan, “Hijab: Its Presence and Absence,” Indian Cultural Forum, February 25, 2022.

19. Huma Dar and many other Kashmiri feminists have made the incisive theoretical intervention of naming the Indian occupation in Kashmir an inherently “brahminical” one. Her work is foundational for all of us learning to write ethically on Kashmiri resistance. Huma Dar, “Dear Prof. Chatterjee, When Will You Engage with the ‘Discomfort’ of Indian Occupied Kashmir?,” Pulse (blog), September 10, 2015.

20. Stand with Kashmir, “Surveillance State on Speed: Now India Plans to Issue Unique IDs to Kashmiri Families,” Medium, January 16, 2023, https://standwithkashmir.medium.com/surveillance-state-on-speed-now-india-plans-to-issue-unique-ids-to-kashmiri-families-ecd8ba911b7e.

21. I am indebted to Eve Tuck’s lucid critique of “damage-centered research” for this reflection. Eve Tuck, “Suspending Damage: A Letter to Communities,” Harvard Educational Review 79, no. 3 (2009), https://pages.ucsd.edu/~rfrank/class_web/ES-114A/Week%204/TuckHEdR79-3.pdf.

22. Shaista Patel, “Talking Complicity, Breathing Coloniality: Interrogating Settler-centric Pedagogy of Teaching about White Settler Colonialism,” Journal of Curriculum and Pedagogy 19, no. 3, 2022; Dalit History Month, “The Ghost of Nangeli,” Medium, June 23, 2021; Umer Jan, “Sacred Necroresistance in India-Administered Kashmir,” Theoria 69, no. 170, 2022.

23. Patel, “Talking Complicity,” emphasis added.

24. Stand with Kashmir, “Surveillance State on Speed.”

25. Olúfẹ́úf O. Táíwò, Elite Capture (London: Pluto Press, 2022).

26. With many thanks to Resource Generation, an organization I have been grateful to be learning and growing from on my journey with wealth divestment and redistribution.

27. I am indebted to Dia Da Costa for this critique of “academically transmitted caste innocence.” Dia Da Costa, “Academically-Transmitted Caste Innocence,” Raiot, last modified August 24, 2018, https://raiot.in/academically-transmitted-caste-innocence/.

28. Shaista Patel, “Complicity Talk for Teaching/Writing about Palestine in North American Academia,” Critical Ethnic Studies (blog), June 3, 2019, http://www.criticalethnicstudiesjournal.org/blog/2019/6/3/complicity-talk-for-teachingwriting-about-palestine-in-north-american-academia.

29. manmit singh, “The Ally Must Die: A Trans Sikh Politics of Death and Unbodiment,” master’s thesis, San Francisco State University, 2023.

30. Lauren Valenti. “Can Makeup Be an Anti-Surveillance Tool?,” Vogue, June 12, 2020.

31. This radical strand of feminist filmmaking originates in early twentieth-century resistance to ethnographic cinema. See Fatimah Tobing Rony, The Third Eye: Race, Cinema, and Ethnographic Spectacle (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1996).

32. @vqueer, Instagram post, July 18, 2022, https://www.instagram.com/p/CgJkAiQvFKa/?igshid=YjVjNjZkNmFjNg==.