I grew up driving past rows of produce on California’s I-5 freeway, my focus on the horizon, where lines of crops disappear into a blue sky. At high speeds, the green spectacle is illusory, but slowing down brings the phantasmal mirage of green into focus. The agriculture sits still, almost captive, in militant rows, stretching to the limits of sight. The Golden State’s cornucopia is bursting at the seams, bloated with strawberries, almonds, pistachios, and all types of citrus. This agricultural machine relentlessly churns over a third of the country’s produce.

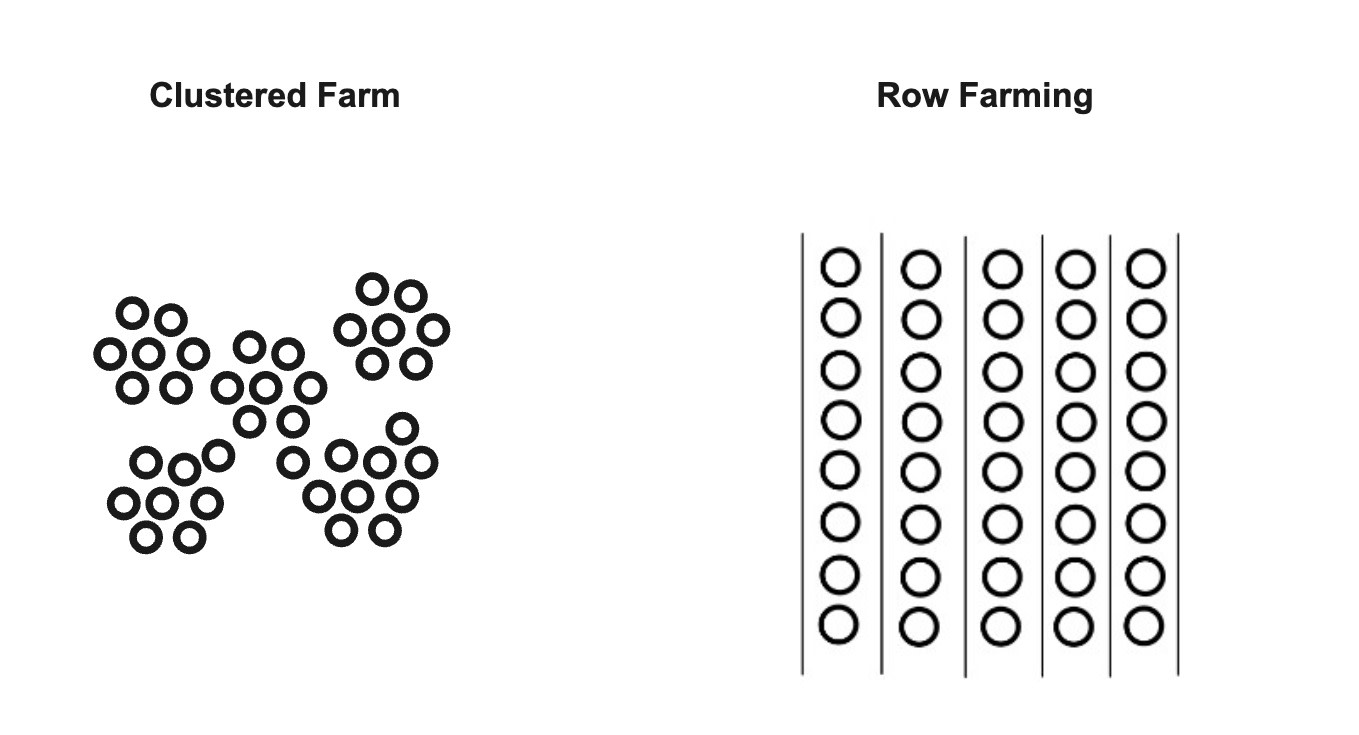

To the unfamiliar eye, a farm with neatly planted rows of seeds may appear clean or visually satisfying. But to the knowing eye, this segregation of seeds—separated by gender, age, and genus—displays a violent colonial logic driven by ownership, extraction, and optimization. Settler-colonial violence lays hold of all elements of life, beginning with its origins: seeds.

Seeds embody knowledge. They are nodes in networks carrying lineages of information that span continents and time. The way in which we plant seeds reflects our worldview. When we create space, we create meaning.

This essay is grounded in three examples of spatial networks that grow in scale: the farm, the village map, and the social networking platform. I begin with the personal, reflecting upon Palestinian diasporic farming practices within my own family, passed on through my Amo (Uncle) Abboud’s farm in California. I then translate how Amo’s approach to farming reflects how space in Palestine, specifically village trade routes, is oriented more broadly. Finally, I connect the physical to the digital, illustrating how Palestinians leverage commercial social media platforms to facilitate crowdsourced, peer-to-peer information-sharing practices.1 Overlaying the farm and the map against the digital networks reveals a vision and a practice of a connected “commons” in which decentralized sites of information and resource dispersal support the collective. As Palestinian land and life are asphyxiated, the relationships between trees on a farm, people moving through space, and group chats on social platforms comprise a Palestinian spatial politic—a continued way of life that we have always embodied, the creation of space amid fragmentation. In the following scenes, we move from seeds on a diasporic farm to nodes in a digital network, finding linkages that ultimately reveal a collective orientation toward reciprocity and a deep care for the land. Such connections blur the categorical separations between the diaspora and the homeland, the physical and the digital, high tech and low tech, past and present, ancestor and future kin.

A Palestinian spatial politic is a continued way of life that we have always embodied, the creation of space amid fragmentation.

Amo’s Farm

My Amo Abboud’s avocado farm in Southern California is a visual rupture from the symmetrical rows of industrial farms down the road. His home is surrounded by nine hundred thickly leaved avocado trees.

At first glance, Amo Abboud’s farm looks unkempt; weeds sprout freely through a blanket of fallen leaves. Trees are dispersed, growing in neither predefined rows nor lines. As a Palestinian farmer living in the diaspora, his approach to farming is “nontraditional” compared to the neighboring industrial farms. Amo takes a natural approach, carefully planting trees in clusters along the hillsides of his property.

“Trees are social creatures. We must listen to their needs,” he tells me. He speaks literally. Avocado trees are sensitive beings; their roots lie just beneath the earth’s surface, sprawling and intermingling. Their desire for closeness facilitates communication, as do Amo’s hands, which help nurture these networks. Young trees are deliberately planted next to older ones so they can distribute nutrients to one another, share the water supply, and, at critical moments, send defense enzymes in the event of an infection. In some parts of the farm, trees with different blooming times are planted together, encouraging one another to bear more fruit. However, this clustered orientation is not strictly output oriented. The fruiting of avocado is not a cumulative act of raw production but rather a celebration of a thriving community full of conversation.

The orientation of trees is just one of the equilibristics of Amo’s tending to the land. In the absence of pesticides and artificial fertilizers, life on his farm is wholly dependent on a network of support. He welcomes weeds and undergrowth to support the nectar-seeking pollinators who crave diverse flowers. “The tree’s baby leaves never lie.” The leaves speak to him about the state of the tree’s health: its vitamin deficiencies, the lack of nutrition in the soil, and even how long they suffered in the morning cold. The decomposing leaves on the ground, too, tell a story, indicating soil health. He saves the fallen leaves, composting them into soil. Underneath the weeds, the soil is fresh and rich, like spent coffee grounds. Amo tells me, “I am in a perpetual conversation with Mother Nature and the land.” Despite the physical distance between California and Palestine, the configuration of Amo’s farm resembles the clustering of olive trees that trace the Palestinian hills.

Clustered and Connected: Historical Trade Routes

When driving through the West Bank of Palestine, it becomes clear who stewards the land. The landscape tells the story. Ancient stone terraces that contour the Palestinian hillsides support clusters of olive trees, displaying the care of Palestinian farmers who have climbed these hills and tended to their trees for centuries.

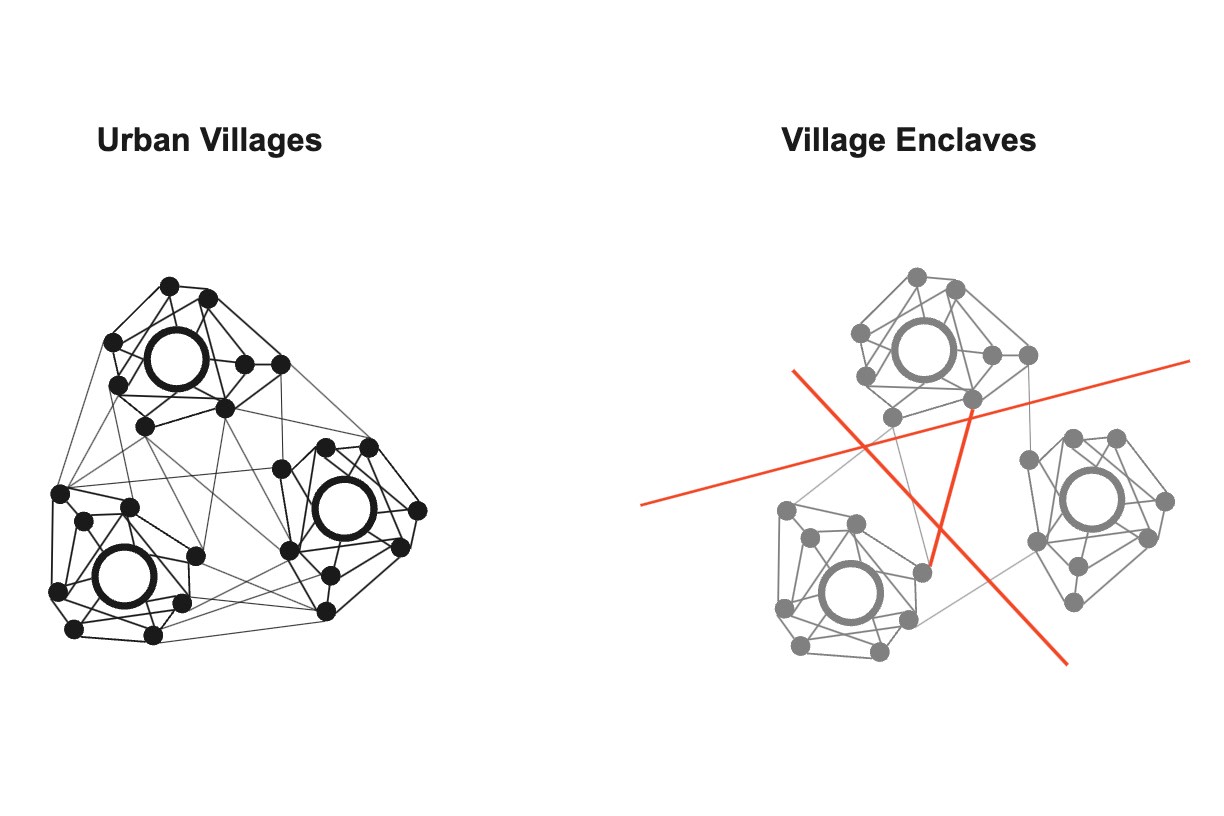

This clustering of trees demonstrates how space in Palestine is conceived. An aerial view of Palestine’s historic landscape during the Ottoman Empire (1516–1917) reveals a webbed network of local pathways that sustained trade between urban centers and rural villages. A system of paths connected interior Palestinian urban centers to the southern coastal plains, offering a land bridge between Asia, Europe, and Africa and complicating the “universal” urban- versus-rural bifurcation. The city of Nablus in particular served as a vibrant economic and cultural hub, allowing for complex social networks to form.

Nablus not only has access to water but also fertile soil and hilly terrain. The conjoining routes brought people, traders, and information. The economy of Nablus was robust, consisting in a culture of commerce rooted in familial ties and allegiances. When Nablus was under siege in 1771 and 1773, it resisted; fifty years later, in 1831, it withstood the military occupation of Greater Syria due to its network of sprawling trade routes. Nablus’s enmeshed roots function like the root system of Amo Abboud’s avocado trees: clustered and “social,” they facilitate the sharing of information and create a network of support strong enough to resist attacks.

Today, Israel’s constructed environment not only sustains its military occupation but also its weapons. Palestinians living inside the West Bank, East Jerusalem, Gaza, and within the 1949 Armistice Line (known as the Green Line) experience vastly different layers of spatial mobility. Walls, checkpoints, fences, and highways snake throughout the land and create a patchwork of enclaves, an attempt to sever social and economic connections and foreclose upon the most basic human instinct of social connection. As Israeli roads and walls fragment the landscape, Palestinian trade networks hold a resilient history of connectivity. Academics such as Fida Yaseen propose that a return to these urban village networks would allow for resilient spatial planning that could help Palestinians resist and withstand Israeli sieges. Decentering cities as primary hubs of communication would allow villages to communicate more freely with one another. Yaseen describes this horizontal communication as a “return” to autonomous ruralism sourced from precolonial Palestinian trade networks, which she terms “the urban village.”

As these historical trade networks are no longer available to Palestinians, digital networks offer new means of relational connection. Palestinians’ digital networks are a continuation of resilient survival rooted in a network of collective care.

A Network of Care

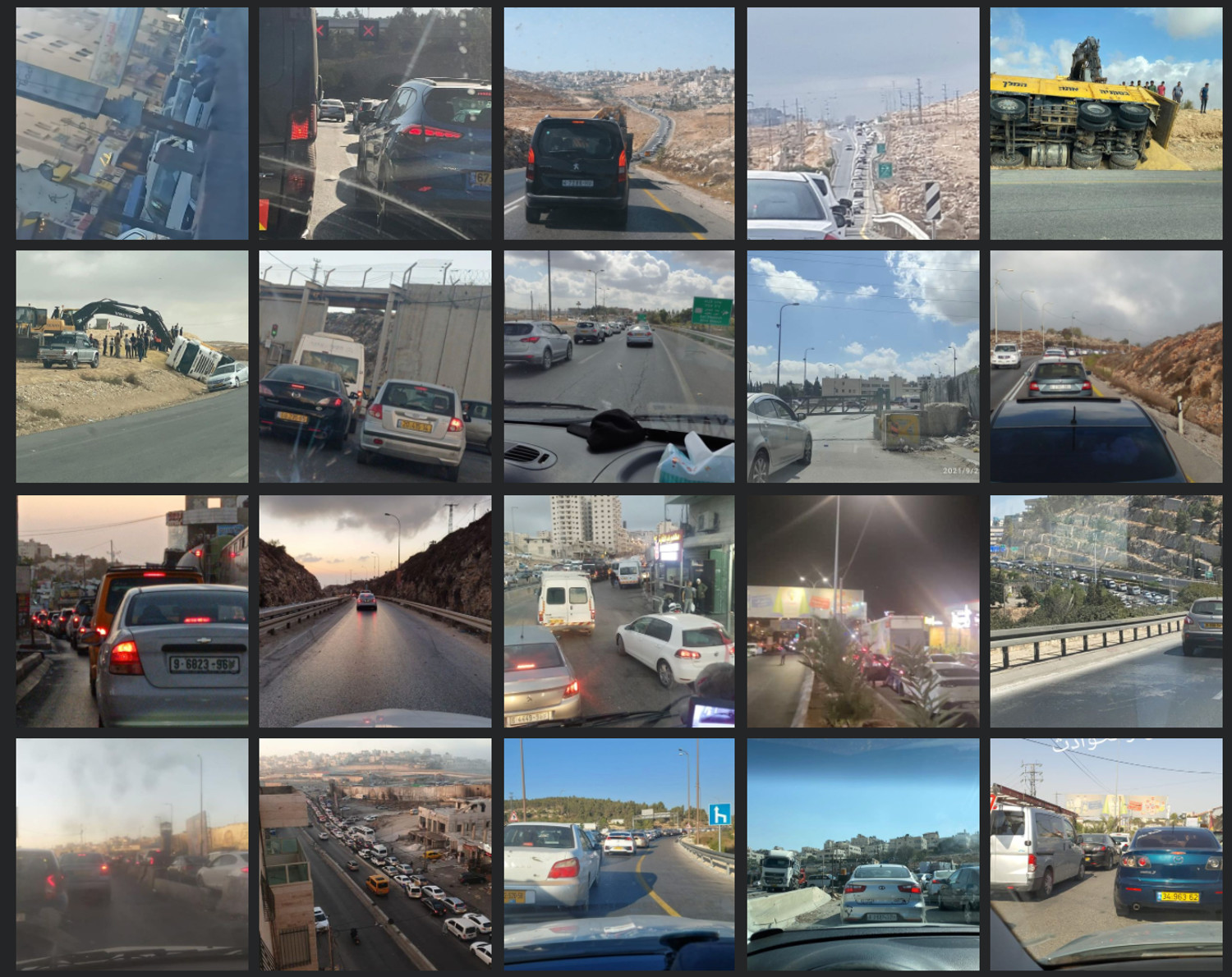

July 2022, I am on the road from Nablus to Ramallah. As we approach a line of brake lights, the taxi driver checks WhatsApp: a collision ahead, two cars collided, could be fatal. I settle into the back seat and turn my gaze to the rows of produce outside my window. I catch myself holding my breath.

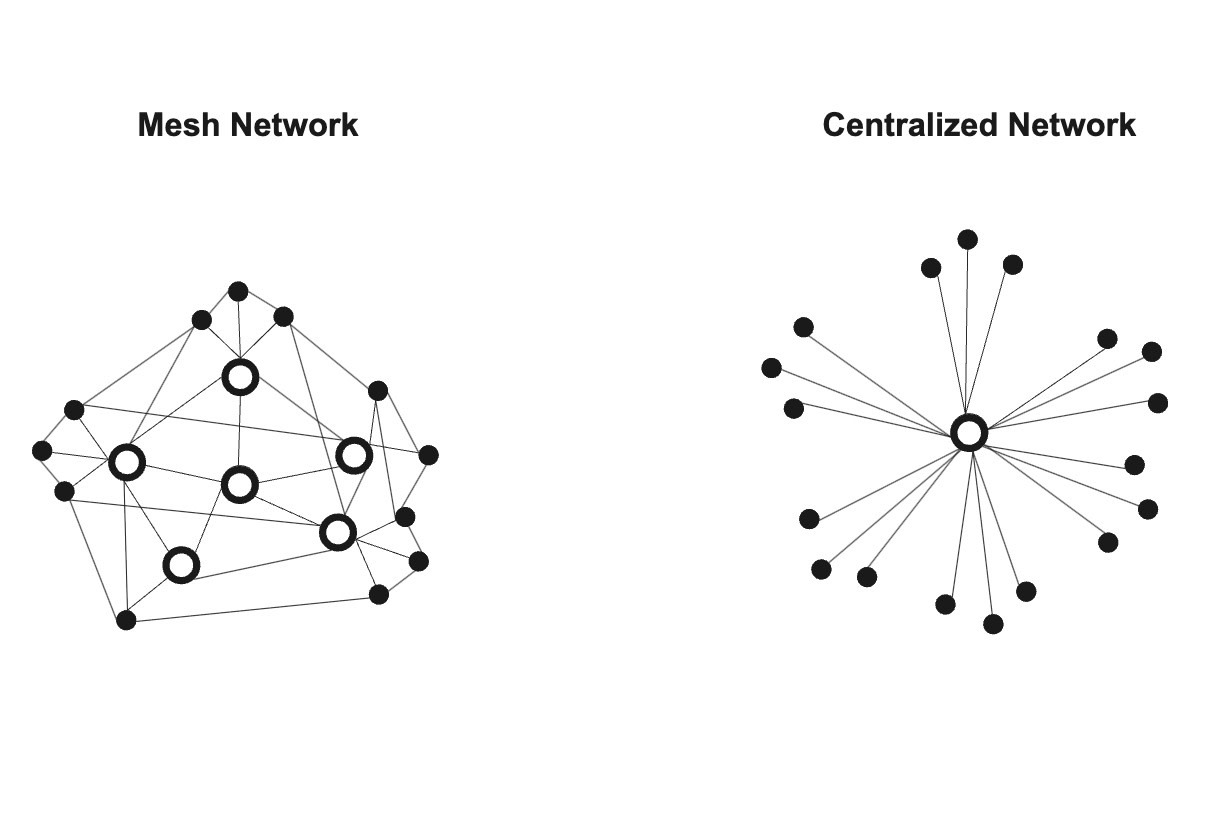

Movement in Palestine is relational. Information about ever-changing road conditions forms a critical meshwork that allows Palestinians to navigate their world. Like the urban village networks, where village “nodes” connect to one another without going through the city center, a mesh network forms a digital topology in which infrastructural nodes connect directly and nonhierarchically.

Amahl Bishara describes how, when occupying Israeli forces restricted Palestinians’ physical movement during the Second Intifada (September 2000), cell phones and radio broadcasts helped create a “network of care” through which Palestinians communicated both on and off the road, sharing critical information to promote safety and to “rally against a politics of isolation” through peer-to-peer connections. Israel’s immobilizing infrastructure across Palestine continues to make movement burdensome, unpredictable, painfully slow, and, often, dangerous. Today, a digital “network of care” exists on social media platforms; apps such as Facebook and WhatsApp are the primary methods for sharing safety information when traveling between cities, crowdsourcing and distributing mutual aid, and disseminating information during surges of violence.2

Israel’s assault on the physical landscape of Palestine is a blueprint for its ongoing assault on Palestinians’ digital mobility. Digital communication among Palestinians, including their group chats on Facebook and WhatsApp, are subject to a web of “invisible” digital borders that restrict cellular data, surveil conversations, and deplatform accounts.3 Moreover, Meta has shared information from “private” messages with the Israeli army, leading to the arrests of Palestinians and the destruction of their homes. This web of restrictive high-tech and low-tech infrastructure constitutes what Helga Tawil-Souri calls a digital occupation. The spatial politic formed by Palestinians around collective digital networks allows them to use Facebook and WhatsApp to not only resist but also to subvert the digital borders imposed upon them by various proprietary technology companies.4 These digital commons are a critical vehicle for Palestinians building digital networks of care. They are connected to a longer history of how Palestinians have always navigated their way through space by rooting themselves in social connections and prioritizing the collective interests of the group over the individual.

Facebook groups such as “Conditions of Roads and Checkpoints between Palestinian Cities” bring Palestinians together in a digital space where thousands of people disseminate real-time updates about border crossings, checkpoints, traffic conditions, settler violence, and military movement along the roads. Similar to the clusters of trees and connected village routes, Palestinians’ use of digital communication relies on a decentralized network of dispersed yet connected nodes that allow for social (peer-to-peer) connections.

Even in the digital realm, the physical landscape grounds these tactical conversations. Posts consist almost entirely of visual content; Palestinians routinely share images of roads unaccompanied by geographic locations, street names, or geospatial information, relying on a shared visual culture and intimately detailed knowledge of the physical landscape. Community members draw upon their perceptual knowledge to decipher locations based on visual cues such as the contour of the landscape, the architecture of the checkpoint, or the style of construction on a road.

As in the case of Amo Abboud’s trees and their commingling roots, interdependent webs of social connections foster the sharing of information. Individuals join various group chats that pertain to their specific routes, governorates, and villages. The ability to see others’ profiles, full names, villages, and mutual friends becomes a method of vetting information. While platforms like WhatsApp do not reveal as many aspects of a user’s identity as Facebook does, the content they post can provide a different set of social cues; an individual’s visa status, job, identity papers, or residency may be discernible based upon which checkpoints they pass, which roads they drive on, and how they move through space. Mutual connections also function as subnetworks for specific navigation routes, and posts provide windows into social networks based on governorates, driving patterns, friendships, and familial relations.

Sharing information through these networks is not just a safety tactic developed in response to settler-colonial control but serves as a continuation of culture, community, and historical knowledge that decenters the individual and prioritizes the collective interest of the community. These networks affirm the way Palestinians have always and continue to cultivate life, despite the ongoing Nakba.

Asphyxiation of Space

As various nodes of Palestinian land and life come increasingly under attack, it becomes clear that the violence of Israeli occupation, too, is intentionally fractural. In its targeting of Palestinian seeds, criminalization of farming practices, and restriction of access to digital communication, Israel’s systemic suffocation of Palestinian land and life constitutes what Sari Hanafi terms spacio-cide: “the assault on the space, whether it is a built/urban area, landscape or land property.”

Israeli settlements target the most fertile places for agriculture, cutting off Palestinian farmers from access to their lands. Land is asphyxiated on all fronts; crops are poisoned with toxic chemicals, and settlements dump their waste. Foraging practices are criminalized in the name of “conservation” and “preservation.”5 Scarce water sources needed to irrigate the land are sequestered and cut off. Building new water wells is illegal, too. Settlers routinely arrive with bulldozers, destroying Palestinians’ crops and burning trees, and pour concrete down water wells. Predictably, violence increases during the annual olive harvest as Palestinian farmers tend to their trees. In villages outside of Ramallah, Israeli authorities erect fences and gates, obstructing farmers from accessing their land; the farmers are required to apply for elusive military permits and wait by the side of the road, hoping an IOF (Israeli occupying forces) vehicle passing by will be so kind as to let them in. Absurdity is the tool by which Israel tills Palestinian soil.

For the plant life that nonetheless resiliently sprouts, Palestinian farmers are confronted with market manipulation, forced to compete against heavily subsidized Israeli agricultural products. As farming itself is a game of survival, traditional farming practices suffer to the point of extinction, and entire lineages are systematically wiped from the earth.

The Depth of Israel’s Violence Extends Far Deeper than the Topsoil

Spacio-cide works in tandem with green colonialism, which seeks simultaneously to asphyxiate Palestinian land and to offer hollow, artificial growth, appropriating the landscape while burying any trace of Palestinian life. For example, in 1924, Israel started importing avocado trees from California; today, they are Israel’s largest fruit export. As Amo, displaced from his homeland in Palestine, tends to avocado trees native to California, the same fruit is weaponized to suppress traditional Palestinian farming practices. There is a layered irony in planting life that belongs to one land while being uprooted from another.6

Eucalyptus and pine trees are also telltale signs of Israeli presence in Palestine. They offer a visual alert, specifically in the West Bank, that an Israeli settlement is nearby. These trees, like the people who planted them, are not indigenous to the land, and their importation brought invasive species to Palestine, with catastrophic consequences. In the early 1900s, Zionist settlers attempted and failed to plant olive and fruit trees, as the trees required gentle care and knowledge of the land they did not possess. Unable to speak to the land, the settlers attempted to change the land’s language.

During the 1920s, settlers switched to importing pine and eucalyptus trees, primarily from Europe. Funded by the Jewish National Fund, pine trees were planted in haste, used to effect a propagandistic agenda: first by concealing the remains of destroyed Palestinian villages, and second by “Europeanizing” the natural landscape by “making the desert bloom.” Desperate for water, the trees leeched onto the land, and Israelis planted them at a rapid pace to keep up with and conceal their rapid destruction of Palestinian villages. Today, protected parks, “national” forests, and nature reserves like “South Africa Forest” and “Canada Park” sit atop the destroyed villages of Lubya, Beit Nuba, Imwas, Yalu, Ijzim, Umm al-Zinat, Khubbaza, Yalo, and countless others. These green graveyards also kill the life surrounding them; eucalyptus and pine trees hoard nutrients and water, and their acidic leaves prevent undergrowth. After depleting the soil, they often erupt in flames, unable to withstand the glare of the desert sun. The trees themselves are settlers.

Unable to speak to the land, the settlers attempted to change the land’s language.

The pines planted by the Israelis took on an imaginational quality; they functioned to “Europeanize” the landscape, furthering the Western idea of a “proper forest” in Zionist imagery. Ghada Sasa calls out the two-faced connection between conservation and protection as a strategic tactic to force the connection between the People of Israel and the Land of Israel. The 250 million trees that have been planted since 1948 exemplify just one form of “green colonialism” designed to remove the presence of Palestinians from their land and deny their right to return.

From the kin of spacio-cide and green colonialism emerges a monoculture, fueled by notions of hegemony and supremacy. This recalls industrial farms in California, where farmers, fearful of cross-pollination, shroud miles of trees in plastic netting to “protect” their cash crops from friendly pollinators.

Absurdity grows in abundance, and its produce is exported around the world. As Paola Federica Di Paolo argues, observing the context of agriculture in India, a monoculture of crops not only destroys the soil but also “human life and a sense of social belonging by destroying the social network by which seeds have been developed and distributed for generations.”

Sowing a Network

Palestinian stewardship of the land continues to cultivate resilient networks that, like seeds, expand into the diaspora and transgress the unnatural constraints of national borders. The world is now mobilizing to spread information about crowdsourcing resources, engage in collective boycotts, and share safety resources with their communities. This web of horizontal communication is evidenced by the comments on Instagram posts in which people worldwide offer Palestinians in Gaza advice on starting gardens in order to survive the manufactured famine. How do you grow seeds in hot desert sand? The collective is at the heart of this question, and its answer nourishes Palestinian liberation.

A relational approach to sowing seeds can orient a world. Farming practices in the Palestinian diaspora, historic Palestinian village networks, and contemporary Palestinian digital communication practices all exemplify the importance of reciprocity and the utility of spatial connections and embodied knowledge.

A relational approach to sowing seeds can orient a world.

Palestinian conceptions and spatial imaginaries are more than sites of resistance or survival against settler-colonial asphyxiation; they are a relational praxis in their own right. Horizontal communication weaves us together across violently imposed distances, connecting a people to their land, seeds with their ancestral roots, and historical trade routes with digital data clusters to historical trade and communication routes.

Seeds are nodes of information, data points throughout the many layers of resilient spatial networks that Palestinians have always relied upon to maintain their communities and autonomy. The global echo of colonial resistance in land-cultivation practices reverberates in the efforts of groups like the Indigenous Seed Keepers Network, in which Rowen White of the Akwesasne Mohawk fights for interspecies kinship and to protect Indigenous seeds from biopiracy, or in the work of the Palestine Heirloom Seed Library, a project that aims to collect, distribute, and conserve traditional Palestinian seeds across the diaspora. Vivien Sansour, organizer of the Palestine Heirloom Seed Library, says dispersing these seeds “symbolizes the freedom we hope to achieve ourselves … If we can’t fly, our seeds are flying, and they are the teachers, not us.”

Amo Abboud was only four when our family fled violence in 1967. “How did you learn to farm?” I once asked him.

“Some knowledge falls off, I pick it up, and I keep it, and that’s how I learn.”

1. Academics in various disciplines may classify these networks as: “webs of life” in the field of ecology, “social networks” or “peer production” in internet studies, “mobile commons” in transportation studies—the list goes on. However, as Tim Ingold notes, these disciplines assume a separation between elements are inherently connected. In line with Ingold, this meditation on Palestinian spatial relationships stresses the importance of a “betweenness,” a mutuality, a “mesh-work,” where the relation itself is the connection.

2. Alice Arnold links Bishara’s “network of care” to Facebook groups about traffic.

3. The web of “invisible” digital borders extends into the diaspora as well. 4. I am cautious of imbuing these networks with too much subversive or “liberatory” capability. These networks do not displace settler-colonial restrictions on movement, nor do they operate in a vacuum free from discrimination by technology platforms themselves.

5. The Israel Nature and Parks Authority (INPA) has prohibited the collection of three prominent Palestinian herbs: ’akkoub (Gundelia tournefortii), za’atar (Majorana syriaca), and miramiyyeh (Salvia tribola). Since 2005, picking ’akkoub was made illegal by the Israeli authorities.

6. The rise of Palestinian farmers growing avocados is a result of strategic tactics that aim to suppress traditional Palestinian farming practices while simultaneously fueling Israel’s agriculture economy..