When I was informed that my daddy’s cancer bore hereditary implications, I was no longer caught in the preceding months’ loop of anxiously catastrophizing about paternal mortality. I was devastated when my mother first told me that my daddy was sick, wracked with uncertainty before his surgery, relieved following its success, and then terrified to learn that the castration-resistant prostate cancer had lingered in his lymph nodes and would require thirty-five sessions of radiotherapy (every weekday for seven weeks) and a subsequent two years of hormone therapy.

I was uncomfortably forced to shift registers—to transmute my filial affection into the calculations of biologized kinship and the statistics that constitute enumerations of population and risk. Beyond how the sexed anatomical specificity of prostate cancer would affect my brother, genetic counseling would reveal whether I also had risks to consider. Although a friend of mine has forbidden me from over-citing Susan Sontag, I can’t help but think about how she describes the therapeutic benevolence of withholding diagnoses from cancer patients: that because, for many, cancer simply equals a death sentence and “the truth will be intolerable to all but exceptionally mature and intelligent patients,” the majority of people must be protected from the jarring confrontation with the unpredictable inevitability of one’s own mortality. A methodology of terror management, if you will.1 But the severity of my father’s cancer, far from humanely anesthetizing him from the devastating psychic and emotional consequences of such revelations, had been obscured from him and from us all through the lapsed or withheld communication characteristic of medical racism: he learned on his own—unexpectedly, during an unextraordinary appointment for hormone therapy, and from someone other than his oncologist—the gravity of his condition.

While my parents’ immigrant success offered me the possibility and opportunity for an autobiography of upward mobility, such medical racism was a reminder of the antiblack ceiling that looms over and orders our worlds—even for those of us who ought to transcend and no longer deserve its indignities. Once again, as in the past, my black African family was stripped to its constituent parts: to mere blood association. My daddy became a paternal carrier-potential disseminator of cancerous genes; my beloved older brother became my father’s second at-risk offspring; and my mother, my father’s supportive caretaker. The clean borders of my father’s prostatectomy metastasized to become comfortably imbricated in the Westphalian ones. The family is simply an enumerable population; family becomes a surveilled demographic in a carceral state.

The Patient-Citizen

The very first sentences of Sontag’s Illness as Metaphor describe health as a kind of Westphalian choreography of border-making: that “everyone who is born holds dual citizenship, in the kingdom of the well and in the kingdom of the sick,” and that “although we all prefer to use only the good passport, sooner or later each of us is obliged, at least for a spell, to identify ourselves as citizens of that other place.” As soberingly correct as she is that our resilient and fallible bodies will all, someday and in some way, find themselves ailing, she is also very wrong.

David Armstrong’s sociological conception of surveillance medicine begins by narrating Polish medical historian Erwin Ackerknecht’s periodization of medical provision from the seventeenth century to the present. The history proceeds from library medicine’s prioritization of physicians’ classical learning to bedside medicine, which stressed disease etiology and symptom management, and eventually hospital medicine (or pathological medicine) condensing into a more dominant paradigm with the creation of Parisian hospitals at the end of the eighteenth century. Advancements in clinical investigations and diagnostic technologies led to a spatialization of illness within the cartography of the body and ushered in a new subperiod of laboratory medicine at the end of the nineteenth century. But the axes of symptom, sign, and pathology, per Armstrong, were reconceptualized in the early twentieth century, as “illness beg[an] to leave the three-dimensional confine of the volume of the human body to inhabit a novel extracorporal space,” initiating the new and present moment of surveillance medicine.

Against Sontag’s regime of dual citizenship, surveillance medicine obliterates discrete and binarized notions of sickness and health upon the exit from the hospital of the sole management of pathologies. Surveillance medicine’s “problematization of the normal” brings everyone under the governmentality of biomedicalization and transforms the body into a spectrum of perpetual unhealth, from preemptively to acutely pathological. Surveillance medicine describes not only an extra-institutional space but a social imposition that transforms people into vigilant populations whose poor health reflects their moral failings. One’s poor health demotes them into bad citizenship, reiterating the carefully delineated Malthusian and social Darwinist cartographies of race and class within and between the so-called global North and South, the narrated responsibilities for the individual’s and the world’s degradation, and assessments of whose lives are worth living.

Surveillance medicine describes not only an extra-institutional space but a social imposition that transforms people into vigilant populations whose poor health reflects their moral failings.

In surveillance medicine, risk is a critical variable because, in epidemiology and other fields, it quantifies the probability of some ill health or disease outcome. While health is most responsibly assessed through a cluster of social determinants—class / socioeconomic status, race and gender, social safety nets, income and job security, zip code, vulnerability to violence, and so on—risk is too often conceived of as a direct result of one’s behavior, or even cruder identitarian assessments. Fatness and diabetes indicate slovenly carelessness with one’s diet; HIV positivity, the innate promiscuity associated with gay manhood or trans womanhood;2 and you have sickle cell anemia, frankly, because you’re black.3

Essentializations of identity (both in genetic predispositions and moral presumptions regarding care for oneself and health-related behaviors) have dangerously translated into racially calculable risk assessments. For decades, physicians have used race-corrected algorithms to make medical decisions—most of which, for black people, tend to end up delaying often life-saving or -prolonging medical treatments because the threshold for intervention is drastically raised with these black/white corrections. For example, there’s a race correction in the American Heart Association’s “Get with the Guidelines—Heart Failure Risk Score,” which predicts in-hospital mortality for patients with acute heart failure. Three points are added to the calculation if a patient is black, which increases their estimated probability of death, but this addition also yields a lower risk baseline for black patients, thereby raising the threshold for clinical intervention.

Most famously, race-corrected estimations for glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), a calculation for kidney filtering and function, report higher eGFR values and suggest better kidney function in black people—who were believed to have more muscle and higher levels of creatine—translating to a lower baseline for renal failure. This, in turn, leads to delays in referrals for black patients to nephrology specialists or eligibility for kidney transplantation. In a 2020 study of the Mass General Brigham health system that analyzed 57,000 health records of people with chronic kidney disease (CKD), one-third of the 2,225 black patients, 743 people, “would hypothetically be reclassified to a more severe CKD stage if the race multiplier were removed.” In 2022, the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network, which connects transplant lists to patients, banned use of the calculation and announced a change in the waiting times for black transplant candidates: in July 2023, six months after the policy change, more than 6,000 black kidney patients, along with over 500 additional candidates with modified waiting times, were able to receive transplants.

There’s no algorithmic calculation for prostate cancer treatment, but the complementary gesture is delayed screening—owed, perhaps, to black men’s ignorance about, inability to afford and barriers to, apathy against, or anxiety toward actively seeking or receiving preventative care. Prostate cancer is diagnosed through a rectal exam or a prostate-specific androgen (PSA) test; while testing healthy cisgender men without symptoms may be controversial, semi-regular testing for men over the age of fifty is a norm. Testing for black men is even more urgent because of increased risk factors: black men often develop the cancer at a younger age, and often in a more aggressive form than white men. My daddy is comically hypervigilant about medical screenings; his previous nonwhite doctor was adamant about regular PSA tests, but his new white physician was not. Daddy insisted on a blood test and was found to have massively elevated PSA levels, which indicate prostate cancer. I don’t want to think about what would have happened to him if he hadn’t insisted, but medicine’s discriminatory disregard toward black vigilance (often written off as needless paranoia) and the resultant delay in routine medical examinations has an influence on their mortality outcomes because of the seriousness of an illness at the eventual time of its detection.

My father was a bad patient—he ignored the advice of his advising “medical expert”—but he was sufficiently vigilant about his health and might have saved his own life: he’s a good citizen.

The Patient-Inheritor

Risk, one can responsibly conclude, is a hereditary fabrication masquerading as an inevitability: a structurally produced condition of vulnerability that nevertheless seeps into your bloodline as a justification of its inferiority, marginality, impoverishment, deprivation, or other necropolitical designation. Its calculability extends to the battlefield. If surveillance medicine transforms family units into populations responsible for their health and safety, what does this mean for the minoritized or colonized family under the thumb of the state?

Golda Meir, a founder of the State of Israel and its fourth prime minister, famously pronounced that “peace will come when Arabs love their children more than they hate [Israelis].” The pathological and hereditary Palestinian condition, the defining “anti-Semitic hatred” that Palestinian parents allegedly pass down to their children—no matter what images of wailing or catatonic mothers and fathers tenderly holding their limp and bloodied children illustrate otherwise—predisposes them to death by Israeli snipers, apartment-block busters, and rapidly precipitating famine. Entire families in Gaza have been eliminated from the civil register for failing to adhere to the contradictory and genocidal demands of a settler-colonial occupation that casts their identity as a devious security threat. While the mother is the bearer of life, it is through the father—the fighting-aged would-be terrorist of Zionists’ nightmares—that Palestinian violence is actualized: a Freudian phylogenetic bestowal and inheritance of a predisposition to brutality. Lamarckian inheritance, the idea that an organism could pass on physical or psychological characteristics to its offspring, has mostly been debunked by Mendelian and other principles of genetic inheritance and hybridization. But what endures is the desire to ascribe a persistent essential character, whether through spurious descriptions of the transgenerational epigenetic passage of trauma or the racial essentializing of Orientalism.

If surveillance medicine transforms family units into populations responsible for their health and safety, what does this mean for the minoritized or colonized family under the thumb of the state?

To fully disarm the threat, military logic goes, is to strip naked and sexually humiliate it: to feminize it. Israeli torture of Palestinian men famously includes a targeting of their genitals, a trauma that can subsequently produce sexual dysfunction, including the “fear of or aversion to sexual activity.” This is a debasement and attempted foreclosure of Palestinian fatherhood—a demographic notably absented from global humanitarianism’s gendered focus on the sexual innocence of women and children (and imperial feminism’s impulse to save said women and children from their barbarous men). This surveillant biomedicalized regime of population management binds together these men through the colonial anxiety of racialized masculinities that annihilate patrilineal networks.

Surveillance medicine collides with the Israeli control system as a damnation of Palestinian life and as a condemnation of their noncitizenship and nonbelonging in the settler-colonial vision of futurity. Between the impossibility of obtaining a permit to leave Gaza to seek treatment outside Palestine and the complete destruction of Gaza’s medical infrastructure, the fate of Palestinians receiving cancer treatment (for example) has become unspeakably dire. They are stranded far from home, unable to return; they die in incarceration (as in the case of medically neglected and terminally ill Walid Daqqa, a writer and former member of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine who continues to be detained even after his death); or they die in the process of their hospital wards being attacked, forcibly evacuated, and eventually turned into mass graves by the Israeli forces.

If the state is a nationalization of identity, a congruence between the shared community of the nation and the territoriality of state borders, then the regulation of population attaches itself to the demographic desires of a given Westphalian project. What brings together the black American family in the United States and the Palestinian family in Palestine is the state’s investment in their respective destruction, the elevated production of risk, and the calculable increase in the likelihood of mortality, “natural” or otherwise. To acquiesce to one’s own death is to perform good citizenship, to respect the state’s logic of management and its enactment of the Darwinian natural order. Ironically, to refuse annihilation is to have a death wish and to accept the targeting of one’s own body and one’s community as retribution by the state.

What brings together the black American family in the United States and the Palestinian family in Palestine is the state’s investment in their respective destruction, the elevated production of risk, and the calculable increase in the likelihood of mortality, “natural” or otherwise.

The Patient-Border

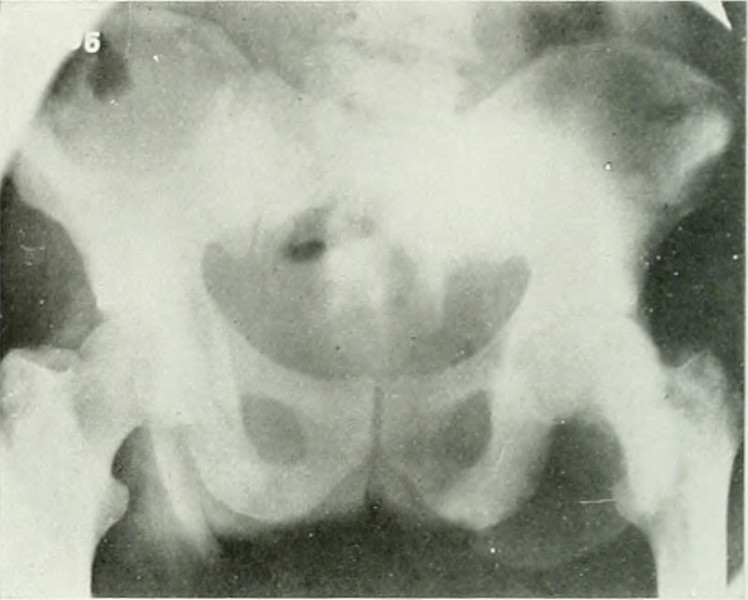

After some time into his recovery from the depleting and debilitating side effects of his radiation therapy, my father began genetic counseling. Or, rather, the part of our nuclear unit defined by patrilineal consanguinity began genetic counseling. My father had his blood tested to look for mutated genetic markers that indicate elevated risk for disease or illness. Daddy had an especially aggressive grade of prostate cancer4, which places my brother at potentially elevated risk for testicular cancer, both of us at increased risk for pancreatic cancer, and me at potentially elevated risk for breast and ovarian cancers.

Loving my dad and feeling a tremendous relief that he’s recovering is coupled with a deeply unsettled Oedipal resentment for his entirely too on-the-nose gift of quite literally poisonous blood. But after the passage of another Father’s Day with him, still alive against the unfathomable grief and loss and death of so many daddies in Palestine, I’ve come to better understand bell hooks’s conception of love as the only cure for the fascistic fear of and obsession with death. Loving my daddy through cancer is a love guided by an open and unselfconscious grief that alchemizes into a refusal of temporalities of appropriate sadness. “Love invites us to grieve … as a ritual of mourning and celebration,” hooks writes. This love-grief binds together our personal with the global political in a refusal of solipsistic particularism, one that reinforces our singular identitarian selves and the borders that define and dictate our conditions.

The family contains the body-territory of fatherhood as a biological relation, but an affect of paternal love and care (i.e., care by and care for fathers) yields a resistant and obliterative frame of anti-carceral kinship. Walid Daqqa may have died in the “place without a door,” but his daughter Milad (whose name means “birth” in Arabic) and scores of other Palestinian children were born because he and other incarcerated men were able to smuggle their sperm beyond the Israeli prison walls that confined them. These children are called “ambassadors of freedom,” and their conception and birth are refusals of the criminalization of life itself: a politic of fatherhood that reunites Palestinian daddies and children at the borders of life and death. We reject the sovereignty of these state impositions and their necropolitical predeterminations as we produce our ethics of love; we destroy these borders to fully love our dads and to rescue our fathers.

1. Terror management is a social and evolutionary psychological theory describing the self-preservatory instinct through which anxiety over mortality salience is managed, and the techniques of literal (e.g., an afterlife in which the soul lives on beyond the body) and symbolic (e.g., a lineage and legacy that transcends the fragile body) immortality.

2. Because receptive anal sex is a behavior with some of the highest risks of HIV transmission and associated with the queer male communities that HIV has devastated, the category of “men who have sex with men” (MSM) was deployed to capture HIV risk associated with sexual behavior. But because of its focus on anatomy and sex acts, trans women are also captured within this category. Beyond its inherent misgendering, the category also fails to accurately describe how trans women’s vulnerabilities to HIV are not simply a result of sexual behavior but also their navigations of social exclusion and discrimination because of their womanhood.

3. Said sardonically, of course. While sickle cell anemia is understood in the Western world as a black illness (it was endemic to southern Europe until its eradication in the mid-twentieth century), it is prevalent in tropical regions, and its global distribution is related to the frequency of malaria. Thus, its prevalence is not simply in West and Central Africa (and associated diasporas) but also in a latitudinal band extending across the Mediterranean region, India, and parts of the Middle East.

4. The Gleason score for grades of prostate cancer describes the resemblance between normal cells and cancerous cells. Grade 1 cells resemble normal prostate tissue, whereas grade 5 cells are so cancerous and mutated that they no longer look like normal cells. The Gleason score ranges in theory from 2 to 10, but 6 to 10 in practice; 6 or lower is low grade, 7 is intermediate, and 8–10 is high. My father’s score was a 9.