Oliver Rollins is an assistant professor in American ethnic studies at the University of Washington. In his sociological research, he explores how racial identity and racialized discourses engage with, and are affected by, the production and use of neuroscientific technologies and knowledges. In his book Conviction: The Making and Unmaking of the Violent Brain (Stanford University Press, 2021), Rollins traces the development and use of neuroimaging research on antisocial behaviors and crime, paying special attention to the limits of this controversial brain model in dealing with aspects of social difference, power, and inequality. This conversation begins with the book’s findings and further interrogate the logics of race, capital, and the military that shaped this predictive science concerning the biology of violent behavior. Neurocriminology, much like all science, does not happen in a vacuum; social, political, and economic structures restrict and enable this field. While locating the funding sources for neurocriminology research help us make sense of the field’s priorities, questioning its ties to previously established forms of racial sciences such as eugenics leads us to a more fundamental question: Why does the US academy invest so much capital in the flawed scientistic endeavor of locating biological roots of violence?

Sucheta Ghoshal: In your book Conviction, you guide the reader toward an understanding of the neuroscientific impulse to explain and fix violence. More broadly, your interrogation of neuroscience and scientism reveals something fascinating, which is that scientific knowledge production seems to rely heavily on race while race remains absent from any formal vernacular of science. In the past, you have described this as an “absent presence” of race. Could you elaborate on this phenomenon and specify how you saw this play out in your ethnographic research and interviews on the neuroscience of violence?

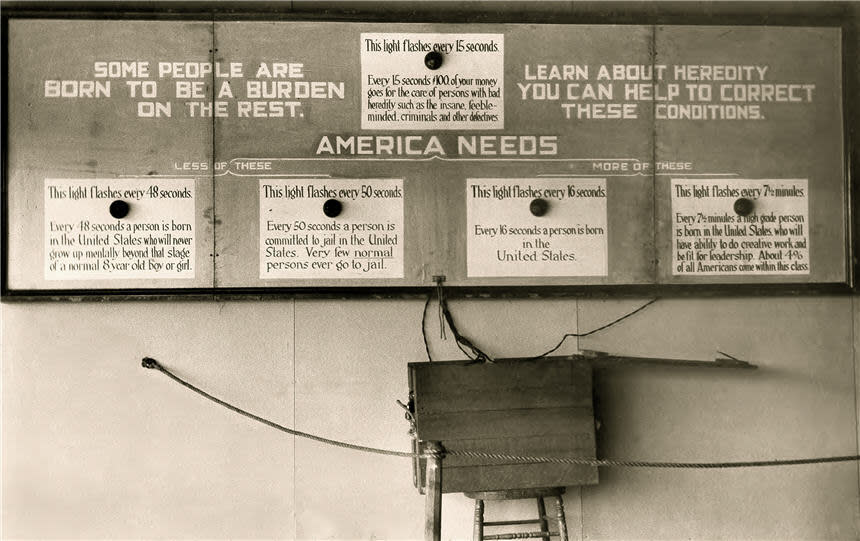

Oliver Rollins: The term “absent presence” has a longer history to it. I came across the term while reading a piece by Amade M’charek, Katharina Schramm, and David Skinner called “Technologies of Belonging” in the Journal of Science, Technology, and Human Values. The piece was published in 2014, but it stuck with me as I was writing my book. Absent presence means that there is a phenomenon—an object, person, whatever that may be—whose presence is felt even without that person, thing, or phenomenon being there. In their piece, they talked about the absent presence of race in Europe. For me, it raised a question in my work about how scientists who study antisocial behavior, violence, and criminality are at once trying to move away from race while simultaneously being haunted by the history of race, scientific racism, sexism, eugenics, and so on.

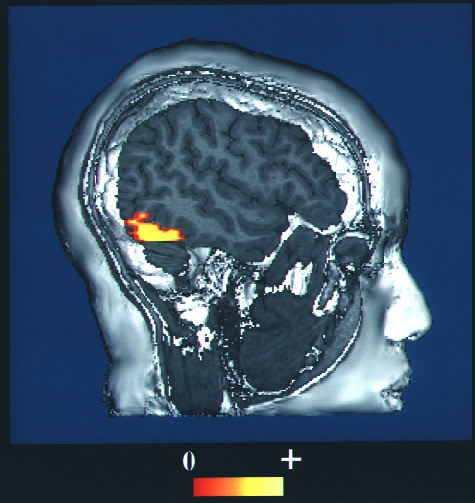

I began with a large-scale review of neuroscience papers in which I focused on neuroimaging as a technology, particularly as it is employed to discern crime or antisocial behavior. How would they deal with this question of race? If you go through that literature, you’ll see that race—as in the term “race”—is largely absent. When it is present, it’s really confined to the demographics of study populations—for example, “we match the study population to the control population along the lines of race,” or something like that. Very little engagement with race beyond that, and no talk of racism at all.

At the same time, in the early nineties, we’re having these conversations about race and genetics, particularly with regard to behavioral genetics, race, and crime. Often, these are similar people—and sometimes the very same people—who were working within the field of genetics and doing this work in neuroscience.1 So what really caught me was, where is the talk about race and the neuroscience of crime? My interviews with neuroscientists gave me the perception that there’s something about race that they are running away from. A good example of this is when one neuroscientist said to me, “I teach about race in classrooms, but I don’t talk about race with my peers.” That made me think: Okay, well, you’re teaching it but not comfortable talking with peers about it—so it is structuring the shape of this research program without being a visibly central part of the research.

I also asked them how they deal with racism. Neuroscience research on crime is a kind of predictive science. I call it a risk of risk, because what they are trying to predict is the chance that someone will exhibit characteristics of psychopathy or antisocial behavior—which they argue places that person at higher risk of participating in criminal activity. With this in mind, racism seems to be a huge factor in understanding behavior—not simply that of people who may be violent, but the behavior of society toward those people that influences them to act in these ways. When asked about racism, these researchers told me that racism is too complex to fit in a model. This raises a secondary question: If we cannot put racism within this model, then who is the model for? How can we “accurately” predict whether or not a young Black kid is gonna grow up to be violent if racism is not a factor in that model? I really question if such models can deal with systemic inequality, such as poverty—larger structural forces within our society that we can often feel and that we know impact our experiences with violence, though we can’t necessarily see that absent presence. The science, however, does have legal implications. If the point of this science is to make “better” predictions, let’s say, of who can or will become a criminal, then it is a direct contribution to a highly racialized criminal justice system. Also, there is an ethical question here. Since they try to predict as early as possible, let’s say a five-year-old or seven-year-old kid is found to have a high risk of demonstrating psychopathic or criminal behavior. What, then, exactly are you asking the society to do with that child? That’s not being answered either.

So there’s both the legal question: Are we actually making the legal system more efficient toward injustice by scientistically overlooking these structural factors? And the ethical question: What are you asking society to do with this notion of risk?

If we cannot put racism within this model, then who is the model for?

Sucheta: Do the neuroscientists who are invested in this research see this as an ethical challenge?

Oliver: Yes and no. I think it’s important to know that this science, just like any other science, is not monolithic. And that’s probably one of the most fascinating things for someone engaged in science and technology studies—scientists never really fully agree on what these things are. When you really dig in, you see that there’s no consensus. Some people are really concerned with the implications of this science. For example, the person who told me racism is too complex also said, “I know it’s important, but I just don’t know what to do with it. We just don’t have the technology or the capability to really understand how to place that within this kind of model.” Then there are those who have faith in a colorblind model.

Sucheta: I am curious about the incentive structures that are driving these neuroscientists who are moderately concerned but also have faith in colorblind ideologies. Considering that this research has the potential to inform legal systems already hungry for racially deterministic explanations of violence, how do they justify their work? Are they telling you about their individual research aspirations? Are they talking about specific funders and their interests and goals? As a researcher and faculty member at a university, I know that science is rarely purely based on passion or intellectual interests. There’s just so much else that restricts and enables research. Could you tell us about those elements of the neuroimaging field?

Oliver: As a sociologist, I was a little less focused—not less interested but less focused—on personal reasons, or why these researchers study what they study. But of course, this comes out in the interviews. On the one hand, yes—obviously, most of us are incentivized to go after grants that will allow us to continue our research; because you need tenure. You need funding. You need publications. You need all of these things.

There’s something important about the structure of science and how it’s being funded right now. Research on the neuroscience of violence follows the same practices and tools as any other “legit” neuroimaging project. Moreover, the funding sources are the same. Those studying violent behavior might also contribute to the neuroscience of emotions. They may want to know what it means for someone who supposedly is psychopathic to “lack” certain emotions. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) is not necessarily funding research into crime or race with the aim of concluding whether Black people are more prone to being violent than others. That’s not what’s happening. Funders are increasingly prioritizing funding for sciences that utilize genetic, neuroscientific, and now AI-based logics as the best tools to understand and potentially solve our social problems. This, in turn, invites and incentivizes the research that continues—despite the potential ethical or social harms—to toe the line of racial science.

Sucheta: I think about that a lot in terms of my work, too; lately it seems like anything AI is the thing to fund. There are so many different questions one could ask around AI, but when trying to write up a grant proposal that identifies a societal problem and proposes a solution involving AI, it will most likely end up being reductive and antiblack; after all, a solution that tries to solve racism in three years is always going to be a racist solution. Because of their apparent solutions-based focus, the economic structures of academic research in science and computing often create fake opportunities and restrict the research that could help resolve a meaningful research question. For neuroscience research of the kind that ultimately wants to solve crime, though, it seems there is already a very specific answer: it’s always punitive. Would a federal funding agency ever be happy with a solution to crime that is complex and doesn’t end in a simple solution of punishment?

Funders are increasingly prioritizing funding for sciences that utilize genetic, neuroscientific, and now AI-based logics as the best tools to understand and potentially solve our social problems.

Oliver: This is why I ask: What is the point of this science besides making the system we already have more efficient? There’s a normative valence to neuroscience that we must call out and address. My framing for this comes from the work of Troy Duster, whose writings on genetics and crime raise the question of what he calls the “theoretical warrant” for this line of research. Following Duster, I’m noting that biocriminology of the past and neurocriminology of today have yet to justify and precisely outline why this particular set of socially constructed (e.g., violent, criminal, or antisocial) behaviors require biological explanation or attention.2 In other words, given the vast spectrum of social behaviors, why does the research program, as well as public interest, invest so much scientific capital in the study of violence and continue to try and find biological roots of violence, even though each venture has been a failure?

Genetics, for Duster, and neurobiology, for me, have both failed to answer the question of why we need—and whether we should trust—technoscientific approaches to discerning criminals from noncriminals. That is an epistemological, if not ontological, assumption that we have throughout society. But the reality is that we don’t know what it means to be “normal,” let alone what it really means to be criminal. Criminals are just people we have “caught” or put through the justice system. There is no identity, and these are not fixed categories, so what in the world could biology tell us about these ideas? If we know that what it means to be a criminal in one space could be very different from what it means another, that the same notion of crime could be treated differently in different spaces, then why are we trying to use this “objective measure of biology” to then predict these things?

So to think about scientific racism today, we have to understand that the funding is not so much for new science per se as much as it is for confirming social concerns of our time. Why is it that we want to know the biology of the criminal? Why do we believe that this person is so different—that this person would have such a distinct biological makeup than anyone else? And, you know, we’ve focused a lot on genetics, on neuro, and now on AI, specifically with predictive policing models. All of this comes back to the social concerns of the age and not the newness of the science. It’s an old question that we keep using new tools to come back to.

I’m noting that biocriminology of the past and neurocriminology of today have yet to justify and precisely outline why this particular set of socially constructed (e.g., violent, criminal, or antisocial) behaviors require biological explanation or attention.

Sucheta: That is why I found your argument in Conviction about scientism, as it’s employed by the state or the market, so powerful. If you’re not budging on your question, no matter how much scientific research tells you otherwise, then your investment is in the question itself, and you have the power and the money to shape what conclusions can be drawn in response. When you’re talking to neuroscientists, do they mention anything about chasing grants or funding restrictions?

Oliver: There are several ways I see researchers thinking about funding. We know that the budgets of the NIH or the National Science Foundation (NSF) can shrink or expand depending on our political environments, right? So when people are thinking about their careers, they’re thinking, Okay, how do I ensure that I have the resources I need to do the work that I need to get tenure? But I think that, given the focus on brains and the NIH’s Brain Initiative money, neuroscience researchers are not necessarily that worried about getting their work funded. I think there will be consistent ways for that research to be funded. The Brain Initiative, by the way, was Obama’s big scientific project. It’s a huge project that was really set up to think about how we advance neurotechnologies.

Sucheta: As you know already, Logic(s) has been trying to curate articles on neuroscience and on medicine and the body more broadly. As we were speaking to potential contributors working in the fields of cognitive science and neuroscience, it seemed like a lot of them have ties to military funding for their research. I keep thinking about this—and my familiarity, again, is with AI research. I’ve thought about Phil Agre, who is an AI researcher at MIT and writes about the militarization of AI innovation and research. He grapples with this moment in history when AI research was suddenly enabled by unrestricted funding from the military, observing that for AI to undo its military foundation would be a near-impossible task. In Logic(s) 21, “Medicine and the Body,” cognitive scientist Chris Dancy similarly reflected on the militarization of his field. Do you have any thoughts, findings, or general insights on how you have seen military motivations and military funding shape the neurobiology of violence?

Oliver: Yes, I do think there are absolutely military ties to what neuroscience is doing. I mean, in the US, vast amounts of funding are allocated for the military at the expense of education. That funding seems both to be less scrutinized and to lack the same degree of public oversight.

The kinds of questions that military interests in neuroscience have come to shape include, for example, that of suicide prediction. Or the question of whether or not neuroscience can help us identify particular kinds of neurobiological signatures that would help predict, at an early stage, who may be terroristic, who may be vulnerable to violent extremism. Also, honestly, I don’t necessarily separate policing from the military in the US. A good example of how their interests converge is in the research question of whether we can use neuroscience to predict who will return to prison. And of course, again, we already have sociological measures that suggest who will come back to prison. I mean, I often jokingly say that if we just know the zip code of where people are returning home to, we probably have a good understanding of whether or not they will be reincarcerated—and that has nothing to do with them individually. Anyway, this raises the question: Why is it that we want to be able to predict these things in the first place? Instead of investing in predictive technologies, why not change the social structure?

Sucheta: Interestingly, the question of how to predict suicides may have been a military invention, but it has since been asked in the context of mental health and social computing research—for instance, in the use of Reddit confessions or social media posts to predict suicide risks. I also struggle to locate what such prediction, at its core, has to offer that is useful for the public, beyond, for instance, to medical insurance companies. Maybe there is an element of prediction that some people more than others expect or desire as a way to grasp the uncertainties of everyday life—but not all such desires need to be developed and designed for. To me, channeling that predictive impulse in the service of institutional structures such as the military, or even the medical insurance companies, feels very sinister.

Oliver: Yeah. It’s the same question I asked around, like, “What are you asking society to do with this kid if we find out that they are at risk of exhibiting antisocial behavior?”

As you were saying, though, I think there are also implications of this kind of research for carefully cultivating market interest around surveillance and monitoring. Let’s say someone is declared at risk for violence, which would then somehow warrant surveillance and monitoring of this person, of this group. You know, there are folks who already do what they call neuroforecasting and neuromarketing. So there’s already a business interest there.

Sucheta: Yeah, and this is precisely why I remain invested in interrogating the logics of capital that shape the US academy. I mean, in this example that we are discussing—suicide prevention—what is the interest of national security in suicide prediction for soldiers? Why are you invested in saving that life—is it for the sake of their loved ones or for the soldier’s unfulfilled dreams, or is it that you would rather that life be sacrificed in the interest of national security? For me, this is a disturbing yet appropriate example of how scientific research ends up performing interests that stem from nationalistic or capitalistic ambitions.

Considering, as we have established from various angles, that academic research and specifically neuroscience research are often bound by state, market, and military interests, how do you perceive the ethical and political responsibilities of neuroscientists whose research ultimately contributes to racialized notions of violence?

Oliver: They absolutely do have an ethical and political responsibility, and in fact I don’t think that you could separate those things out. In fact, in a piece I am currently working on, I interrogate what an anti-racist neuroscience research looks like. There, I am saying that we need more than neuroethics. We actually need a politic. I want these researchers to be political in the sense of taking a stance on what their work actually means. And I don’t think this applies only to neuroscientists who are working with humans. For the neuroscientists who are, perhaps, studying neurons in slugs, what would it mean for them to be anti-racist?

I think this is where we come to confront your provocation on the political economy of scientific research. Thinking with Robin D. G. Kelley here, we need to imagine what we want that future of science to look like. Also, more than simply diversifying your lab, you could raise social and political questions about the research infrastructure of your labs. Who are the vendors that you buy from? Where are the materials for this microscope, for this fMRI coming from? Who’s putting it together? What are their politics? What places, transnationally speaking, are affected by your doing your research in this way? And how can you use your social and scientific capital to change that?

I think this requires a different kind of imagination. I’m still thinking through what other ways that potentially looks like, but I don’t think it simply means you need more Black people in your lab. Nor does everyone who’s now working on the project need to start talking about race; half of them don’t know how to talk about race in the first place.

We need more than neuroethics. We actually need a politic.

1. In Conviction, Rollins notes: “Genes that have been linked to violent behaviors are said to moderate the brain’s ability to regulate conduct. More specifically, they are ‘neurogenetic’ biomarkers thought to raise an individual’s risk for personality disorders, and hence increase the propensity for violent or antisocial behavior. It is more appropriate, therefore, to consider neuroscientific and genetic approaches to violence as sociotechnical practices—instead of distinct disciplinary groupings—united under a neurobiological thought-style of violence.”

2. Erik Parens, Audrey R. Chapman, and Nancy Press, eds., Behavioral Genetics and the Link between Crime, Violence, and Race (Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 2006), 150–75.