This conversation between UC Berkeley professor Eric A. Stanley and abolitionist organizer Ralowe T. Ampu maps cycles of displacement in San Francisco. Ampu traces the ongoing removal of Black life from her arrival in 1996—a year that also marks the election of the city’s first Black mayor, Willie Brown, and its first tech boom—to the present. Foregrounding the ways Black politicians spearheaded the dispossession of San Francisco’s Black communities, and drawing on a storied history of organizing against these violent modes of urban planning, Ampu provides unique insight into the everyday implications of computation as a municipal project.

Eric A. Stanley: Perhaps this is a strange place to start our conversation, but I know you have feelings about the film The Last Black Man in San Francisco (2019). You’ve offered critiques, which we could talk about, but one of the scenes that exists beyond the film is the one in which Jimmie is riding the bus in San Francisco. There are some techie stand-ins—which is a bit confusing because they almost never ride the bus in real life—who are complaining about San Francisco, and Jimmie responds, “You don’t get to hate it unless you love it.” I think his statement approximates the affective landscape many of us exist in, here. By way of an introduction, can you talk about what brought you to this city, and what keeps you here?

Ralowe T. Ampu: It’s interesting because it took them a very long time to make that movie, and its release marks a particular moment when previous generations of anti-eviction organizing in San Francisco were fading. So many people had been evicted—including Iris Canada, a 100-year-old Black woman who lost her eviction case and then died. There was defeat after defeat, and a massive ceding of ground in the anti-displacement fight. In the end, that scene arrived at a certain moment in history; and instead of chronicling that struggle, the movie ends up being a monument to our collective loss.

My main critique of the film is that I wanted the Black characters to be queer, as their intimacy was going in that direction, but there was an invisible wall between those worlds. The filmmakers don’t show queer life in any sort of significant way.

I guess another way to answer the questions that you’re asking about how I came to San Francisco, and about loving and hating it—I mean, I came here to be part of queer and trans life. I moved here from Southern California, which was kind of a blank, desolate suburban environment, and I just needed to get out. I moved here in ’96. It was the same year Willie Brown took office, and it was the height of the first tech boom, which created the massive displacement of Latinx and Black people out of the City. Gentrification was not new, and this is all stolen Ohlone land, but to see entire blocks get evicted and watch white and Asian techies take their homes was a lot. I was living in a single-room-occupancy hotel in North Beach then; I live in a different SRO in the Mission now.

Eric: It’s interesting that you talked about The Last Black Man in San Francisco as being almost like a monument to the failures of anti-gentrification work.

Ralowe: Oh yes, I feel like it is.

Eric: The long history of Black removal from San Francisco a well-known historical fact; James Baldwin documented it in the film Take This Hammer in 1964. However, the fact that it’s an ongoing process—not something that ended in the early 1970s—gets a lot less attention. You have said that the war against Black life in San Francisco is one of the defining features of the City, and as an alleged remedy to this condition, Willie Brown was elected as the City’s first Black mayor in 1996. Yet he is also credited as the politician that rolled out the red carpet for tech in particular and real estate speculation in general. Can you talk about Willie Brown and his enduring legacy—which seems to still be dictating life in the City?

Ralowe: Like many neoliberal Black politicians of his generation, Willie Brown is characterized as a former civil rights leader. Through his decades in California politics, he amassed an amazing amount of influence, connections, and experience. He didn’t personally engineer Silicon Valley, but he was in a position to capitalize on the desire of early tech people to “disrupt” San Francisco—as in, take it over.

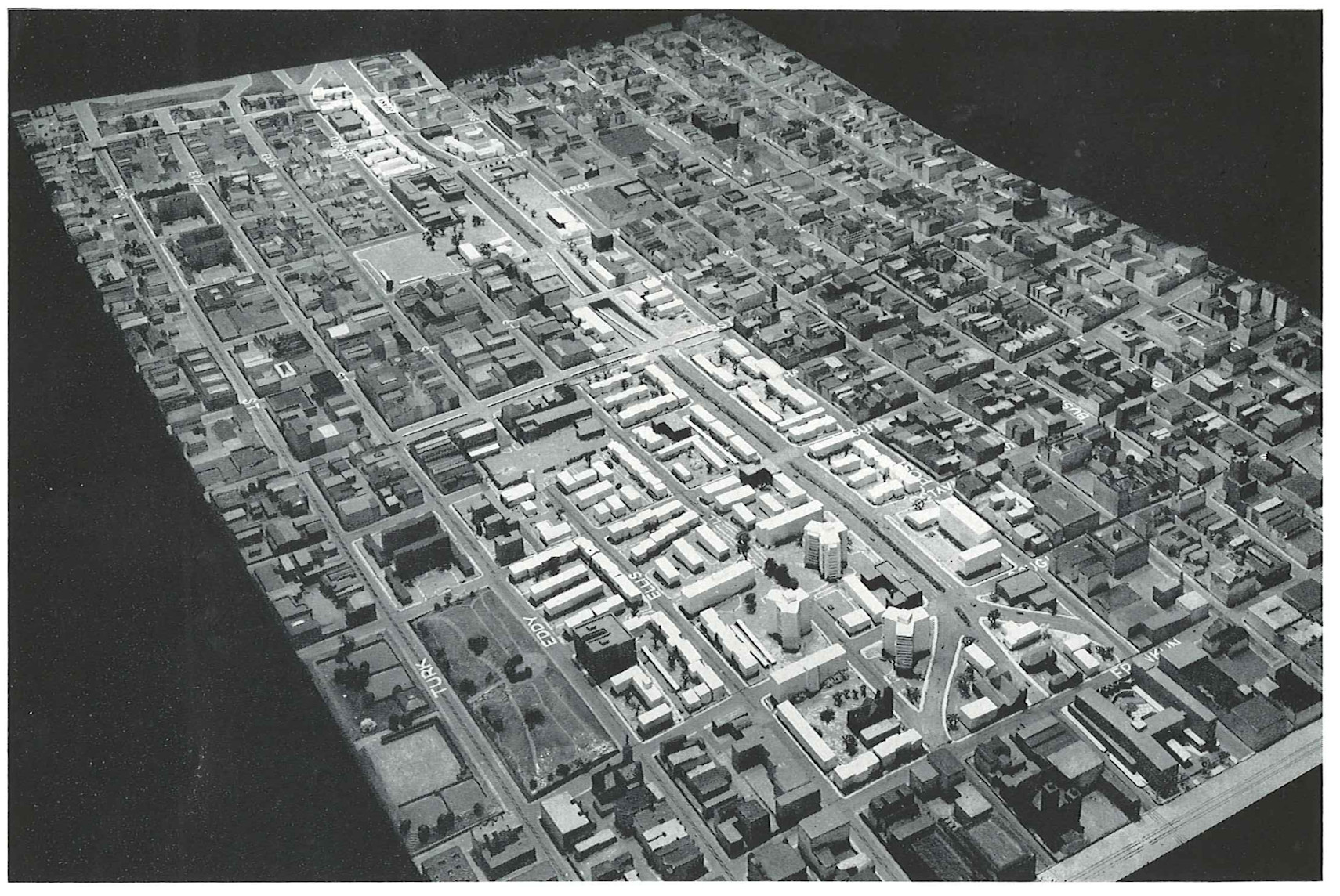

While he was central to establishing many of the policies that made tech companies richer—tax breaks and that kind of stuff—all the cultural changes that he supported are what really accelerated gentrification: things like the conversion in the 1990s of production, distribution, and repair warehouses, where working-class people worked, into luxury “live/work” lofts in South of Market, or SoMa, for newly minted millionaires to park their Hummers, the Teslas of the time.1 These small zoning changes were not about specific buildings, but Brown’s strategy ushered in the second wave of urban removal. The little space that Black San Francisco had held onto from the 1960s, he was dedicated to stealing and handing over to his tech developer supporters. Like, just look at what happened to the Fillmore under his watch.

Eric: A lot of the “live/work” lofts were advertised as artists’ spaces but then were sold to techies because most of the artists were forced out. Techies were into the idea of urban living but rejected the hassle of living in the City. They moved here en masse, but not because of the culture; then they wanted to remake the City in their own image and not become part of it. How else did Brown influence both Black life in the City and the proliferation of tech?

Ralowe: Brown was always down for whatever would get him the most money and power—his ideology is just like a fire sale. He was cool with getting rid of all of it in favor of the dollar. We sort of live in the wake of that.

Eric: Following that, I also think it’s interesting that tech in the 1990s focused on SoMa, and it’s important to know the relationship between SoMa and downtown San Francisco. There have been lots of para-successful gentrification projects all throughout SoMa. Yet there are still a lot of SROs there, and it was a historic center for queer leather culture in the 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s—much less so now. So it was always kind of lying in wait for developers.

Geographically, SoMa ends at Mid-Market to its north, which remains one of San Francisco’s last Black public spaces, and further north is the Tenderloin. Market Street is also one of the primary arteries of San Francisco, so it functions as a contact zone where lots of kinds of people brush up against each other—and that becomes a problem for capital. If you’re staying at a fancy hotel downtown, for example, you might accidentally end up in Mid-Market.

It could be said that the history of Market Street is the history of its attempted destruction, called redevelopment. More recently, we had the “Twitter tax breaks,” where the mayor and board of supervisors voted to give bags of cash to Twitter to stay in Mid-Market as a “civilizing” project—tech colonialism in action.

Ralowe: Yeah, the Twitter tax break, which is not just for Twitter—a number of other tech companies also got the breaks. I think the correct way to interpret it, because of where Twitter is located, is as an assault on Black culture and a continuation of Frank Jordan and Willie Brown’s war on drugs—which the current mayor, London Breed, is now expanding. The Redevelopment Agency emptied out Hayes Valley to make it habitable for white window shoppers, and tons of rent-controlled buildings have been torn down. The fullness of Black life is worth less to capital than empty condos.

I lived in a residence hotel on Market in ’97 or ’98. It’s wild going back and looking at it now and seeing how much of it has changed. The place that was an adult theater right next door is a corporate playhouse. Especially now, after all the office closures and the tech exodus, they are really trying to bring empty corporate culture to Civic Center, which is pretty funny. They spend tons of money on these “Civic Joy” events, and then there are one or two people watching a drag queen perform while cops hassle houseless trans women a few feet away. Not to reduce Black people to culture, but if you get rid of the Black people, you’re getting rid of a lot of culture. You’re getting rid of a lot of things that are not favorable to weird, sheltered techies from suburbia who don’t know what a city is like.

The fullness of Black life is worth less to capital than empty condos.

It is interesting because you see so many neoliberal principles of the primacy of the market in daily contact zones with these sheltered techies who only care about the online world, or the market, or whatever—and you see the absence and the emptying out of sociality with the emptying out of Black life. That typifies the neoliberal city—not just here in San Francisco but worldwide. When you want to hyper-financialize things, you’re putting the primacy of the market over the sorts of relationships that we build on the street, and tech is constantly trying to replicate that online.

But thinking about Black Twitter, I mean, we used to joke that Twitter would put a Black Lives Matter mural in their headquarters—and then they did it.2 Nothing captures the City like that image and the generations of loss that allowed it to get painted there. What about the terror that Twitter, as a place on Market Street, inflicts on Black people in San Francisco? We don’t count.

I’m really coming down hard on Willie Brown, but not as hard as he does on us. I have a lot of feelings about him. Because I was thinking about the complete erosion of a kind of political consciousness, and of Black political life, around Black people and the relationship that we have to capitalism. The ethics of neoliberalism have traveled so far through Black culture that we don’t even interrogate the legacy of being a commodity. It seems like we would all, more than any other people, be particularly horrified about commodification, but people seem ready for it.

The ethics of neoliberalism have traveled so far through Black culture that we don’t even interrogate the legacy of being a commodity.

Eric: Something that you’ve been vigilant about is that tech’s problem is not only, or even primarily, at the level of employee diversity, or that tech produces racist algorithms. All those things are true. But if the analysis stops there, then it works as a form of counterinsurgency, as you open a door for a murderous company to hire a Black CEO and keep on. What, then, is an abolitionist’s understanding of tech, knowing that perhaps there are some things that tech makes that are useful? We can think about what that understanding looks like, what constitutes tech, and the impossibility of reforming a fundamentally—which is to say foundationally—anti-Black, anti-Indigenous, ecocidal project.

Ralowe: I feel like I’m a Willie Brown scholar, but I really think that Willie Brown’s reign over San Francisco is instructive of the technocrat’s cultural ascendance; because Brown is this skillful person who uses policy in these transformative ways. He’s deep inside the machine. He’s in the system; he is the system. Similarly, something that I’ve commented frequently upon is the election of so many Black mayors in other major metropolitan areas throughout the United States, and how their role as technocrats is to devise policy solutions that create more terror for Black people. Look at Cop City.

What we are seeing now is the failure of the idea that tech and its disciples can solve every issue through these technocratic fixes. What’s dangerous is that now, many of our anti-colonial, antiauthoritarian struggles have also begun to internalize this idea. As one example, much of what queer and trans communities learned when AIDS unfolded in the ’80s has been lost because of this fantasy that technology will deliver freedom and connection for us all.3 We also saw this with the app-ification of COVID. We need free housing, food, and healthcare, while the technocratic state just makes another public–private partnership with some tech overlord to build an app, which directs people to resources that don’t actually exist in the real world.

Eric: Something you’ve elucidated is that even if every person that worked at Twitter were Black, Twitter would still demand more cops—more Black cops—on Market Street.

Ralowe: Yes. I mean, that’s what Black mayors show us—it’s the same philosophy. We’re still dealing with the white supremacist legacy of the United States. Why would we expect that the experience of being Black leads everyone toward liberation and not to fascism?

Eric: So, like you’ve already said, you have lived in an SRO hotel in Mission for many decades now. That’s a long time. The paradox of the Mission is that because it was seen as a kind of cultural enclave, it drew techies that wanted the culture but not the people that made the culture. This has made the Mission into a long-term battleground, perhaps par excellence, against displacement. How have Sixteenth Street and Mission changed from the mid-’90s to our contemporary moment?

Ralowe: Oh, yes. I mean, where we’re post–Willie Brown, we’re post–Gavin Newsom, we’re post–Ed Lee’s brief moment (before he checked out), and now deep into London Breed and her nonsense. The San Francisco that we live in now, the complete erosion of public space in favor of tech—they’re just so deeply intertwined. You can see with the complete obliteration of benches, of awnings, of little architectural features that are nice and that will help you withstand the elements—they’ve all been completely stripped down and removed and destroyed, particularly where I live on Sixteenth and Mission.

It’s kind of funny. On the bus here today, I was looking out the window, and I noticed it’s a regular ritual now that they’ll have a police cruiser sitting in the Sixteenth Street BART [Bay Area Rapid Transit] plaza. This is in response to people like Garry Tan, who is the new face of SF fascism, and his ranting about how people are selling stolen stuff and drugs on the street.

People who live in my neighborhood are overcome by economic desperation. But aside from that, people just want to be outside minding their own business. For those who are convinced that the world only wants door-to-door Uber service or DoorDash delivery, the idea that some people do need to go outside for a variety of reasons, economic desperation not the least, is unthinkable. Lots of people in my building are disabled and use mobility devices. They can’t move in their tiny rooms, so they hang out on the street.

London Breed has ramped up her war on people selling stuff in the Plaza. She argues that it’s dangerous and illegal—and yet she loves the “move fast and break things” ethos of the tech industry. So what kinds of economics are valid? If people are trying to sell stuff to make rent or need drugs or whatever, they’ve got to go, but Google can build a driverless car that parks on your neck, and it’s cool?

So, back to that point about how gentrifiers want the culture and not the people, the City has recently been organizing these sanctioned and sanitized night markets. And yet, it’s kind of funny because the Plaza market does still happen—I probably shouldn’t say this. Once the police cruiser leaves, they’re back to it.

In San Francisco, and maybe everywhere, it feels like we keep mourning the loss of all these spaces and all these different places where we can conspire and build. An undercommons has been completely stripped of us, and instead there’s a weird undercommons being made by billionaires in fake night markets and luxury condos with murals on the facades.4 It’s kind of ironic, because the original idea of BART plazas was that they would be town squares, public gathering spaces for the neighborhood, and now you have a square at war with the neighborhood and the idea of a public.

Eric: Speaking of being at war with the idea of a public, you and some other Black queer and trans anarchists staged a protest against London Breed when she was running for mayor in 2018. Can you talk a little bit about the response, and why you think pushing against all mayors—but for you, Black mayors in particular—is vital right now for Black radical organizing?

Ralowe: So, that went down before the George Floyd uprisings of 2020. Hopefully now, people are a little more on top of it, particularly as we saw these Black mayors in different US cities going after abolitionists and Palestinian solidarity organizers.

Basically, what happened is that we got run out of the event by a crowd of white gay nonprofiteers and Black staff. It was at the Castro Theatre, which adds another level. They were all furious that a group of Black trans and queer people would dare question their antiblack Black girl boss.

But anyone who knew anything about London Breed could see the future if she were to become mayor—and it’s all happened, and worse. The thing that I always tell people about her is that she encouraged Black people to turn in their family members to the police if they thought that they were involved in a crime. Just think about that against the context of all the Black Panther organizing in the Western Addition (including the Fillmore), where Breed grew up. A lot of what the Redevelopment Agency was trying to do was get rid of all that shit. She is finishing the job of redevelopment by getting rid of any other ways of building togetherness. She’s working to destroy the Black undercommons.

Eric: I’m not going to ask you about hope or anything like that, but what maneuvers should the Black trans undercommons be taking collectively right now?

Ralowe: I used to really want there to be a kind of—I don’t want to say polymorphous, but a kind of Black queer transsexual thing that happens. I’m always unclear about what that could look like, I guess, because I get too in my head about it. But again, there’s an interesting documentary about Freaknik, so I don’t know if I would say—

Eric: A trans Freaknik?

Ralowe: Yes, Freaknik is, notoriously, not queer or trans. But I don’t know. I mean, I guess that’s another question that I’m still thinking through, in the wake of organizing around Michael Johnson’s freedom5—whether those are even political possibilities for Black queer and trans people. It just feels like the institutional narrative of what intimacy looks like and the politics of intimacy is so shut down. How can we render it in language when we have been so intensely overdetermined by these incredibly savvy and sophisticated management apparatuses? That’s why I keep organizing and think everyone else should too.

I could say something like that right now, then I could immediately regret saying it.

I mean, living in San Francisco, at one point there were 3 percent of us. Now there are, allegedly, 6 or 7 percent, which I don’t believe; and if they are, they’re probably all DEI [diversity, equity, and inclusion] people. We don’t need to talk about DEI. I guess we have soundly said that DEI is a sham, a scam, and no one should fall for it. I don’t know, trying to bring blockchain to the hood. What’s next? I guess it would be bringing AI to the hood, which could have a whole lot of meanings too, all of them bad.

What’s next? I guess it would be bringing AI to the hood, which could have a whole lot of meanings too, all of them bad.

So yes, I don’t know. Thinking of AI as another version of the laborer without personhood, the ultimate digital laborer without personhood, and the idea of trying to bring that to Black people? I don’t know if Black people feel like they want to claim that legacy—hopefully not. I guess that’s all the hope I have.

1. Francisco Diaz Cacique, “Race, Space, and Contestation: Gentrification in San Francisco’s Latina/o Mission District, 1998–2002” (PhD diss., University of California, Berkeley, 2013), 4–5.

2. Farida Vis et al., “When Twitter Got #Woke: Black Lives Matter, DeRay McKesson, Twitter, and the Appropriation of the Aesthetics of Protest,” in The Aesthetics of Visual Protest: Visual Culture and Communication, ed. Aidan McGarry et al. (Amersterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2019), 247–66.

3. See, for instance, United in Anger: A History of Act Up, documentary film, Jim Hubbard, dir., 2012.

4. The term “undercommons” is credited to Fred Moten and Stefano Harney. 5. For more on the campaign to free Michael Johnson, who served five years in prison following a conviction under Missouri laws that criminalize the transmission of HIV, see David Artavia, “Former College Wrestler Convicted of HIV ‘Exposure’ Freed From Jail,” Advocate, July 9, 2019; and “Free Michael Johnson,” Gay Shame (blog).