In 2019, Berlin celebrated Equal Pay Day by offering women discounts on public transit. It provided these discounts automatically, by analyzing the faces of people purchasing tickets. On the face of it, as it were, this approach might appear innocuous (or even beneficial — a small offset to gendered pay disparities!). But in actual fact, the technology in question is incredibly dangerous.

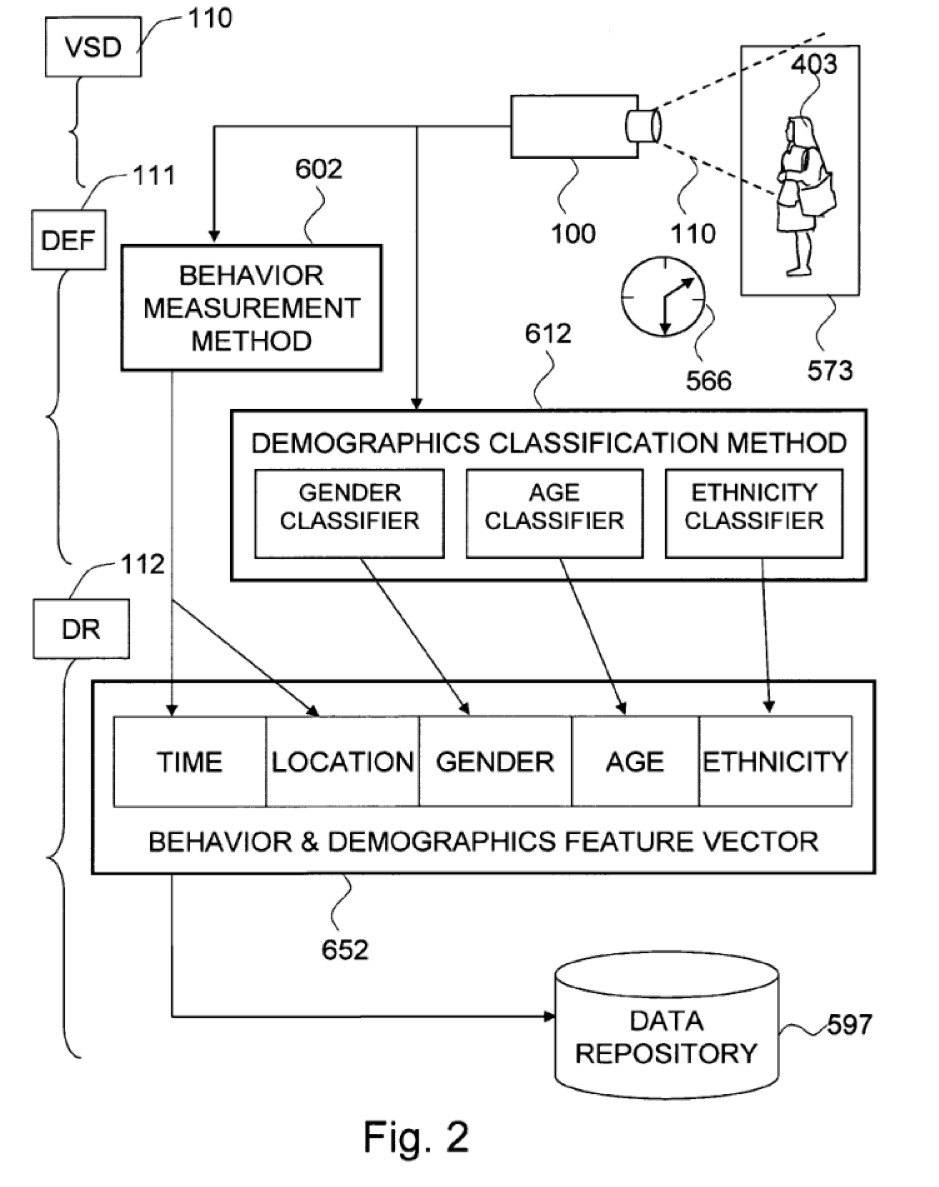

Automated Gender Recognition (AGR) isn’t something most people have heard of, but it’s remarkably common. A subsidiary technology to facial recognition, AGR attempts to infer the gender of the subject of a photo or video through machine learning. It’s integrated into the facial recognition services sold by big tech companies like Amazon and IBM, and has been used for academic research, access control to gendered facilities, and targeted advertising. It’s difficult to know all of the places where it’s currently deployed, but it’s a common feature of general facial recognition systems: anywhere you see facial recognition, AGR might well be present.

The growing pervasiveness of AGR is alarming because it has the potential to cause tremendous harm. When you integrate the assumptions embedded in this technology into our everyday infrastructure, you empower a system that has a very specific — and very exclusive — conception of what “gender” is. And this conception is profoundly damaging to trans and gender non-conforming people. AGR doesn’t merely “measure” gender. It reshapes, disastrously, what gender means.

The Algorithmic Bathroom Bill

So what precisely is AGR, and where does it come from? The technology originated in academic research in the late 1980s (specifically in psychology — but that’s another story) and started off with a particularly dystopian vision of the future it was creating. One early paper, after noting AGR’s usefulness for classifying monkey faces, proposed that the same approach “could, at last, scientifically test the tenets of anthroposcopy (physiognomy), according to which personality traits can be divined from features of the face and head.” Malpractice and harm have never been far from these systems.

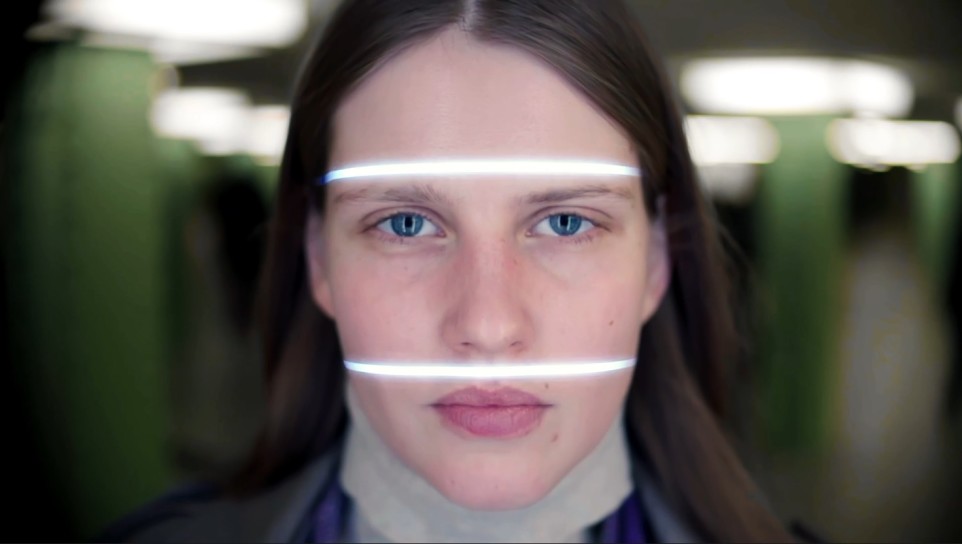

When you run into a system that uses AGR, it takes a photograph (or video) of you, and then looks at your bone structure, skin texture, and facial shape. It looks at where (and how prominent) your cheekbones are, or your jawline, or your eyebrows. It doesn’t need to notify you to do this: it’s a camera. You may not even be aware of it. But, as it works out the precise points of similarity and difference between the features of your face and those of a template, it classifies your face as “male” or “female.” This label is then fed to a system that logs your gender, tracks it, and uses it to inform the ads that an interactive billboard shows you or whether you can enter a particular gendered space (like a bathroom or a changing room).

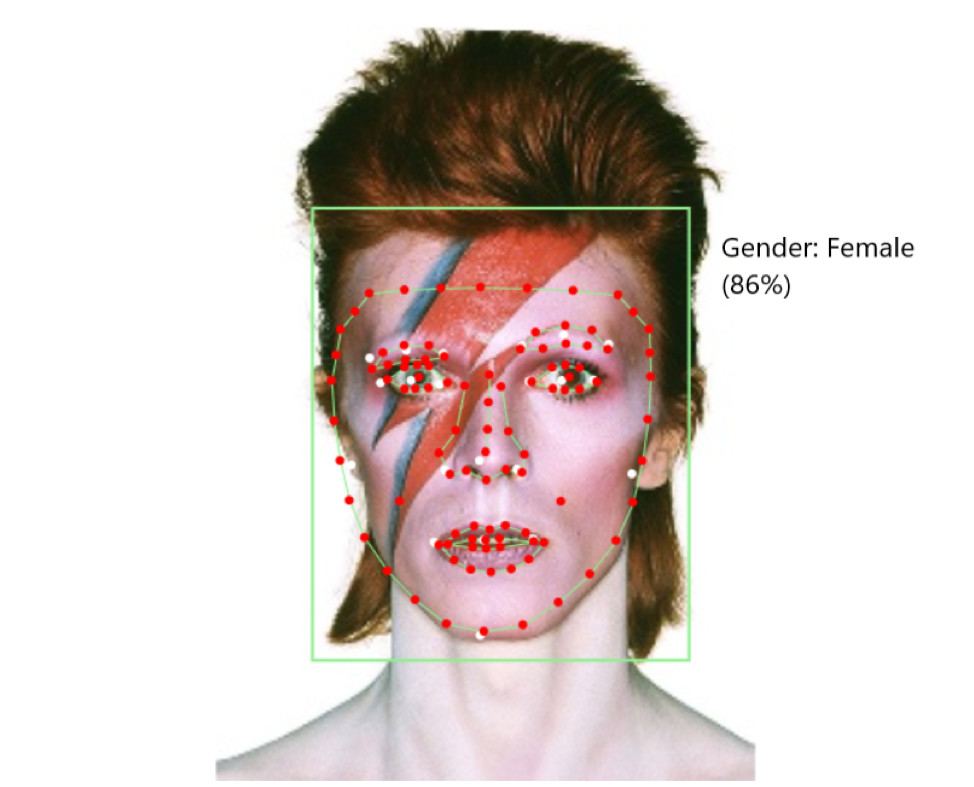

There’s only one small problem: inferring gender from facial features is complete bullshit.

You can’t actually tell someone’s gender from their physical appearance. If you try, you’ll just end up hurting trans and gender non-conforming people when we invariably don’t stack up to your normative idea of what gender “looks like.” Researchers such as myself and Morgan Scheuerman have critiqued the technology for precisely this reason, and Morgan’s interviews with trans people about AGR reveal an entirely justified sense of foreboding about it. Whether you’re using cheekbone structure or forehead shape, taking a physiological view of gender is going to produce unfair outcomes for trans people — particularly when (as is the case with every system I’ve encountered) your models only produce binary labels of “male” and “female.”

The consequences are pretty obvious, given the deployment contexts. If you have a system that is biased against trans people and you integrate it into bathrooms and changing rooms, you’ve produced an algorithmic bathroom bill. If you have a situation that simply cannot include non-binary people, and you integrate it into bathrooms and changing rooms, you’ve produced an algorithmic bathroom bill.

A True Transsexual

So AGR clearly fails to measure gender. But why do I say that it reshapes gender?

Because all technology that implicates gender, alters it; more generally, all technology that measures a thing alters it simply by measuring it. And while we can’t know all of the ramifications of a relatively new development like AGR yet, there are a ton of places where we can see the kind of thing I’m talking about. A prominent example can be found in the work of Harry Benjamin, an endocrinologist who was one of the pioneers of trans medicine.

Working in the 1950s, Benjamin was one of the first doctors to take trans people even marginally seriously, and at a vital time — the moment when, through public awareness of people like Christine Jorgensen (one of the first trans people to come out in the United States), wider society was first becoming seriously aware of trans people. While media figures argued back and forth about Jorgensen, Benjamin published The Transsexual Phenomenon in 1966, the first medical textbook about trans people ever written.

Containing case studies, life stories, diagnostic advice, and treatment approaches, The Transsexual Phenomenon became the standard medical work on trans subjects, establishing Benjamin as an authority on the matter. And it was, for its time, very advanced simply for treating trans medicine as a legitimate thing. It argued that trans people who wanted medical interventions would benefit from and deserved them, at a point when the default medical approach was “psychoanalyze them until they stop being trans.” Benjamin believed this was futile, and that for those patients for whom it was appropriate, interventions should be made available.

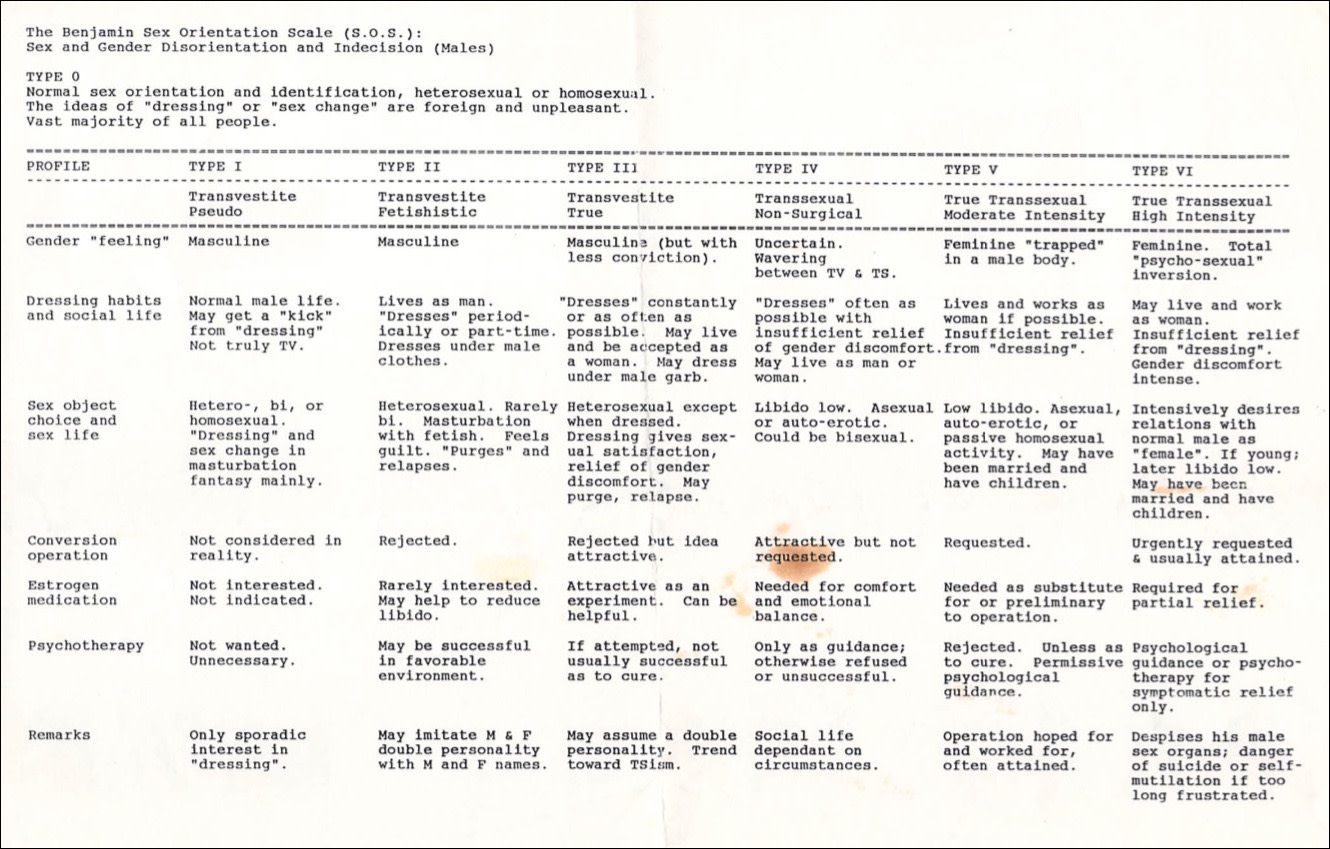

To identify whether someone was such a patient, and what treatments should be made available, Benjamin built his book around his Sex Orientation Scale, often known simply as the Benjamin Scale.

A doctor using the Benjamin Scale would first work to understand the patient, their life, and their state of mind, and then classify them into one of the six “types.” Based on that classification, the doctor would determine what the appropriate treatment options might be. For Type V or Type VI patients, often grouped as “true transsexual,” the answer was hormones, surgical procedures, and social role changes that would enable them to live a “normal life.”

But this scale, as an instrument of measurement, came with particular assumptions baked into it about what it was measuring, and what a normal life was. A normal life was a heterosexual life: a normal woman, according to Benjamin, is attracted to men. A normal life meant two, and only two, genders and forms of embodiment. A normal life meant a husband (or wife) and a white picket fence, far away from any lingering trace of the trans person’s assigned sex at birth, far away from any possibility of regret.

Further, it meant that trans women who were too “manly” in bone structure, or trans men too feminine, should be turned away at the door. It meant delay after delay after delay to ensure the patient really wanted surgery, advocating “a thorough study of each case… together with a prolonged period of observation, up to a year” to prevent the possibility of regret. It meant expecting patients to live as their desired gender for an extended period of time to ensure they would “pass” as “normal” after medical intervention — something known as the “real life test.” Ultimately, Benjamin wrote, “the psychiatrist must have the last word.”

So to Benjamin, a “true” trans person was heterosexual, deeply gender-stereotyped in their embodiment and desires, and willing to grit their teeth through a year (or more) of therapy to be sure they were really certain that they would prefer literally anything else to spending the rest of their life with gender dysphoria.

No More Ghosts

On its own, Benjamin’s notion of a “normal life” would have been nothing but laughable — and laugh is what most of my friends do when I point them to the bit where he doesn’t think queer trans people exist. But because of how widely his instrument of measurement has worked its way into systems of power, it has been deeply influential.

Benjamin’s textbook and, more importantly, his scale, became standard in trans medicine, informing the design of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) definitions of gender dysphoria and the rules of the World Professional Association on Transgender Health (WPATH) — considered (by doctors) to be the gold standard in treatment approaches. Those rules still contain a “real life” test and psychiatric gatekeeping, and the DSM only began recognizing non-binary genders as real in 2013. More broadly, public narratives of transness still tell “the story” popularized and validated by Benjamin — the trans woman “born a girl, seeing herself in dresses,” the trans man who has “always known” — even when that story does not and has never represented many of us.

The consequences for people who do not conform have been dire. People are denied access to medical care for not meeting the formal medical definition of a “true transsexual”; people are denied legitimacy in trans spaces for not “really” being trans; people are convinced by these discourses that their misery must be fake — that because they don’t fit a particular normative idea of what a trans person is, they’re not really a trans person at all, and so should go back into the closet for years or decades or the rest of their lives. All because of a tool that claimed merely to measure gender. Inside and outside our communities and selves, Benjamin’s ghost continues to wreak unholy havoc.

So what is the point of this (admittedly fascinating) psychomedical history? The point is that there’s no such thing as a tool of measurement that merely “measures.” Any measurement system, once it becomes integrated into infrastructures of power, gatekeeping, and control, fundamentally changes the thing being measured. The system becomes both an opportunity (for those who succeed under it) and a source of harm (for those who fail). And these outcomes become naturalized: we begin to treat how the tool sees reality as reality itself.

When we look at AGR, we can observe this dynamic at work. AGR is a severely flawed instrument. But when we place it within the context of its current and proposed uses — when we place it within infrastructures — we begin to see how it not only measures gender but reshapes it. When a technology assumes that men have short hair, we call it a bug. But when that technology becomes normalized, pretty soon we start to call long-haired men a bug. And after awhile, whether strategically or genuinely, those men begin to believe it. Given that AGR developers are so normative that their research proposals include displaying “ads of cars when a male is detected, or dresses in the case of females,” it’s safe to say the technology won’t be reshaping gender into something more flexible.

AGR might not be as flashy or obviously power-laden as the Benjamin Scale, but it has the potential to become more ubiquitous: responsive advertising and public bathrooms are in many more places than a psychiatrist’s office. While the individual impact might be smaller, the cumulative impact of thousands of components of physical and technical reality misclassifying you, reclassifying you, punishing you when you fail to conform to rigid gender norms and rewarding you when you do, could be immense.

The good news is that the story of the Benjamin Scale shows us that resistance is possible. We did not go quietly into the psych; we fought, we lied, we hit back, and we continue to do so. But resistance is not enough. The norms that the Benjamin Scale worked into the world are still being perpetuated. Carving out space to breathe and live is good, but those battles are only necessary if you have already lost the war.

So rather than focus on reforming AGR — adding new categories or caveats or consent mechanisms, which are all moves that implicitly accept its deployment — we should push back more generally. We should focus on delegitimizing the technology altogether, ensuring it never gets integrated into society, and that facial recognition as a whole (with its many, many inherent problems) goes the same way. Do not just ask how we resist it — ask the people developing it why we need it. Demand that legislators ban it, organizations stop resourcing it, researchers stop designing it. Forty years after Benjamin’s death, we are still haunted by his ghost. We don’t need any more.