Earlier this year, India’s largest food-delivery platform, Zomato, announced the launch of “pure-veg mode” on their app with a separate delivery fleet for “pure vegetarian” orders.1 Under this mode, Zomato’s users can get food delivered from restaurants that don’t serve any meat, and its “pure veg” fleet would not handle any meat. This mode was visually differentiated from the red branding of the company with a green user interface in the app, along with green uniforms and equipment for its delivery workers.

The announcement received widespread backlash, especially from anti-caste voices on social media like Sumeet Samos, who noted that Zomato’s visually segregated “pure veg” feature reinforced Brahmanical notions of impurity and untouchability associated with meat-eating in India.2 Others pointed out how the separation of workers through green uniforms for “pure veg” orders segregates delivery workers along lines of caste purity and could risk the safety of Zomato workers and even some customers. This is because being nonvegetarian in India is often a proxy for caste, ethnicity, and/or religious identity. Association with nonvegetarian food could lead to nonconsensual disclosure of status and risks ostracization of marginalized caste/religion customers (as well as delivery workers) in “upper caste,”3 vegetarian neighborhoods, where meat eaters often face discrimination when renting or buying properties.4

Surprised by this backlash, Zomato CEO Deepinder Goyal clarified that this feature was designed for a significant portion of its users who are particular about how their food is cooked and handled. He further elaborated that their “pure veg” feature has nothing to do with caste but is rather designed around a “spiritual” preference. Citing friends who have turned vegetarian after meditation retreats, Goyal insisted, “It’s a deeply spiritual thing. They [vegetarians] don’t want to hurt anyone. It’s the principle of nonviolence rather than anything to do with religion or caste.”5 Goyal complained dismissively that food is unduly politicized—implying, by extension, that the design of digital platforms governing food delivery has nothing to do with the politics of caste.

Zomato’s response follows a pattern where upper castes claim their lifestyles and food habits are caste-less and the moral default while dismissing any criticism of this “default” as undue politicization. Citing user studies and market research as the cornerstone of their decision and dismissing an intent to harm or hurt, Zomato seems to imply that they cannot be casteist because there was no intention to be casteist. This focus on casteist intent obfuscates how caste is woven into the social fabric of India in which the platform economy operates. A deep dive into the purportedly innocuous, “user-centered” design of three digital platforms reveals how it defaults to casteist logics that further the interests of caste and class elites while normalizing Brahmanical culture in digital India.

Preference for Purity: Zomato

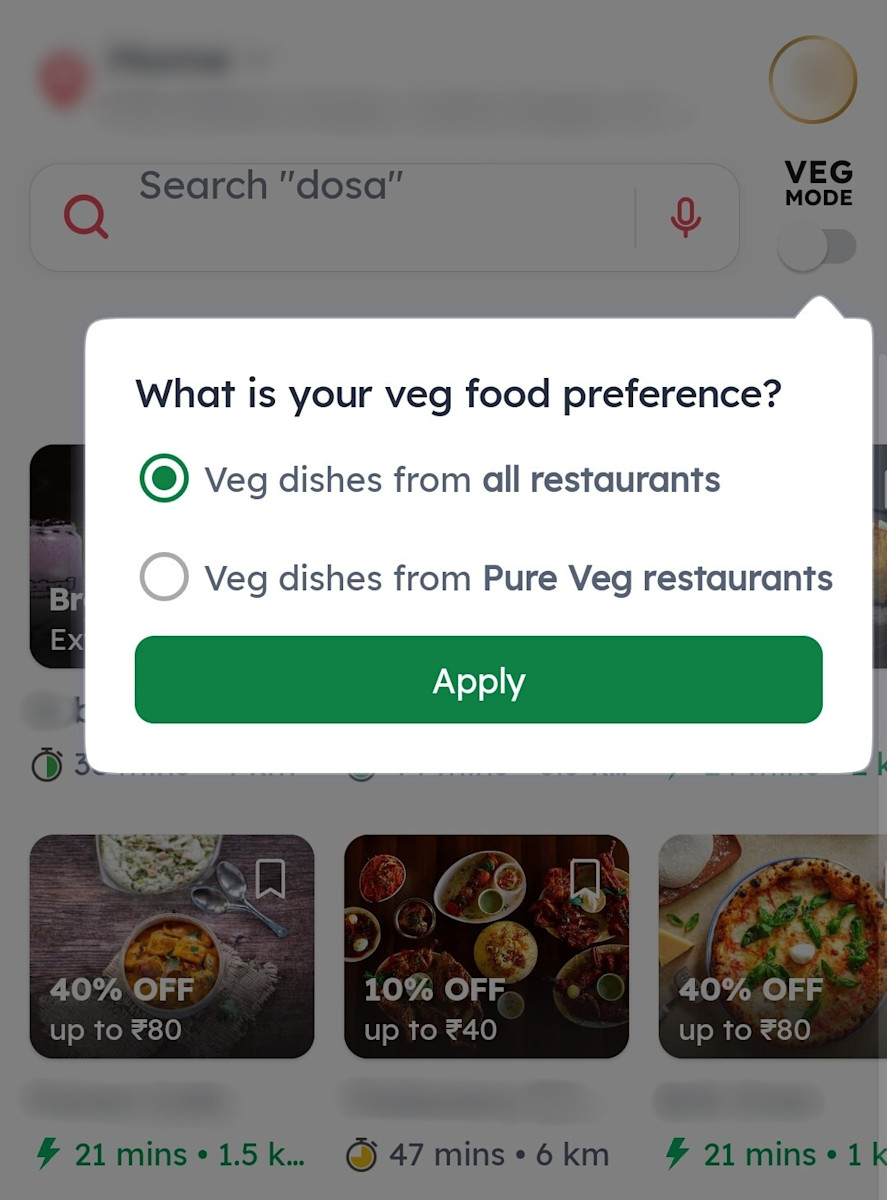

After coming under intense scrutiny, Zomato withdrew the visual differentiation of the pure-veg fleet but quietly released a “veg mode.” This feature lets users choose between vegetarian dishes from “all restaurants” and/or “pure-veg restaurants.” If the user chooses “pure-veg restaurants” in this mode, the app removes all restaurants serving meat or egg dishes; it makes the user experience “pure” by eliminating any interaction with pictures of meat dishes or eateries that might be handling meat. In this mode, the food is delivered by workers who only carry “pure veg” food.

Although food platforms justify such filters as a matter of mere dietary preference, this has roots in Brahmanical notions of purity and untouchability. Dr. Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar, in fact, traces the origins of untouchability to practices of beef eating, arguing that eating beef became the boundary between the touchables and untouchables in India, a status assigned at birth. Dalits, or “untouchables,” have historically been tasked with disposing of cow carcasses in villages. Dalit communities would then use different parts of the cow; for example, cow skin was used for leatherwork, and many would eat the cow meat.6 7 The cow, when alive, is worshipped by the “touchables,” including the vegetarians; but the same cow, when dead, becomes dirty and “untouchable” along with those who dispose of it. Thus, aspirations and claims to being “pure veg” have originated in tandem with the caste-based division of labor and are rooted in untouchability.

Aspirations and claims to being “pure veg” have originated in tandem with the caste-based division of labor and are rooted in untouchability.

As an extension of notions around beef, meat-eating overall becomes a signifier of caste status and ritual purity. The mere presence of meat threatens the purity of vegetarian foods and, by extension, those who consume them, invoking “disgust,” “dirtiness,” and “nausea” in pure vegetarians at the sight, presence, or even discussion of meat.8 The notion of untouchability and anxieties concerning caste purity in food appear in the form of fear of cross contamination. Pure-veg Hindus often refuse to use a spoon that might have “touched” meat9, to share a table with meat eaters,10 and to use a microwave where meat is heated.11 Being vegetarian becomes not just a preference but a source of superiority—often repeated in the form of equivalence between vegetarianism and nonviolence among Hindus (and Jains). These boundaries of food habits, lifestyles, and purity often shape who one can sit with, who one can marry, who one is friends with, and who one does business with.

Pure-veg preferences of upper castes are enforced by disciplining and punishing those who are non-veg. For example, some offices and schools outrightly ban meat from lunch, citing sentiments and values,12 and meat sales are often banned during Hindu festivals.13 This disgust towards meat results in the ostracization of meat eaters who face aggression and shaming in interpersonal relationships and workplaces for their food habits and their associated caste.14 Often, this also leads to violence, where suspicion of meat-eating has led to Dalits, Adivasis, and Muslims being lynched publicly.1516

Pure-veg filters are not confined to food-delivery apps and can be found across digital platforms in India. For example, vegetarian landlords and housing associations often refuse to rent or sell property to meat eaters.17 Housing platforms like NoBroker have a filter to search for “non-veg” houses.

Although Zomato claims that its pure-veg filter is supported by 80 percent users, their own data says that only 2 percent of their users are vegetarians.18 This raises the question of whose preferences and purity are centered in the design of food-delivery platforms. For Zomato, a “pure veg” filter is simply a matter of user preference, but these users and their preferences are located in a casteist context of India where notions of purity frame marginalized castes and religions as impure because of their food habits. With the “pure veg” toggle, the user interface of Zomato implicitly extends Brahmanical notions of caste purity and digitally reproduces casteist notions about food and untouchability. By visually cleansing the app from the polluting sight of meat as well as promoting delivery of pure-veg food in designated delivery bags free of contamination by meat, this platform reinforces casteist ideas that vegetarian users need to be protected from the impurity of those who cook, consume, or deliver nonvegetarian food.

Objectification for Convenience: BookMyBai

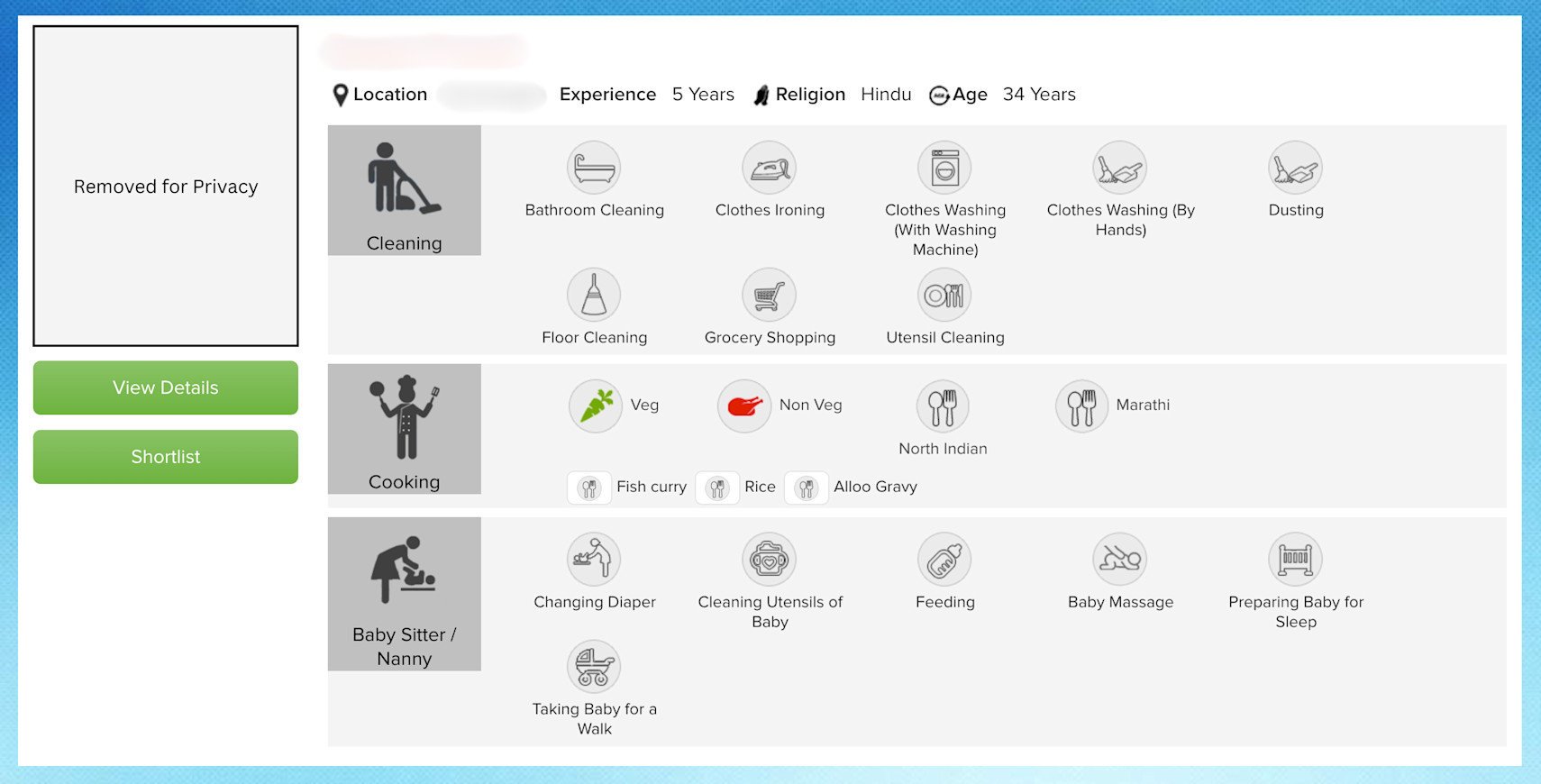

A search engine inquiry for “looking for a maid in Bangalore” usually ends up suggesting a link to a list of workers on a digital platform named BookMyBai (Bai translates to domestic help in Hindi). Clicking on this link takes you to a grid of worker images detailing their gender, religion, and ethnicity. Further, clicking on an individual worker’s profile brings up their personal details, with checklists of services they provide. It also contains personal details like their full name, native village, marital status, religion, vaccination data, and, finally, a button to hire the worker. While the platform doesn’t explicitly mention their caste, surname, and village can often be used to triangulate someone’s caste location.

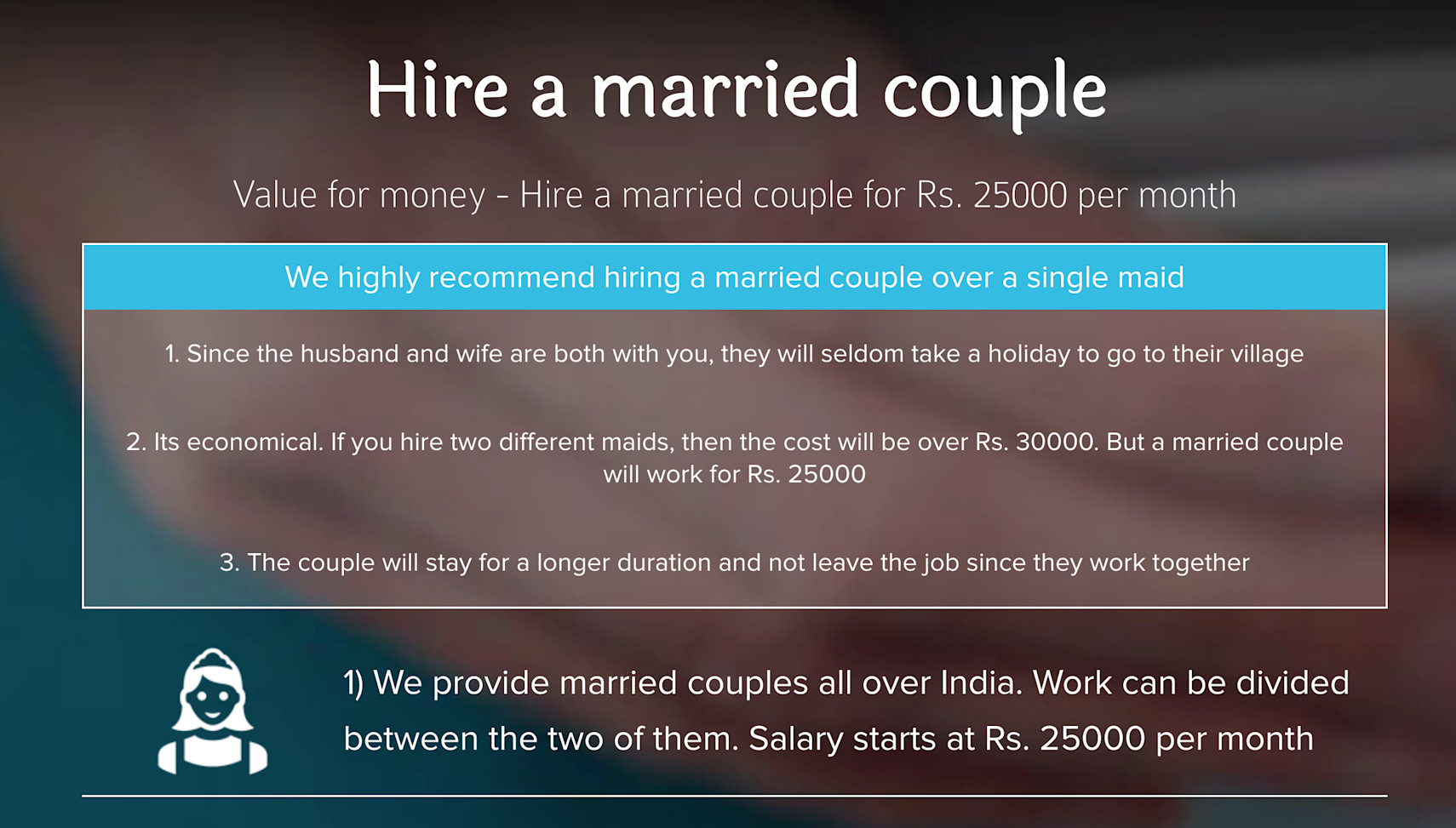

BookMyBai hawks workers who are married couples as a “two-for-one special,” noting the discounted price compared to hiring two separate workers. It frames workers and their services like a combo offer usually seen on product marketplaces—calling it “value for money.” The platform recommends hiring a couple because “if you hire two, it will cost 30,000 rupees, but a married couple works for only 25,000.” The website further elaborates on why this combo offer is great: a married couple who work together in a home are less likely to take holidays to visit their village and likely to work for longer durations as their employment is tied to a single employer, the user of this web app.

If anything goes wrong or the worker leaves, the platform promises to provide a “free replacement” of the worker, analogous to a six-month product warranty seen for commodities. With an interface and language that represents workers as commodities in a marketplace, the worker’s body is transformed into a product that can be browsed, compared, replaced, and refunded. This is done with visual design elements like the grid of workers where their private and sensitive information is made publicly available online, and the marketing copy that positions their services in the language of “free replacements” and “value for money.”

The worker’s body is transformed into a product that can be browsed, compared, replaced, and refunded.

Urban housework in India is mired in an intersection of casteism and a gendered system of labor that restricts occupational mobility—two-thirds of the domestic worker population are women, and a majority of these workers are Dalits or Adivasis who have migrated from villages.19 When upper-caste women are employed for housework, one rarely sees them performing sanitation labor, and vice versa; untouchables are rarely employed in childcare or cooking.

This is because of the caste system, where one’s place in the social hierarchy is tied to their community’s traditional occupation. A ritual hierarchy of labor, bolstered by religious scriptures like the Manusmriti, forms a close relationship between respectability and caste. In practice, this translates into forms of respectable or cerebral labor—like knowledge production, administrative, and cultural work—being performed largely by upper castes; meanwhile, manual labor tends to be done by castes further down the hierarchy. Consequently, work that is considered dirty or impure is still done largely by castes considered “untouchable.”

This casteist and sexist landscape is made further exploitative by the fact that domestic work is often underpaid, over-exploited, and subject to harassment. Domestic workers are regularly dehumanized by their employers through a rhetoric of distrust: they are often falsely accused of theft, denied leave, deprived of rightful payments, sexualized, and ridiculed in popular culture.20 Religious texts that legitimize caste also advance the view that lower castes, especially lower-caste women, are subjects to be controlled and managed to maintain the caste system.21 Under these religious sanctions on the humanity and rights of marginalized caste women, issues of underage labor, human trafficking, sexual exploitation, and workplace abuse are normalized with little to no social and legal protections for domestic workers.22 While the default rhetoric of digital platforms like BookMyBai or Urban Company is secular, and there is no explicit mention of caste or religion, these systems of exploitation and dehumanization continue to manifest in the platforms’ ethos, actions, and practices.

Specifically, BookMyBai relies on the precarity of domestic work and its casteist roots while feeding into the dehumanization of domestic workers through objectification on their platform. While other domestic work platforms and offline agencies exist, BookMyBai is distinct in how it positions itself not as a service provider but as a product marketplace—the workers being its products. In 2015, the platform ran a controversial advertisement that suggested that consumers can “gift” a maid to their wives instead of diamonds, comparing workers on its platform to objects.23 Such objectification of domestic workers echoes the historical practice of gifting marginalized-caste people as slaves as well as their traffic as indentured agricultural, sexual, and reproductive workers in precolonial and colonial South Asia.24

BookMyBai’s interface is designed for the convenience and safety of its customers. When discussing worker couples, it invokes the language of product combos and lists their weaker negotiation power as a family tied to a single employer as an advantage. Workers are objectified by rendering them as browsable entities that can be screened, filtered, and surveilled as per the needs of the customers. Meanwhile, no interface exists for workers to choose and screen their employers. The platform maintains a crowdsourced and publicly available blacklist of workers based on customer complaints with their name, photograph, location where they were last seen, and a description of what they were doing. Workers cannot publicly report and document abuse from the customers, and there is no blacklist of customers akin to the list of blacklisted workers. The platform’s policies center the employers and their concerns but only explicitly mention workers’ rights once in its terms and conditions—noting that employers cannot torture or abuse workers, or change salary or workload. In practice, BookMyBai’s interface centered on the customer-as-user extends casteist logics of indentured slavery and servitude by constricting the rights of the laboring classes/castes in India.

Surveillance and Control as Safety: MyGate

The popular platform MyGate is used to manage the flow of people in gated residential societies in India. The app’s “Daily Help Management” page centralizes the process of hiring, payments, issuing gate passes, and monitoring the location of domestic and service workers for residents of these gated communities. MyGate maintains a database of workers affiliated with the gated residence, and if a new worker wants to work within that community, they first need to be registered by their employer with the app. MyGate requires workers to submit a list of legal documents in order to be verified, registered, and approved for work. Workers are not made aware of rights and protections (if any) related to the collection and circulation of their data on the platform.

This intrusive data collection enables granular monitoring and control of worker movement. Residents are notified when workers on their list enter and exit the community. They are also able to access detailed logs of worker visits to any other household in the community. When a worker visits someone else’s home and skips their house, a notification to the resident is triggered. These features are marketed by the platform as a way of tracking worker attendance and to help employers calculate salaries more effectively. The customer-as-user interface also allows the resident to rate and review workers on the platform across different parameters like service quality, punctuality, and attitude. Unlike ride-sharing platforms, this rating feature is exclusively available to employers. Workers are only given a six-digit gate pass, and all other aspects of their movement, employment, and payment on the app are handled by their employers or the residential governance associations.

Housing in urban India is segregated across caste and class lines. Members of upper castes, who tend to have higher class mobility,25 live in affluent colonies and communities with other upper-caste residents, away from the caste oppressed. Marginalized castes are often discriminated against when renting and buying property in gated communities with a higher proportion of members from upper castes; for example, townships made exclusively for Brahmins, Jains, and other upper castes are a common phenomenon.26

Gated communities dovetail with the caste and class anxieties of upper castes. These communities create a physical barrier to protect the space and inhabitants inside the gate with well-built homes, swimming pools, and parks. These gates are manned by security guards, often themselves from marginalized communities, who must follow strict protocols for entry and exit into the community. Residents of these gated communities nevertheless rely on the critical labor of castes who do their domestic work, sanitation work, home services, delivery work, and more. Within the gated communities, workers are not allowed to sit in hallways and parks, are denied access to lifts, and denied access to sources of drinking water and toilets.27 As one viral circular from a gated community suggests, their presence can make residents feel uncomfortable; mere contact with their bodies pollutes the sofas, lifts, parks, and hallways.28

This space of contact—the gate—is mediated by casteist anxieties of breach, threatening their safe caste-class bubbles, on which platforms like MyGate capitalize. A cofounder of MyGate declared that a gated community should feel like living on “an (army) base”—where the movement of people, especially workers, can be monitored and controlled. Such an imaginary, in fact, emerges from a logic of maintaining boundaries of caste that are often enforced through militarized modes of social ordering in India. For example, the violence against inter-caste couples or Dalit grooms mounting a horse during their wedding (traditionally seen as a symbol of caste honor and status) continues to be on the rise as it is perceived as a transgression of caste boundaries.29 Oppressed-caste people, especially Dalits, are often humiliated, punished, or even killed for simply asserting equality. In India, the police are an extended apparatus of the status quo often used to enforce caste boundaries, where members of some marginalized castes like Vimukt (also known as denotified tribes) communities and Muslims are regularly harassed, surveilled, and imprisoned by the police.30

Gate-management and security apps like MyGate became popular during COVID-19 lockdowns.31 Concerns around contact and contamination from COVID aligned well with practices of untouchability and served as a pretext for increased casteism and casteist surveillance against marginalized caste workers.32 Marginalized castes were treated as carriers of disease to be monitored, surveilled, and controlled for the “safety” of the residents.33 Although it is advertised as an “end-to-end society management” service with features like gate management, marketplaces, community message boards, and worker management, MyGate is fundamentally a surveillance system for workers who are seen as suspicious or untrustworthy. For example, communities with MyGate or other digital security platforms often check the bags and personal belongings of workers at the gate. Workers need notes from employers if they are carrying anything “unusual” with them, or else they are held up by security guards. The app further criminalizes and scares the workers with hiring contingencies such as police verification.34

While paper logbooks and intercom systems historically surveilled worker movement in gated communities, MyGate creates an extensive, real-time, and public record of workers. It records every movement of the worker within the residential compound, the employers’ perceptions of the worker, and their working hours and salaries. The worker has no choice or information about what aspects of their life, livelihood, and movement are tracked, who they are shared with, and what they are used for.

At the same time, MyGate allows residents disproportionate oversight and control over workers’ livelihood and movement: a worker’s entry pass can be revoked at any point in time, and they can be harassed for taking an unannounced emergency leave or given poor ratings that reduce their employability.35 The workers are left at the mercy of the employers; MyGate has no interface for the worker and has no grievance redressal mechanism for workers. Indeed, the platform is designed against workers having any control over their livelihood and their relationships with customers. This asymmetry between the purveyors of data collection versus those subjected to data collection on apps like MyGate is continuous with historical caste politics, where book-keeping and record-keeping have traditionally been Brahmanical professions dominated by upper castes who keep track of the larger population and subjects of the state.

Extensive surveillance of workers stems from Brahmanical notions of distrust that use the language of security to maintain boundaries of caste within gated communities. Boundaries of touchability, selfhood, and caste are maintained through the app’s interface, which offers a new mechanism for worker control through calendars, logbooks, movement records, ratings, and reviews. Workers’ autonomy is traded for residents’ sense of security to maintain the user’s anxieties of caste and class.

Defaulting to Casteism

When one digs deeper into the notions of preference, convenience, and safety advanced by digital-service platforms in India, casteism emerges as the default logic operating behind these terms. Caste itself is a technology of social ordering that operates on economic, social, and cultural practices of exploitation and dehumanization. This system then becomes fertile ground for the growth of Brahmanical control over the platform economy through digital technologies.

Caste itself is a technology of social ordering that operates on economic, social, and cultural practices of exploitation and dehumanization.

The rhetoric and pitch of digital-service apps suggest they offer convenient and essential services for the “public,” but the normative assumptions and worldviews designed into digital service apps are largely upper caste and upper class. The ecosystem of technology startups in India looks to “disrupt” the markets by arguing for efficiency or addressing “user needs,” but their user base is a small demographic in India that can afford the taxation, delivery, and service rates of these platforms to access key services from the comfort of their homes. In fact, the usage and market valuation of these platforms surged during the COVID-19 pandemic, and the workers who provided services through these platforms were designated as “essential” or “frontline” workers during the lockdown. The title of “essential worker” does not translate into how this workforce is seen and valued in the design of digital platforms. While BookMyBai focuses on designing a convenient user experience for customers who want to hire domestic workers, the entire economy of domestic work itself operates on the dehumanization and devaluation of oppressed castes and their labor. Zomato continues to face protests from its workers over wages and working conditions, including harassment on the job.36

Consequently, the imagined and real user in the design, marketing, and funding of these apps is one who is upwardly mobile, urban, English speaking, and financially secure. Caste strongly correlates with class in India, where upper castes are overrepresented in the top 10 percent and middle 40 percent of the population who own 90 percent of the wealth.37 In the name of user preference, convenience, and security or safety, these platforms not only rely on casteist anxieties of the classes they serve but also validate and reinscribe them.

For example, a notebook that logs which people enter the building and leave has been a norm in newer and lavish gated communities, but MyGate takes this one step further to create a permanent public database of all aspects of a worker’s livelihood. According to the ethos of MyGate’s founder, the user within the gates of a residential “army base” is the one who needs protection from the outsider enemy who does not reside in elite gated complexes and needs monitoring through the app. Caste is a system of domination and power, and it manifests as deep-rooted distrust in people who don’t look like or behave like a particular caste (and class) group. India has a long, casteist history of policing and surveilling oppressed caste communities like the Vimukt castes, once classified as “criminal tribes,” who continue to face criminalization by the state. Such distrust of a particular group of people, especially those who are poor and who perform service labor for affluent and “respectable” households, is at the heart of how Brahminism operates in everyday cultures of India.

Dietary habits have generally been a way of enforcing social segregation, which in the context of India is embedded in caste relations. In the case of Zomato, the customer can now curate their exploration of restaurants in ways that align with their notions of purity, whereas previously they needed to step out of the house and onto the street, where all kinds of food are served, then select their “pure veg” restaurant of choice. When confronted with pushback against their “pure veg” feature’s relationship to caste, the CEO of Zomato claimed that his company and team have the “purest form of indifference to any casteism and religious biases” as they “don’t have a historical context” of caste.38 Such responses obscure the deep entrenchment of casteism in the notions of purity rooted in untouchability. In Zomato’s design, denial of accountability to caste enables it to perpetuate Brahmanical worldviews of a particular group’s dietary preferences as a neutral, “casteless” norm couched as “user preference” when, in fact, it is rooted precisely in caste.

A deeper anti-caste examination of popular definitions of usability and user experience reveals the ecosystem behind the screen that advances and normalizes Brahmanical and casteist cultures of consumption in India. Uber, Ola, Blinkit, Zomato, Swiggy, BookMyBai, and Urban Company, among others, are companies that rely on filtering and a division of labor that is already organized by caste in the economy of India. While the service workers in these companies traditionally come from caste-oppressed communities, the engineers, managers, and designers working at these companies come overwhelmingly from dominant or upper castes. Technical, management, and design education in India also does not engage seriously with caste; as a result, it reproduces the Brahmanical sensibilities seen in these platforms.

Professional, white-collar circles that design, build, and sell such apps are often mired in the rhetoric of meritocracy, which denies the existence of caste and casteism. While several digital platforms use the language of diversity and empowerment in their marketing, there is no mention of caste across different policies for employees, board, and service workers on these digital platforms.39 Obfuscation of caste effectively helps produce environments where casteism emerges as the default because it is seen as a natural order of things in business, technical, and consumer logic.

The myth of neutrality in technology has long been dispelled by oppressed peoples around the world, but it is equally important to understand how oppressive structures organize our digital worlds and how digital platforms, in turn, are changing the nature and forms of oppression. Denial and obfuscation of caste by digital platforms serve the status quo and empower it. Caste is not something that can be solved by an app or a feature/button/filter; nor can it be wished away by designers by focusing on the mythical “casteless” user. Understanding how the material and social realities of caste are intertwined with digital platforms is essential if we are to dismantle technologies that reproduce and expand caste hierarchies. In a society where casteism remains default, the annihilation of caste must be intentional.

1. Deepinder Goyal, “India has the largest percentage of vegetarians in the world,” Twitter post, March 19, 2024, x.com.

2. Jessica Rajan, “‘All Riders Will Wear Red’: Zomato Rolls Back Green Uniform for Pure-Veg Fleet amid Social Media Backlash,” Economic Times, March 20, 2024, economictimes.indiatimes.com; Sumeet Samos, “Zomato Row: In a Caste-Coded Society, the Politics of Who Touches Your Food,” Quint, March 20, 2024, thequint.com.

3. In this article, “upper caste” refers to castes higher up in the caste hierarchy, often belonging to the top three varnas of the Brahmanical version of the caste system. It can also be defined as castes other than those belonging to SC, ST, OBC, and DNT classifications. The term “Savarna,” on the other hand, includes upper castes and OBC communities as they are all part of the varna system, unlike the Dalits or Adivasis. It is important to note that the dynamics of caste hierarchy are graded, meaning that each caste higher than the other practices casteism toward the caste lower in the hierarchy. Caste is highly contextual to a region and, most importantly, operates at the jati level, where many jatis make up a particular varna like OBC or SC. Thus, a higher-caste SC person practices casteism against jatis lower in the SC hierarchy than them, while an OBC person benefits from caste privilege compared to SCs and practices casteism toward SCs. See B. R. Ambedkar, “Castes in India: Their Mechanism, Genesis and Development,” paper presented May 9, 1916, at Columbia University.

4. Haima Deshpande, “Food Apartheid: Non-vegetarians Not Allowed!,” Outlook India, February 7, 2024, outlookindia.com.

5. Jocelyn Fernandes, “Have 75% Veg Orders, the Decision for ‘Pure Veg’ Fleet Came after Survey, Says Zomato CEO Deepinder Goyal,” Mint, March 27, 2024, livemint.com.

6. Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar, “Untouchability, the Dead Cow and the Brahmin,” in The Untouchables: Who Were They and Why They Became Untouchables? (Maharashtra: Navayana Publishing, 2009).

7. B. R. Ambedkar, Beef, Brahmins, and Broken Men: An Annotated Critical Selection from The Untouchables (New York: Columbia University Press, 2020).

8. Dolly Kikon, “Dirty Food: Racism and Casteism in India,” Ethnic and Racial Studies 45, no. 2 (August 23, 2021): 278–97.

9. Bhavya Sukheja,“What If Same Spoon Is Used?’: Sudha Murty’s ‘Veg-Non Veg’ Remark Divides Internet,” NDTV, July 26, 2023, ndtv.com.

10. Abhinay Lakshman, “IIT-Bombay Mess Sanctions Segregated Space for People Eating Vegetarian Food,” Hindu, September 27, 2023, thehindu.com.

11. “As a Vegetarian, How Can I Deal with Microwave Ovens Smelling of Meat and Fish?,” Workplace Stack Exchange, n.d., workplace.stackexchange.com.

12. Deepak Upadhyay, “Converting Others Through Food’: UP School Principal Expels Class 3 Student for Bringing Biryani,” Mint, September 6, 2024, livemint.com.

13. Aparna Alluri, “Meat Ban: India Isn’t Vegetarian but Who’ll Tell the Right-wing?,” BBC, April 8, 2022, bbc.com.

14. The Big Fat Bao, “The Subtle Brutal Flavours of Casteism in My Family Kitchen,” BehanBox, November 10, 2023, behanbox.com; Aarefa Johari, “Liberal ‘Hindu’ Newspaper Reiterates No-Meat Policy in Office, Sparks Debate on Vegetarian Fundamentalism,” Scroll, April 18, 2014, scroll.in.

15. “Two Adivasi Men Allegedly Lynched on Suspicion of Killing Cow in Madhya Pradesh,” Scroll, May 3, 2022, scroll.in.

16. Somya Lakhani, “A Boy Called Junaid,” Indian Express, June 5, 2019, indianexpress.com.

17. Deshpande, “Food Apartheid.”

18. Fernandes, “Have 75%.”

19. Maitreyi Krishnan, “Being Domestic Workers in India: No Rights in the Face of Triple Oppression of Class, Caste and Gender,” All India Central Council of Trade Unions, n.d., aicctu.org.

20. Rini Barman, “How Indian Pop Culture Fetishises the Maid,” Dailyo, June 24, 2018, dailyo.in; Ravikant Kisana, “Laughing Like a Savarna,” Swaddle, June 30, 2023, theswaddle.com; Madhavi Shivaprasad, “Humour and the Margins: Stand-Up Comedy and Caste in India,” IAFOR Journal of Media Communication and Film 7, no. 1 (October 2022).

21. “Casteist Verses From Manusmriti – Law Book of Hindus,” Velivada, May 42, 2017, velivada.com.

22. Harsh Mander, “Underage Children as Domestic Workers: Middle-Class India’s Greatest Shame?,” Scroll, April 16, 2015, scroll.in; Geeta Menon, “Undefined Roles, Dire Realities of Domestic Work,” Deccan Herald, July 14, 2024, deccanherald.com.

23. “The Advert That Said: ‘Gift Your Wife a Maid,’” BBC News, November 3, 2015, bbc.com.

24. Andrea Major, “Unfree Labor in Colonial South Asia,” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Asian History (April 2019).

25. Nitin Kumar Bharti, “Wealth Inequality, Class, and Caste in India: 1961-2012,” Ideas for India, June 28, 2019, ideasforindia.in.

26. Sanjana Sree Manusanipalli and Sandeep Pandey, “Exclusive Brahmins Township: Of Hindutva, Casteism and Segregated Housing Societies,” Counterview (blog), March 2, 2023, counterview.net.

27. Trends Desk, “Classist Nonsense’: Bengaluru Housing Society Asks ‘Maids to Not Use Common Areas,’ Twitter Erupts,” Indian Express, June 23, 2023, indianexpress.com; Tiasa Bhowal, “Fine for Using Main Lift: Hyderabad Housing Society Notice for Helps Sparks Row,” India Today, November 28, 2023, indiatoday.in; Aditi R., “Chennai: House Workers Can’t Use Loos They Clean, Approach the Government,” Times of India, July 10, 2021, timesofindia.indiatimes.com.

28. Vibin Babuurajan, “Residents of a Bangalore Society Confusing Class and Being a Classist🤮,” Twitter, June 20, 2023, x.com.

29. Niha Masih, “Riding a Horse Is Tradition for Indian Grooms — Except Dalits, Who Face Caste Violence. One District Is Fighting Back,” Washington Post, March 2, 2022, washingtonpost.com.

30. Nikita Sonavane et al., “Building Blocks of a Digital Caste Panopticon: Everyday Brahminical Policing in India,” Logic(s) 20 (2023), logicmag.io; Shivangi Narayan, “Guilty Until Proven Guilty,” Journal of Extreme Anthropology 5, no. 1 (September 2021).

31. Nandita Mathur, “Covid Triggers Spike in Demand for Security Apps for Gated Societies,” Mint, September 7, 2020, livemint.com.

32. Priyali Sur, “Under India’s Caste System, Dalits Are Considered Untouchable. The Coronavirus Is Intensifying That Slur,” CNN World, April 2020, edition.cnn.com.

33. Romita Saluja,“How COVID-19 Worsened Hardships of India’s Domestic Workers,” Wire, thewire.in.

34. Prajitha G. P., “Domestic Work in the Platform Economy: Reflections on Awareness of Workers Rights,” GenderIT, April 8, 2020, genderit.org/articles/domestic-work-platform-economy-reflections-awareness-workers-rights.

35. Tanya Maheshwari, Sureet Singh, and Itika Sharma Punit, “The Apps Were Designed for Home Security. They’re Being Used to Watch and Harass Domestic Workers,” Rest of World, August 14, 2023, restofworld.org; Gopal Sathe, “On Maid-Rating Apps India’s Entitled Baba-Log Hit New Low,” HuffPost, November 19, 2018, huffpost.com.

36. Express News Service, “Zomato Workers in Kochi to Go on Three-day Strike From March 23,” New Indian Express, March 13, 2024, newindianexpress.com; Impact Live, “Patna में Zomato, Amazon, Swiggy का Delivery हुआ बंद?,” YouTube, January 28, 2025, youtube.com.

37. Shreehari Paliath, “Income Inequality in India: Top 10% Upper Caste Households Own 60% Wealth,” Business Standard, January 14, 2019, business-standard.com.

38. NDTV, “Zomato Founder Deepinder Goyal Explains the Idea Behind ‘Pure-Veg’ Fleet | NDTV Indian of the Year,” YouTube, April 6, 2024, youtube.com.

39. “Governance | Board, Committee and Composition: Zomato,” Zomato, zomato.com.