Mario Perez is a community organizer and a Resisting Surveillance Fellow with Community Justice Exchange (CJE), where he builds power to abolish data criminalization, surveillance, and all forms of social control imposed on migrant communities.

We spoke with Mario about his experiences with and organizing against Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s (ICE) deportation case management program, the Intensive Supervision Appearance Program (ISAP), also described by ICE as “Alternatives to Detention” (ATD). Through ISAP, ICE uses various surveillance technologies to track 185,000 immigrants and families. Among other methods, ICE monitors people in ISAP via GPS (global positioning system)-enabled electronic ankle shackles and via SmartLINK, a cell phone app that uses GPS, facial recognition, and voice recognition technologies.

Hannah Lucal: We first met working on issues of ICE surveillance. Before we get into your work, can you share a bit about who you are and how you got into organizing?

Mario Perez: I am a queer, gay man. I’ve lived in Southern California pretty much my whole life. I arrived in the US when I was five, so pretty much grew up undocumented. It wasn’t until DACA [Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals] that I saw some sort of immigration relief, and then that was taken away from me. With DACA, you have to be the perfect DREAMer.1 No mistakes are allowed. Because of a couple of issues that I ran into, I was basically dropped from DACA.

After that, during the Trump administration, everybody was at risk for detention and deportation. The word “criminal” was expanded in the immigration context to include anybody that didn’t have any kind of status. I live an hour away from the biggest detention center in California, Adelanto [Detention Center]. That facility has, like, two thousand beds. They were doing a lot of in-community arrests during that time, and they [ICE agents] showed up at 6:00 a.m. and took me to Adelanto.

After six months, I was finally released on bond, but was placed on ATDs [Alternatives to Detention, also known as the Intensive Supervision Appearance Program or ISAP]. When you’re incarcerated, you’re so desperate that any kind of condition placed on you, you’re going to take. I didn’t know really about ATDs—I didn’t know what was going to happen. I knew that conditions inside of detention were really, really horrible. So the first thing that I started to organize around was humanitarian support for folks being released.

I was on ATDs for about four years. First, I was on an ankle monitor for about seven months. It was—it was terrible. It was having to carry my batteries everywhere. It was the shame of having this thing on your ankle and folks thinking you are this or that. I had weekly office check-ins, home check-ins, and my life was very restricted. At the end of the day, they’ll dehumanize you, that’s the purpose of ankle monitors.

Finally, I get a call one day, and it’s my case manager. Mind you, before that, I had asked several times, “When is this going to be taken off? I’m always on time. I’ve been doing everything you ask. I’ve given you my passport like you requested, and nothing.” So he’s like, “Hey, can you come in? We’re going to take the ankle monitor off and put you on this app.” And I’m like, Oh my God, this is great, because he made it sound like the best thing. I’m like, Finally, I can—shit—do simple things like wear shorts without feeling any kind of shame.

I was placed on the SmartLINK app for about three years. I wasn’t aware of all of the mental health harm it was causing until I was asked to participate in the Tracked and Trapped report, which was put together by CJE, JFL [Just Futures Law], DWN [Detention Watch Network], and others. I was asked, “Tell us how you feel.” That was the first time that I had actually said, “Well, this has been horrible. I didn’t know that I was going to have to build my whole life around a program. That my livelihood, my appointments, my daily life would all have to work around this. And they could punish me for any little thing.”

That’s where I decided, I need to share what happened with me, and support people in these programs.

Hannah: Thank you for sharing that. I really appreciated getting to support the Tracked & Trapped report through work I was doing with JFL at the time. Something that really stuck with me is that the harms—and lasting trauma for many people—are not a side effect of the program, they’re the purpose, like you said. Through that report, thirteen organizations and many community members also showed that it’s almost impossible to have a job, care for family, leave the house, et cetera while being watched. I’m curious if you want to share more about what you expected with this program compared to what you experienced.

Mario: I remember asking the ICE officer who put the ankle monitor on me, “How long am I going to have this?” And he said, “You would have to ask a judge.” By then I was already in BIA [Board of Immigration Appeals], so there was no court. There was no judge. I knew something was wrong, but I didn’t understand.

Going into the ISAP office for the first time, they played this video, and there’s signage that says, If you need this, if you need that, let your case manager know. You hear “case manager,” and you think, Oh, they’re here to help me, when in reality, that’s not what it is, right? Let’s call it for what it is: they’re not there to support you, they’re there to deport you. We need to call these programs and tech for what they are, which is deportation case management. That is the only way to understand what they’re there for.

Hannah: Yes. I remember you talked in the Tracked and Trapped report about how some people might be hesitant to talk about their experiences in ISAP because of the way that it’s framed by ICE. Could you share more about why you choose to talk about it?

Mario: Being in the program, I was kind of shy to speak about it because here I am, I have the privilege of being released and with my family and able to fight my case from the outside, but there are friends that are still incarcerated. I have this weird feeling that I shouldn’t speak up, like, what else do you want? It wasn’t until the Tracked and Trapped report that I saw actual organizations and folks saying, “This idea that was sold to you is not real.” Just understanding that it’s just another arm of this deportation machine made me want to really share my story.

People live in fear, and for the longest time, I lived in fear too. I got phone calls at, like, 2:00 a.m., “There’s something wrong with your ankle monitor, you need to report in the morning.” There isn’t, like, “By the way, do you have work, do you have school, do you have children?” It’s like, you need to be here or else.

I realized how isolated I had become, which is what they want, right. They want to make it as difficult as possible to the point where you’re on the verge of giving up. You’re being cut off from the world, the jobs you’re able to get—that pool becomes smaller because you have check-ins; you have these devices on you.

Hannah: Can you talk about the role of the company BI Incorporated that sells the various ISAP technologies and that also manages the whole ISAP program for ICE? How do the ISAP technologies work?

Mario: BI, it’s part of the GEO Group, which is in charge of detention centers like Adelanto. They’re using ankle monitors, the SmartLINK app, telephonic check-ins, and the VeriWatch. The ankle monitor, it’s GPS, basically tracking you everywhere you go, making sure you don’t leave the region where they have designated you need to be at.

They try to make it sound less intrusive, but the more streamlined they make technology, the more data they’re collecting from you. They went from an ankle monitor to having access to your cell phone. With SmartLINK, we don’t know all the information they’re collecting. Last year came the VeriWatch. It’s a brick. There’s no chance somebody would look at that and say that is an Apple Watch or Android watch. And it’s like, No, that’s not what we’re demanding.

Hannah: Speaking of demands, could you talk more about the focus of your organizing?

Mario: The first anti-surveillance project that I was fortunate to work on with the support and resources from CJE was the creation of the Resist Surveillance Network. I had amazing relationships with other directly impacted leaders and organizers who had also experienced ICE surveillance but had never really discussed the impacts of these programs in our lives. We knew there were other folks in our networks who were currently facing ATDs and we wanted to build a space for solidarity, to break the isolation, and to use our lived experiences to raise awareness and push back. We met for four months and shared this amazing space where we invited guest speakers to provide political education. The best part of this experience for me were the conversations during our meetings. It felt like we were building this small but mighty army of humans who had become politically aware and were ready to combat ICE tech and surveillance.

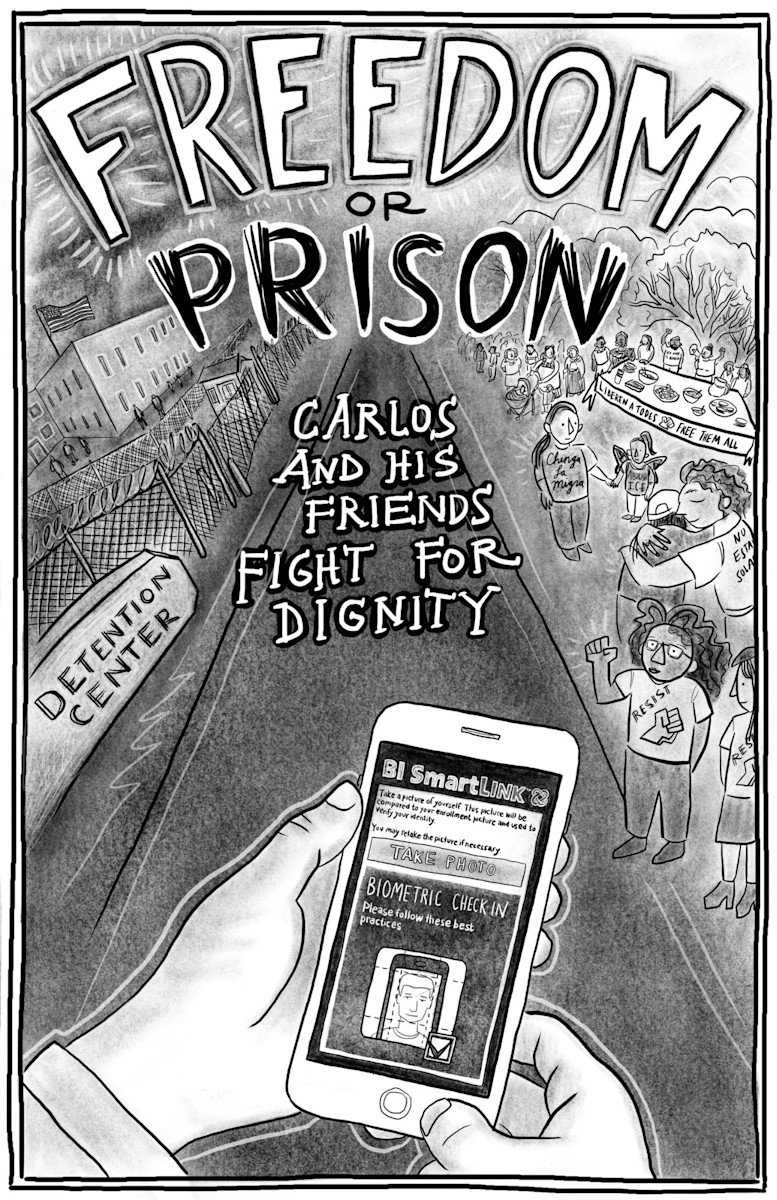

My work recently has been creating narrative [resources] for organizers and the public. CJE has a cohort of six grassroots organizations across the country who are resisting “alternatives to detention” (ATDs). We heard a lot from ICE and B.I. Being able to create work like the zine, we’re starting to hear from impacted folks and the harm that it’s caused.2

The other reason has been to show nonprofits that are tempted by receiving federal money to partake in case management—this is not the answer, right? These programs do not need to go to nonprofits under the guise of trauma-informed case management. The statement I pose to them is, you are becoming enforcement by taking on this work. It doesn’t matter how friendly you make your program. If somebody has an emergency and cannot come to their check-in, you’re going to report it, right? You’re not going to say, “Oh, this is a community member, we’re going to give them a pass.” Don’t give me any of that BS. So, I haven’t heard from them about the zine yet, but I would love to. [Laughter]

Hannah: It’s telling how many organizations are going to profit off this surveillance or justify continued surveillance through this program. How did you land on a zine?

Mario: We wanted something to hand out at actions, to show what’s happening while making a political education statement. The zine is a compilation of stories. You follow this character who becomes fed up with his experience on ISAP. It was really important to tell the story of how folks become politicized. But also, that there is hope, there is community who will support you, whether it be a de-escalation campaign to try and get you off the program to just being there to hear you talk about how awful it is.

Hannah: What kinds of risks are possible and what limitations are people facing as they’re choosing to organize around this?

Mario: You technically do not have any rights when you’re enrolled in ISAP. They operate on fear tactics. A case manager could have a bad day and take it out on you, and that’s it, you’ll be reported to ICE.

The limitations go hand in hand with the risks. The last thing anybody wants is to land back in detention. Let’s say somebody is on the SmartLINK app, right? If I were to push back, they could put an ankle monitor back on me, or they could report this to ICE, and that could potentially put me back in detention. These are the actual threats that they make. I did not really push back a lot because I had already lost my asylum case. I was already on the [US Court of Appeals for the] Ninth Circuit, so my risk would be a lot higher.

We should never ask people to take those risks unless they’re comfortable. Because they’re going to operate however they deem necessary, and it’s not going to be in your favor.

Hannah: You’re talking about how people in ISAP do not have rights. What needs to change in how we talk about tech and surveillance? Do you want to say more about your political vision?

Mario: My political vision would be to abolish all monitoring, all surveillance. Folks just do best when they’re left alone, and that’s a fact.

I am around a lot of people and families who have been forcibly enrolled on ISAP. I see people living in fear, missing family events, missing out on life because of technologies, fear. I get very sentimental—about the last few years and what that’s meant for me personally.

On ISAP, you do not expect privacy. That’s why you become so isolated, because you become so self-aware that you lack so much privacy—that almost puts others at risk. Even things like dating, right? If we’re going to be honest, dating on an ankle monitor is not cute. [Laughter] If you are trying to build a relationship or a friendship, these things are going to have to be discussed, right? And then comes those weird feelings and questions like, Are they watching us right now, through your phone? Why do you have this ankle monitor? We can’t go on this date here.

Hannah: It’s impacting your relationships and your ability to make connections—

Mario: Yes. Or going on vacation—if you fly with an ankle monitor, you are taken to secondary inspection right away. I would like people to understand that it penetrates every single aspect of your life.

Hannah: I’ve heard people talk about it as digital detention. It’s like, they just bring the detention to your everyday life in this technological form.

Mario: Exactly. It’s like, you need to tell me where you’re from, what you’re doing, what your thoughts are. They get in your head, which holds you to their standards. That’s been difficult.

I have so much information from my organizing on my phone that is readily available for them to access that it became scary. Also in mixed-status families, you don’t know if they’re listening and they’re going to report this. There are things that folks on ISAP cannot afford, and we talk about how do we protect ourselves, stay safe. It’s this whole other monster.

Hannah: How has your relationship with technology changed after being subjected to ICE surveillance?

Mario: I’ve been very careful with what I share on my socials. If I participate in actions, I don’t share where I’m at. At the same time, what I tell people is, power over chaos, right? This is not meant to create chaos, fear. It’s just to look at what you’re doing because we know they’ll use anything against you. It’s a matter of navigating safely without creating that fear that a lot of us felt earlier.

Hannah: Power over chaos, I never heard that.

Mario: We’re dealing with so much heavy shit, with so much—really huge corporations and systems. And so this is the way that we can, at least, keep some control over what can or cannot happen to us.

1. DREAMers are immigrants who arrived to the US as children and who would gain legal protections under the proposed Development, Relief, and Education for Alien Minors Act.

2. Mario is referring to the zine Freedom or Prison: Carlos and His Friends Fight for Dignity, published by Community Justice Exchange.