The question must be, “Is this expression oppositional or is it acquiescent? Does it challenge what needs to be challenged or does it roll over and play dead?”

— Mumia Abu-Jamal

Beware, my body and my soul, beware above all of crossing your arms and assuming the sterile attitude of the spectator, for life is not a spectacle, a sea of griefs is not a proscenium, and a man who wails is not a dancing bear.

― Aimé Césaire

Cameras are not unprejudiced empty objects; they possess a history of their own. When you pick one up, by chance or by choice, you hold an object as complex and storied as the technological innovations that led to its first appearance. Histories of conquest, colonialism, and slavery structure everything around us, including the decision to use a camera. The photographer can capture the wonders of the world by using this tool for artistic expression or as a weapon. These creative and violent potentials make the camera and the images it generates potential hegemonic messengers that aid oppressive power. In order to understand some of the more insidious manifestations of propaganda at play here, we should look at how colonizers and enslavers produced images of their victims before the advent of the camera. Our starting point, the US origin story, makes an illustrative case study.

In US schools, students are taught the national mythology of the Pilgrims’ arrival in “America” from Europe. A quest for religious purity drove this fervent group of settlers out of England to Holland and out of Holland to the so-called New World. The old tale that the early pilgrims “landed on Plymouth Rock” paints a picture of a harmless group of people seeking refuge from religious persecution. They saw their settlements and their tactics as justified by God. This rationale was a part of their identity and self-mythology, an idea which would prove immeasurably harmful to the world.

The Pilgrims faced a less-than-ideal departure from Leiden in the province of South Holland thanks to financing woes, limited resources, overcrowding, and delays. Ultimately they made landfall far off course from their intended destination near the mouth of the Hudson River, facing unwelcoming weather conditions. An epidemic that had been brought over by Europeans that preceded their arrival had devastated much of the area’s Native inhabitants. This was a “wonderful plague” for colonial powers who saw mass death and depopulation as evidence of divine intervention. Still, the Pilgrims themselves battled death and disease while they strove to establish themselves amid the ruination they had effected. Tensions with Indigenous tribes wrestling with their desire for more resources led to conflicts with the Pilgrims. Omitted from the popular Thanksgiving myths is that early settlers lost so many of their own people during their first winter that they practiced night burials and disguised their dead to hide their decreasing numbers.1 The Pilgrims’ relationship with dead bodies was partly one of utility already, as they desecrated Native homes and graves, and occupied places they had found strewn with those who had succumbed to disease. William Bradford, leader and eventual governor of Plymouth, noted the Native mortality, observing: “Not being able to bury one another, their skulls and bones were found in many places lying still above the ground where their houses and dwellings had been.” The settlers wanted more for their own dead.

These initial encounters with mass death framed how the European settlers related to the demise of the other, who they viewed as their adversaries. Pilgrim death was considered tragedy, while Native death was predestined dispossession, fated disappearance, and necessary waste. Bradford described the sight of so many dead Native people killed by disease as “a very sad spectacle to behold,” but it was a spectacle nonetheless. After the “Indian massacre of 1622” left hundreds of settlers dead at the colony of Virginia, such objectification further solidified as conspiracy infiltrated the minds of colonists wary of further Native attacks. At Plymouth, confirmation of those fears came by way of intelligence from Massasoit, a Wampanoag leader and ally to the colonists who warned of the Massachusetts Tribe’s growing resentment. The establishment of an additional settlement adjacent to Plymouth called Wessagusset worsened tensions between Natives and settlers. When news of the attack plot emerged, the settlers decided to strike preemptively. The offensive they proceeded to carry out produced an image that requires our interrogation today.

Myles Standish, an English officer hired by the Plymouth colony as a military advisor, planned and led a group of eight men in a sneak attack on the Massachusetts. Under the auspices of trade, they lured members of the Massachusett tribe into a meeting and murdered them. Afterward, the Pilgrims led by Standish hanged an adolescent and placed the decapitated head of a prominent Neponset warrior named Wituwamat on a pike at the apex of Plymouth settlement, a warning signal to Natives resisting settler encroachment. It remained there for years. Of these events, Bradford wrote:

By the good Providence of God they were taken in their own snare, and their wickedness came upon their own part; we killed seven of the chief of them, and the head of one of them stands still on our fort for a terror unto others.

Months later, when Bradford married a widow named Alice Southworth, they adorned the wedding ceremony with a flag soaked in Wituwamat’s blood. Though these events came well over a century before the invention of the camera, such images of Native death seem like a devious proto-photography. The imagery the Pilgrims created using the bodies of Native people they had slaughtered set a precedent for modern uses of the camera as a weapon. Genocidal impulses drove their exploration of the uses a dead body could serve as a tormenting symbol. The graphic display of Wituwamat’s head and the celebratory use of his blood, while not the first acts of their kind, highlight the colonial objectification of their enemy. Such impulses, manifest in the Pilgrim’s grotesque arrangement of Native corpses, animate devious forms of photography and image-making today.

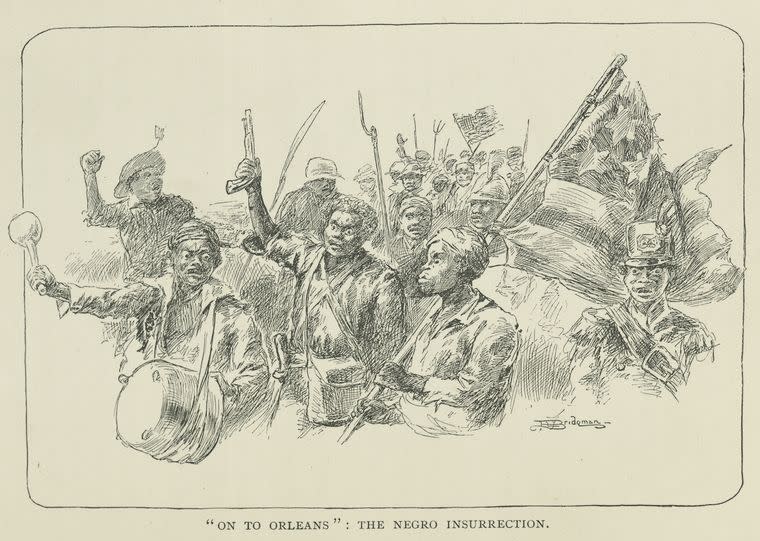

We can observe an egregious echo of this history two centuries later in the German Coast Uprising of 1811, in which hundreds of enslaved Black people in the Territory of Orleans (present-day Louisiana) took up arms and marched from LaPlace, Louisiana, toward New Orleans chanting, “Freedom or death.” Their short-lived insurrection was met by a militia and federal troops, who summarily tried and executed all those rebels they did not kill in battle. In the aftermath of these executions, the rebels’ bodies were mutilated, and their heads were placed on pikes for sixty miles, to warn and frighten would-be rebels from attempting similar acts. As in Wituwamat’s fate, the bodies of the dead rebels were manipulated into a visual message. The white authorities instrumentalized these mutilated bodies, turning the dead into devices for the purpose of counterinsurgent intervention. The naval officer Samuel Hambleton made their motivations even more explicit, saying, “They were brung here for the sake of their Heads, which decorate our Levee, all the way up the coast … They look like crows sitting on long poles.” This arrangement was not simply a careless self-indictment by the oppressor.

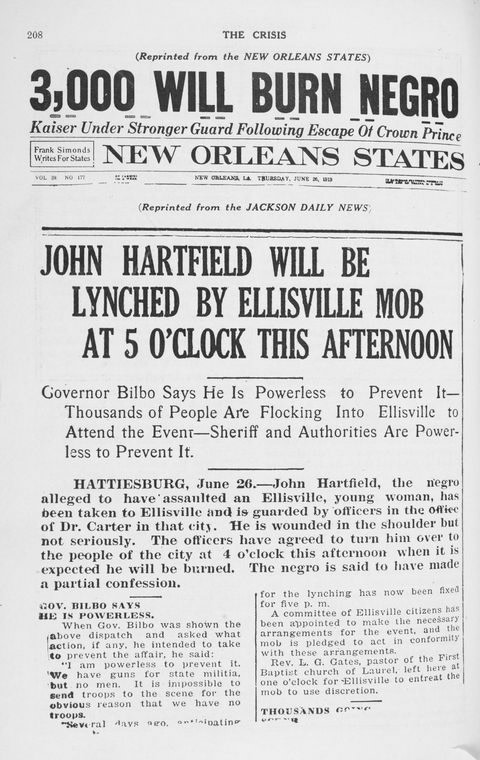

Neither the Wessagusset massacre nor the uprising of 1811 were documented on film, but when the camera arrived, it made possible the same visual project in a new and mass-producible form. Cameras have helped export the ideals of empire, colonialism, and white supremacy and objectified whole peoples, places, and societies. There are countless examples of how this has manifested, but one prominent example from US history is the proliferation of the lynching photograph. While lynchings of Black people became a normalized aspect of US society, so too did their commemoration and dissemination, enabled by the camera. These images were accepted as photojournalism, and the gleeful reveling in these murders led to the popularity of practices such as lynching postcards. Spectators could affirm their participation and interest in a lynching from a distance, even if they had not been able to attend the killing in person. Ida B. Wells wrote of how the practice grew increasingly grotesque, with hangings, burnings, and worse:

Some life must pay the penalty, with all the horrors of the Spanish Inquisition and all the barbarism of the Middle Ages. The world looks on and says it is well.

Not only are two hundred men and women put to death annually, on the average, in this country by mobs, but these lives are taken with the greatest publicity. In many instances the leading citizens aid and abet by their presence when they do not participate, and the leading journals inflame the public mind to the lynching point with scare-head articles and offers of rewards. Whenever a burning is advertised to take place, the railroads run excursions, photographs are taken, and the same jubilee is indulged in that characterized the public hangings of one hundred years ago. There is, however, this difference: in those old days the multitude that stood by was permitted only to guy or jeer. The nineteenth century lynching mob cuts off ears, toes, and fingers, strips off flesh, and distributes portions of the body as souvenirs among the crowd.

As I have written previously, lynching photos can be read as proto-viral content. Participants in lynching and the circulation of its imagery went beyond the mutilations of Native people or of the German Coast rebels by not only keeping pieces of lynched bodies as trophies but also sharing images of the killings as mementos. They did not have social media at their disposal, but bloodthirsty white mobs, settlers, and deputized vigilantes used the camera to extend the life of the violence they committed. The future could now hold picturesque reproductions of their atrocities, much like many of the grotesque posts we see white supremacists sharing and reveling in today. The realities of publicized police killings, genocide, and war have made this more than apparent in several ways. What we see, and how regularly we see it, determines to a large extent what types of violence and victimization get normalized.

This insight explains in part why former powers like Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union nationalized film production as a geopolitical strategy and weapon of war. National cinema is a propagandistic accessory that can legitimize nation-states and reinforce acceptable brutalities domestically or internationally. Characterizing particular subjects or populations as especially disposable with illustrations reinforces discriminatory classifications and further normalizes brutality against those people. Telling in this regard is the fact that the first film to be screened at the White House was The Birth of a Nation, D. W. Griffith’s 1915 blockbuster propaganda. The film, adapted from a racist play wherein theatric visuals of vilified Black people rouse audiences to lynch law, glorifies the Ku Klux Klan as heroes. Photography, in this instance, made anti-Black violence more apportionable; for all its technological advancement, the camera also carried forward the broader oppressive agenda of ruling classes by representing and reproducing the repression of marginalized people. While it opened up a new visual world to people everywhere, the camera has also helped capture and fortify some of the most violent and tragic historical events. This potential is not completely one sided; oppressed people and resistance movements can make counter-propaganda and use the camera to show images of themselves that subvert dominant narratives. To do so, however, requires important understanding of the methods used to make the oppressed permanent objects frozen in our subjugation.

Our awareness of the images we consume and disseminate should be shaped by a political understanding of power. Cameras are subject to the whims and eccentricities of those holding them, and images have long been manipulated. Whether a photojournalist on assignment is directed to seek out particular shots in a conflict zone, or dead bodies are misrepresented as victims or perpetrators, all photography is subject to misappropriation. Propaganda illustrates the expectations and anticipations of a biased audience; it can also shock or surprise people into taking a position they did not previously hold. It is important to be aware that the motivations of the photographer influence what we read in the image of a highly politicized tragedy. The camera, supposedly the ultimate mirror of reality, can nonetheless be directed to only show whichever part of reality its user will permit the viewer to witness. If a photographer, filmmaker, or person circulating a particular image wants the mirror to reflect your status as an object, victim, villain, or otherwise, they can reinforce that categorization by doing so.

Social media maximally amplifies these predicaments. The “timeline” has the potential to become an endless stream of images of death and destruction. Recordings of police brutality become sharable content in the spirit of “exposing” a problem that’s nakedly out in the open. White liberals perversely tell Black people not to look away from crises that have long afflicted our lives. As I have argued previously, these trends reveal a gross misconception that we must visualize oppression and harm to make them believable. After all, many of us who live in the margins of society know there is no victimhood perfect or picturesque enough to make our injuries and deaths believable or unjustified. The carousel of images of our demise shared, streamed, memed, and manufactured online is not a neutral display. Intentionality determines the curation of these images and the categories that shape how they are read. Just as the biases and discriminations of the programmer structures technologies marketed as artificial intelligence, what makes it through to us on Meta, X (formerly Twitter), and other social media platforms reflects trends of thought in society at large.

In February 2024, the Israeli army (IDF) admitted that its soldiers were curating a psychological warfare channel on Telegram called “72 Virgins—Uncensored” that it had created in October 2023. The channel was operated by members of the IDF’s Influencing Department, which usually targets foreign and enemy audiences. The Jerusalem Post reported that the channel’s administrators encouraged followers to share the content “so ‘everyone can see we’re screwing them.’ ” This revelation makes it clear that this type of sharing is a tactic to encourage and normalize the atrocities being carried out by Israel against Palestinians under siege. As in the aforementioned historical examples, using images to highlight the gruesome and merciless power of an oppressor does not necessarily generate sympathy for the oppressed; it can be a tool to reinforce the ruling order. The idea that “seeing is believing” often obfuscates the fact that seeing is the point. It’s often how an oppressive regime, controlling what we see, says, “Do not dare resist.” In order to break through the wall of dead bodies on which hegemony is built, we have to do more than just witness, share, and say that what we see is evil.

The social media timeline’s power to normalize images of genocide, police killings, abuse, and more may seem exceptional, but our society is casually filled with similar visuals. Slave owners, imperialists, and presidents who exterminated Indigenous nations have been turned into monuments. A state forest in Massachusetts bears Myles Standish’s name; Boston University students have protested to remove it from a residence hall on campus. Even works of art that claim to trouble the representation of brutality can reproduce it. In a piece commissioned by the Whitney Museum, sixty-three ceramic heads meant to memorialize the 1811 slave revolt were mounted on steel rods and installed at the Whitney Plantation in Wallace, Louisiana. Lynching photos appear regularly in exhibitions and history books. Curated by the state in its institutions and recalled as important history, colonization comes back to us. So long as Western hegemony and the white supremacist nature of US society remain intact, so too can the oppressive intent behind the imagery. It’s imperative to remember as much when we share visuals of violence in hopes of undermining the dominant mode of how these visuals are interpreted.

It is impossible to take images of the tortured bodies of abused detainees, the stolen remains of Indigenous peoples, and the bullet-ridden bodies of Black people killed by police and show them in a context wholly divorced from the conditions that produced those outcomes. The world that consumes these images is the same one that conditions their possibility. Desensitization can set in even alongside dissent. Witnessing atrocity can become a passive activist hobby or a frozen observance. It can also become an act of flagellantism for those overwhelmed with guilt as well as those who perceive themselves as powerless to enact change. This ritualistic self-traumatization labeled as “care” and “concern” is not liberatory. If seeing ourselves dead and destroyed had the power to liberate, we would have been free a long time ago. It’s not that we should never be able to look; it’s that our looking has to see and surmount the intention behind the image.

1. “A relation of the troubles which have hapned in New-England by reason of the Indians there from the year 1614 to the year 1675 wherein the frequent conspiracys of the Indians to cutt off the English, and the wonderfull providence of God in disappointing their devices is declared: together with an historical discourse concerning the prevalency of prayer shewing that New Englands late deliverance from the rage of the heathen is an eminent answer of prayer / by Increase Mather.” In the digital collection Early English Books Online, vol. 2, University of Michigan Library Digital Collections.