In April 2023, when war broke out in Sudan between the Rapid Support Forces and the Sudanese Armed Forces, twenty-one-year-old Omnia Mustafa had recently graduated with an undergrad degree in international relations and diplomatic studies. We discuss their experience of race and racialization as an African Arab person from northern Sudan, and the atrocities being committed against the people of Darfur and western Sudan. As of this publication, they currently still reside in Sudan but are working toward escaping with their family.

Khadijah Abdurahman: People often split Sudan into a simple binary of Black and Arab, or northern Muslims and southern (as in South Sudan) Christians, without giving further thought or recognition to Black Indigenous sacred practices in Islam, Christianity, or in opposition to both—the specific experiences of the Nuba people, or the Fur, the Masalit, and so on. Where do you locate yourself within the social and political geography of Sudan? How has the war transformed or reinforced your perspective on this?

Omnia Mustafa: My father is from central Sudan, Algezeira state. He is from a tribe called Jaali. My mom is from a tribe called Shaigy, and they’re notoriously known as Arabized Nubian tribes. So I would identify myself with being a northern Sudani who’s Muslim and has Arabic culture. I think, as Sudanese people, we always have this issue with identity as we look Black, but we speak Arabic and we share the same culture as Middle Easterners and the MENA [Middle East and North Africa] in general. When we are engaging with African people, they tell us, “You’re too Arab for us.” And when we engage with Arab people, they tell us, “You’re too African for us.” So we never fit in or identified ourselves with any of those identities. None of them felt true to ourselves. After thinking a lot, I’ve just come to the conclusion that I identify as an African Arab person. By “Arab,” I don’t mean sharing Arab ancestry. I just mean it as part of my culture, the same way Hispanic people are Hispanic because they speak Spanish. I’m Arab because I speak Arabic, and that’s it—not because I look Arab or I am from the Arab region.

Honestly, the war in Sudan has been a very informative era for me. I got to hear and see a lot of things from the marginalized groups, like those from the Nuba Mountains and South Sudan. I would say before this war, we were living in ignorant bliss, like many privileged people around the world. We did not acknowledge how privileged we were compared to the marginalized groups in my country. Because I studied international relations and politics, I did have a vague idea of what those groups go through, but that was just theoretical studies, not actual experiences. We northern Sudani, and people who grew up in Khartoum, never have those uncomfortable conversations. The war has started a space for us to hear and see how oppressed and marginalized groups in Sudan are feeling, what they’re going through, and how, even in times of war, they are even more marginalized and even more oppressed by us.

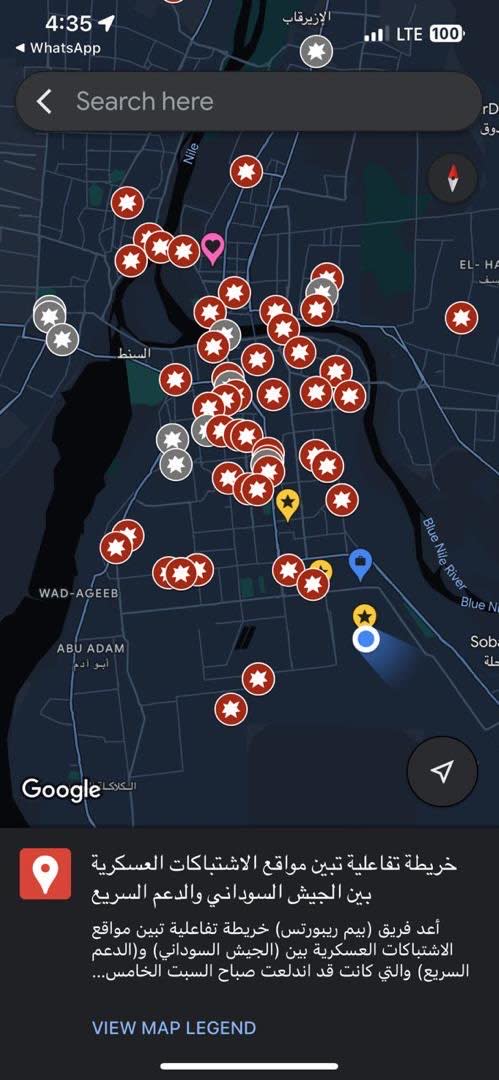

Right now, the only untouched places in Sudan are the east and north of Sudan. Meanwhile, central and western and southern Sudan are mostly raging conflict zones. Even if back in the day people were brainwashed by government propaganda that “those people are rebels and we’re putting down rebels”—like, “we’re not doing anything else, we’re not violating human rights or international law or anything, we just have rebels that rose from nowhere for no reason and we’re putting them down”—now, you can see it clearly. You see the injustice and the oppression unfold before you. Even online, the discourse has changed. Now, we talk more about it. We listen more, and we’re more open minded. Honestly, I’m heartbroken that it took us—personally, it took me a whole war—to see what they are going through. It makes me feel very guilty, and just like not a very good human. But it took me so long to acknowledge and be more well versed and knowledgeable of what the western Sudanese people are going through.

Khadijah: Due to the legacy of the Save Darfur movement, the Western public easily identifies the Rapid Support Forces as the villain because they grew out of the Janjaweed militia. Like much of continental African politics, there’s a way that images of the Janjaweed rampaging Darfur are understood as a “humanitarian crisis” outside of politics, or at most “an ethnic conflict.” Nonetheless, it is relatively easy for the West to understand that RSF is the “bad guy.” On the other hand, many marginalized communities from outside of Khartoum also raise that they’re equally terrified of the SAF. What is your experience and perception of the Sudanese Armed Forces?

Omnia: This is a bit of a risky question, but I’m going to answer the best I can. The RSF is whitewashing the Sudanese Armed Forces’ history. How can the RSF be the only bad people and the SAF the heroes if the RSF was formed and trained by the Sudanese Armed Forces, and working hand in hand up until this war? They cooperated with each other on the crimes and the genocides that happened in Darfur, even before the formation of the RSF [when the Janjaweed, its antecedent, was already active], since 2003. The Sudanese Armed Forces were carrying out those atrocities in Darfur, so I don’t think they are heroic.

I think most of the Sudanese people understand that now. They just support the Sudanese Armed Forces because they are the only legitimate authority right now. And to say that they are two sides of the same coin would give the RSF more legitimacy than they should have; because at the end of the day, they are a rebel faction of the Sudanese Armed Forces and a tribal militia. It doesn’t make sense to call this conflict two sided, two equal sides having a fight.

I witnessed the 2018 December Revolution in Sudan, and have seen firsthand the brutality that was used against us young protesters; I was fifteen, sixteen at that time. I’ve lost many young friends who were sixteen and seventeen due to this brutality. I have also very close friends who’ve lost limbs and are now disabled because of the brutality they have faced for protesting the past regime and wanting a better Sudan. People get tired after living for thirty years under dictatorship and an oppressive, genocidal system. So, yes, I wouldn’t say I’m very fond of the Sudanese Armed Forces, but I would be a total liar to say that they don’t have support, my support, in this war; because right now, to be safe, I’m literally in an SAF–controlled area. My only thought of how this war would end is by them winning. Then I could envision a future for Sudan. Because we will get to call for a reform. We can bring down the leadership. We can prosecute them. We can do all that.

But if a paramilitary, ethnic tribal, genocidal militia wins, I don’t know how you’re going to envision a future for a country, especially one that has systematically targeted its educational institutions, healthcare sectors, and the infrastructure of Sudan. What the RSF have been doing, and are still doing, is destroying the identity of Sudan and destroying anything that makes Sudan Sudan. They’re setting us centuries back. I would not see any future with those people, especially because they are very, very, immoral, and their whole fighting agenda—I don’t know how to put this in words, but it includes looting and raping and killing. I don’t see any future for Sudan with the RSF in it.

Khadijah: What do you have to say to people who ask why the genocide and war in Sudan isn’t as documented or as visible as Gaza?

Omnia: First of all, Sudan is much, much bigger. Gaza is a small strip with 2 million people, so it’s easier to document atrocities there than Sudan. Number two, the telecom blackouts: in Gaza eSIM cards work, but in Sudan they don’t.

Number three, the targeting of activists and Sudani and journalists, by both the RSF and SAF, makes it very, very dangerous to speak up in Sudan right now. I am personally endangering myself by building a platform online and advocating for Sudan. Many senior journalists and activists have reached out to me privately, saying to lay low as much as I can and not share much information online. A lot of people advise me to be as discreet and anonymous as I can. But eventually things got out, with the amount of interviews and things I’ve done. Eventually I started to see my information out there. Now, I’m the most scared because the RSF are still threatening to invade where I am. At the same time, a lot of their supporters have been harassing me online. So now I know that they know I exist. My most reoccurring nightmare is to be captured by them and tortured for being vocal online. This part, specifically, scares a lot of people and makes them shy away from documenting or talking about Sudan.

Number four is the looting. Let’s say, if you are in an area where the RSF are and you’re trying to document what they’re doing, there is a high chance that you might get a bullet through your forehead. And there’s an even higher chance that you wouldn’t even have your phone to document that, because there’s a high chance that they would have already looted it. They loot at checkpoints. They come to houses. They loot you at your house. They loot you in the street, everywhere. It’s very hard to keep your personal belongings when the RSF are present. So the people who are there don’t really have phones. They don’t have connection. They will literally get killed for filming and documenting. So how do you expect to get footage? Most of the footage we get of RSF violations comes from them. It’s from themselves. I still don’t know why they do that, but they film themselves committing atrocities.

They filmed themselves committing acts of genocide and ethnic cleansing in Darfur recently. There was this video where they lined up a group of boys; they shot them and they buried them alive. They also filmed themselves raping women. They’ve filmed themselves killing the governor of a state in Darfur, and they filmed themselves playing with and disrespecting his body. It’s crazy when you think about it. They also filmed themselves unlawfully detaining, imprisoning people and starving them.

Khadijah: How do you charge your phone, or remain online, during frequent telecom blackouts?

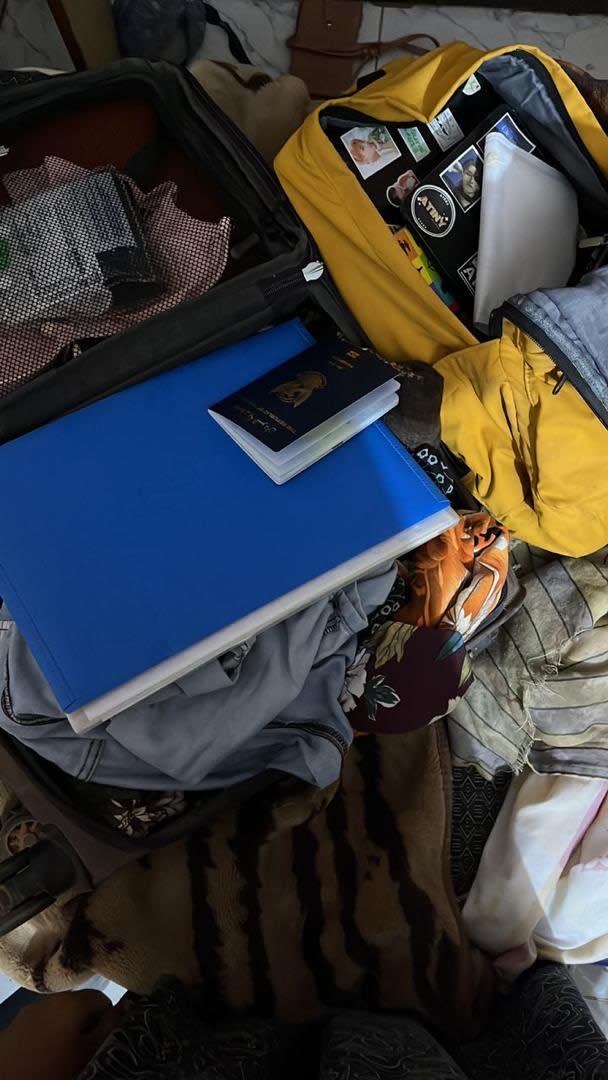

Omnia: In the first months of war, the situation was much, much worse, when I was in the city of Medani—before my second displacement. There was no water or electricity at all because the huge influx of internally displaced people that came to the city basically dampened down its infrastructure. It was not made to sustain that amount of people. There was a lot of water shortage. I think for four months we didn’t have water. And the electricity would go off for fifteen to nineteen hours a day. It was very hard for me to stay online or charge my phone, and at some points we would literally not have water to drink. We would stay thirsty all night and not be able to go to the bathroom due to these things. But after about six months, it was much better. When the war expanded in the city I was in and we had to flee to a village, I wasn’t able to charge my phone at all. I would be offline for a couple of days, without any internet connection at all. But I was able to get out of there and go east, to another state. Even there, the electricity would go off for eleven to twelve hours, and I would find it very hard to charge my phone. So I’d just wait for it to come back—if it ever comes back. There were also telecom blackouts when I was in that state. I came to where I am now when it was still winter. During winter, there are not much electricity blackouts. There are still blackouts, but it’s still more stable than it used to be back in the day.

Khadijah: What does routine look like within the confines of war?

Omnia: Honestly, my routine has shifted so much. It’s drastic. Before the war, I had just graduated. I was interning, planning to do my master’s, and had a very, very active lifestyle. I was always doing something. But since war, obviously I’m now unemployed, and there’s nothing to do. My days are void and empty and very unproductive. There’s nothing to do, honestly. I just wake up, go to sleep, wake up, go to sleep. That’s it. I have tried to do things like reading. I do read a lot. I read so much. In 2024 alone, I’ve read almost thirty books so far. I’m trying to learn a new language. I’m trying to work out. But honestly, there is nothing to do, and there is the mental fatigue and depression because of the war and the drastic change of how our lives used to be to what it is like now.