1

In the beginning, there was the nursery, one of the characters in one of Virginia Woolf’s novels remembers, with windows opening on to a garden, and beyond that the sea. It’s a fun rejoinder to millennia of male chauvinist origin stories about the Word, Father, Son, Holy etc. But that character was lucky. In today’s housing market, how many newborns can afford a room of their own? Forget about one with ocean views.

There were predictions, early in the pandemic, that as offices closed and white-collar professionals shifted to working from home, rents in San Francisco and New York would fall. On Instagram, millennial influencers were going off the grid. On Twitter, a new generation of culture warriors bravely admitted that they were sick of pronouns, and unhoused people, and moved to Austin. Keith Rabois kept tweeting about what a cool time he and all of his cool friends were having in Miami.

Even we developed a habit of scrolling at night through Zillow listings in the countryside, if only to avoid reading about the growing numbers of the sick and the dead right before trying to sleep.

But in fact, the predictions did not come true. Rent is increasing at its fastest rate since 1986. If you want to rent, be prepared to pay a broker 15 percent to advise you on how to bid your own rent up. If you want to buy, good luck. Rising interest rates should cool the market soon. But for now, they mean that, even for those with good credit scores, mortgage rates have nearly doubled since 2020.

While we were writing that paragraph, we got a New York Times push notification informing us that the housing shortage is not just a coastal crisis. Boise, Idaho is short at least 13,000 units. Here comes another: Shelters across the US are reporting a surge in people looking for help, with wait lists doubling or tripling in recent months.

It’s getting harder and harder to get in on the ground floor of Maslow’s pyramid. Citizens struggle to find shelter, from sea to shining sea.

2

But you knew that. About moving to Austin: As we were editing this issue, approximately half of all people in the United States officially lost a right that residents of many states had already lost in practice.

We knew this news was coming. Still, it felt crushing. Watching Nancy Pelosi recite poems, and Joseph Biden and Kamala Harris stammer in response to questions they have had months to prepare for, it is hard to know whether to scream, or to scream.

We cannot talk about the theme of this issue without talking about the Dobbs ruling. If for decades the right to an abortion was grounded in the right to privacy, for better and worse the right to privacy has deep ties to home, in the sense of private property.

The idea that a person has the right to keep what happens behind closed doors behind those doors offers important freedoms. The ability to control who gets to know what about you is a crucial precondition of being free to do what you like. Privacy, in the sense of secrecy, preserves personal autonomy. Domestic life has been a central site of aspiration and emancipation for countless people who do not, or cannot, find freedom in public spaces. For many, home offers a refuge from racism and homophobia. It affords the ordinary pleasures of intimacy.

At the same time, however, the powerful have often invoked privacy to conceal their abuses of power. In Ancient Rome, the ideal of all political authority (auctoritas) was the rule that the man of a house exercised over his wife, children, and slaves. In the United States, too, the history of the right to privacy remains inseparable from the history of men treating women and children who depend on them—and white people treating Black people—with impunity.

Generations of advocates and activists have argued that it was a mistake to ground abortion rights in privacy rights. Recent events prove, as if proof were still needed, that the move that seemed strategic in the early 1970s was not in fact strategic. It made abortion rights fragile.

If the right to privacy has historically been grounded in the right of the man of the house to do what he wants there, people who get pregnant do not get to go home. We are home.

So, as we face the prospect of even more people losing even more—rights to contraception, marriage, and even interstate travel—we have to be prepared to do at least two things at once. We have to build, and connect, spaces of care shielded from prying eyes. And we have to strive for a world where ownership of private space does not decide so much.

3

What’s tech got to do with it? Everything. And not only because Airbnb rentals and Zillow’s investment arm are helping drive a housing crisis, sending more and more people to the streets. Not only because, as one tweet we saw lamented, millennials forced to move back in with parents are now Zooming with their therapists like someone reporting LIVE from the scene of the accident!

Anti-choice groups have long used targeted ads to direct misinformation to women searching online for abortion services. Now, for peanuts, brokers sell highly sensitive data about the geolocation of patients to would-be vigilantes. But the ways that technology shapes the ever-shifting divide between public and private—your business and your boss’s, or the state’s—run even deeper.

Home is, and has always been, entwined with technologies. Indeed, evolutionary scientists and archaeologists recognize dwellings themselves as technologies, among the tools that make humans human. Our homes enclose and arrange us. They shape our relations and communications, and their traces, in particular ways.

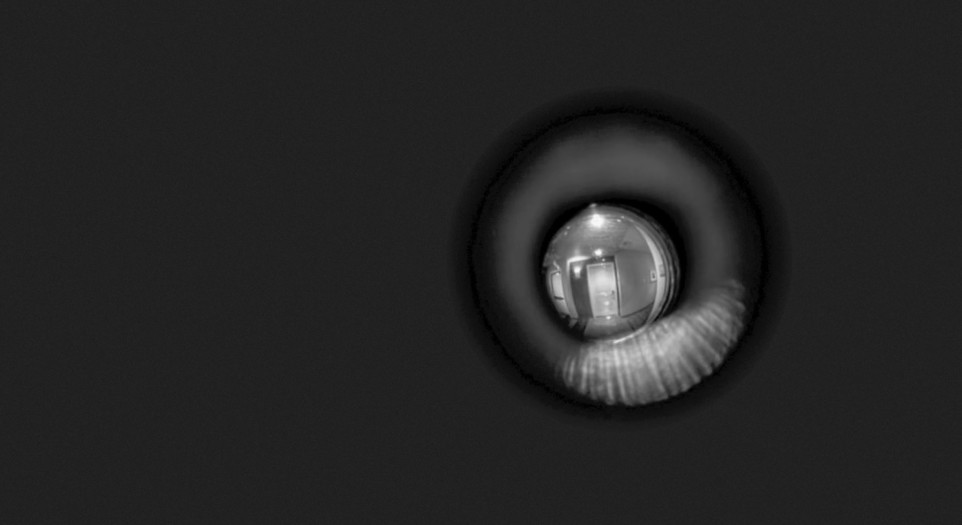

This means that the growing number of technologies that market themselves by claiming to protect the home are in fact transforming the boundaries that define it.

Life360, a smartphone app that tens of millions of parents use to track their children in real time, has been caught selling personally identifiable information about those children’s whereabouts to brokers who will sell it to almost anyone.

Amazon and competitors like Wyze have developed smart cameras that they encourage families to use to monitor their stoops—and other people’s—to keep an eye on Amazon delivery workers and anyone else who happens by. Other smart cameras reassure parents that they can leave their kids while keeping their nannies, and other household workers, under continuous surveillance.

Promising to preserve the sanctity of the private sphere, at the same time, these devices mine the private sphere for content that they disperse to the cloud, to leaky servers from northern Virginia to southern Guizhou.

4

This issue approaches the shifting intersections of home and technologies without making assumptions—and with an eye to justice.

In one piece, a public school teacher explores how, during the pandemic, edtech firms have garnished millions from public emergency relief funds without delivering on their promise to provide equal access to education. How could they? Students’ living conditions shape their learning conditions, even once quarantines are over.

In another piece, researchers look at how one person’s home becomes another person’s workplace, and still another’s data quarry. Care platforms incentivize parents to cooperate with their data gathering by surveilling caregivers, while making the caregivers more precarious.

In this issue we see the sins of the father continuing to be visited, if not on the son, then on other people’s children. Our authors explore how new systems replicate old inequalities. In South Africa, automated credit rating systems built on decades of racist data re-segregate cities; despite formal equality, algorithmic apartheid succeeds apartheid. In the United States, Black families are subjected to obscene levels of surveillance and violence, not only from the state but from private agencies to which the state has delegated its coercive power. Under these circumstances, our author recounts, having a neat house when the family police show up in the middle of the night can be the difference between keeping your children and having your family destroyed.

Here, and elsewhere, we also glimpse homes as sites of creativity and resilience. Right now, TikTok influencers are making art, or at least satire, out of homes that Zillow makes into content, to entertain members of a generation that is struggling to afford housing. Garment workers moving between villages in China’s Zhejiang Province and Prato, Italy are finding opportunity and resilience in family networks, if also exploitation. So, presumably, will the migrants who succeed them make new kin.

Google Nest and its imitators would have us believe that we can remain kings of our castle, and everyone in it, even when we are away. By contrast, we share the view of the philosopher who said that it is part of morality not to be at home in one’s home. You can take us out of our home, but not our home out of us, and for those who are lucky, home may be a site of nostalgia, even if you can never go home again.