In the first days after I found out I was pregnant, my number one pleasure was tracking my embryo’s growth on various apps. As nausea set in, my morning ritual consisted of crunching Cheerios in bed while clocking the latest developments: one week the apps told me my baby was the size of a poppy seed, the next week a pea. When only my inner circle knew that I was knocked up, these apps acted as chatty confidantes. Their girlfriendy tone assured me that everything was moving along fine.

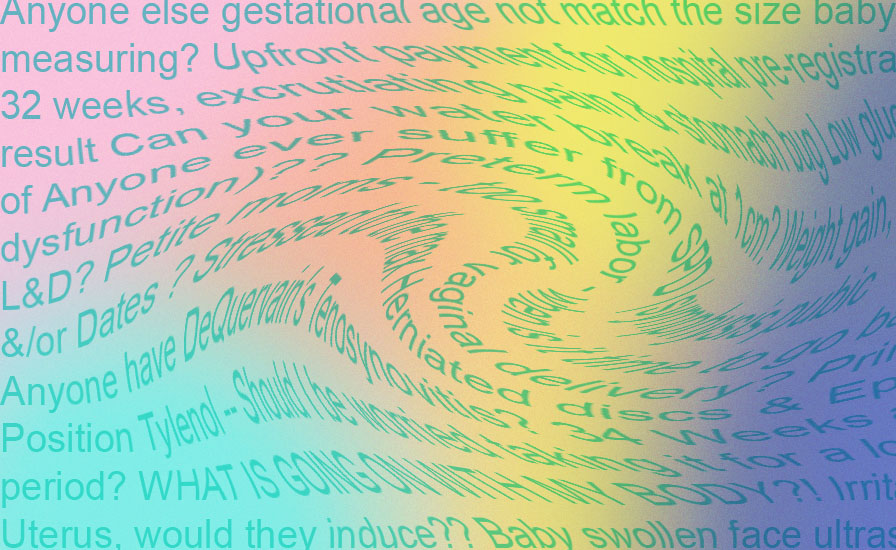

If I scrolled far enough or swiped the wrong way, I would occasionally land on the “community” sections of these apps. A typical series of posts might look something like this:

Light spotting at 12 wks normal?

Nub & Skull Theory

BFP or BFN? Thoughts?

Constipation!

12 Weeks and Couldn’t Hear the Heartbeat — But all is OK!

**Update 7dpo test** Who else just started their TWW… 3 DPO here

Veiny boobs LOL

Early miscarriage, cervix feels weird

Lord help me

Most of the time, I would click away. I was mystified by the acronyms and uncomfortable gawking at their naked vulnerability. On the one hand, I felt for these women, who clearly had nowhere else to take their fears, frustrations, and disappointment. On the other hand, I was trying to enjoy my BFP (Big Fat Positive) in peace. I found that these conversations were more likely to inspire new anxieties than to assuage the ones I already had.

I got my first exposure to such “communities” through pregnancy tracking apps like Glow. But when I did Google searches for things like “round ligament pain” or “morning sickness when will it end,” I discovered another place where people were discussing pregnancy online: website forums that look like relics of the AOL era. I couldn’t fathom why anyone would spend their time poring over the comments on these sites, let alone posting them. But millions of women do, posing (and answering) every conceivable question.

BabyCenter.com claims to be the world’s number one digital parenting resource, reaching 100 million people monthly and attracting eight out of every ten new and expectant moms each month in the US. Since its publication in 1984, the blockbuster pregnancy guide What to Expect When You’re Expecting has done brisk business enlightening and terrifying parents-to-be. Today, the online home of the pregnancy-guide-turned-empire, Whattoexpect.com, has a new community post every three seconds. These sites (and a handful of others) play host to groups as broad as “birth clubs” (comprised of women due the same month) and as narrow as “40+ Expecting 8th LO” (Little One).

Despite the proliferation of slick apps dedicated to fertility and pregnancy, much of the conversation still happens on old-school, web 1.0 forums like BabyCenter and What to Expect. Hectic, disorganized, and largely anonymous, these message boards recall the chatrooms of the 1990s, where you could be anyone and say anything under the cover of a screen name. While plenty of the pregnancy action has made the move to social media — where both “mommy” groups and branded pages abound — the forums maintain the upper hand in one key way. Whereas on Facebook users have to join the group in order to see the conversations, traditional message boards are far more lurkable. “Many studies show that there are way more lurkers than posters,” says Anna Wexler, a bioethics fellow at the University of Pennsylvania studying the rise of do-it-yourself medicine. “If you look at the number of posts on these forums, the number is tremendous — on some of the What to Expect ‘birth clubs,’ it’s over 500,000 posts already.”

I stopped finding the forums so pitiable as soon as I got my first bad test result. When I was around ten weeks pregnant, I went in for a routine test called a nuchal translucency. Analog and old-school, the ultrasound scan measured the fluid behind the fetus’s neck to look for Down syndrome, which previous tests had indicated the baby did not have. It didn’t even occur to me to be nervous about this test, so I didn’t pay attention to the Very Bad Sign of the ultrasound tech quietly turning the monitor away from me.

I waltzed into my midwife’s office, ready to learn about breathing techniques and placenta smoothies. Instead she gently explained that the baby seemed to have excess fluid behind her neck — we learned it was a her — and that it could mean a few different things, none of them good. I was so shocked and distraught that I lost the ability to hear and process information. As soon as I got home, I descended into a Google vortex, which led to countless conflicting perspectives across multiple message boards.

Down the Rabbit Hole

Once I was referred to a Maternal-Fetal Medicine practice to run more tests, I quickly understood the primary reason women take to the boards: getting a hold of a doctor is too annoying and takes too long. “If you have a question and you don’t want to wait until your doctor’s appointment and don’t want to make the call, the forums are just really immediate,” explains Wexler. Most ob-gyn offices also employ a firewall of nurses to answer more basic questions and refer the complicated ones to doctors. “I can’t directly contact my fertility doctor,” explains Aba Nduon, a psychiatrist who moderates a pregnancy subreddit. “She has a nursing team that I can email or call with questions and then wait until they’re able to get in touch with her, or you can post on a forum and get a much quicker answer.” Intended or not, the effect is to shame patients into being very selective about what issues they bring up to their medical team.

It turns out another very good reason to hit the forums is to decode the complicated answers (or opaque non-answers) that busy, impatient medical professionals actually do tell you. For every casual aside (“you’ll probably be fine”) or stern command (“stay on bedrest until the bleeding stops”), there’s an online army of amateur experts ready to explain, debunk, reassure, or raise the red flag. As Wexler points out, “Even if you have the most amazing OB in the world, just hearing from your OB that something is normal is not the same as hearing from twenty people who are going through the exact same thing as you that it’s normal and you’re okay and you’ll get through this.”

While the forums may seem like a potential hotbed of misinformation, the volume of voices tends to serve as a check on bad advice. The more science-minded threads offer an unexpectedly effective form of crowdsourcing, providing both quantity — multiple users chiming in with their own experiences — and quality — laypeople who are so deeply immersed in the finer points of fertility treatments or fetal development that they can competently address even the most obscure questions. Nduon told me that she’s also part of a Facebook group for female physicians going through infertility. Compared to the laypeople equivalent, she said it’s “honestly not too dissimilar — we have a lot of the same questions because a lot of this stuff is very specialized information.”

If you question the wisdom of trusting strangers on the internet over your clinical care team, you probably don’t know how perilous a condition pregnancy in America is. The United States is the most dangerous place in the developed world to deliver a baby, with 26.4 maternal deaths per 100,000 births as compared to fewer than ten in Germany, England, France, Japan, and Canada. The US is one of just thirteen countries globally where the rate of maternal mortality is worse than it was twenty-five years ago. The CDC reports 700 deaths and more than 50,000 near-deaths annually. If things have gotten worse for women, they’ve gotten disproportionately worse for black women, who face three to four times the risk of pregnancy-related death as compared to white women. Black infants are more than twice as likely to die as white infants — a disparity that’s wider than it was before the Civil War.

According to a USA Today investigation, half of those deaths could be prevented and half of the injuries reduced or eliminated with better care. The life-saving interventions aren’t dependent on cutting-edge technology, but on basic monitoring that’s standardized in the rest of the developed world. Since many US hospitals don’t require widely recommended measures like quantifying blood loss or quickly treating dangerously high blood pressure, doctors and nurses rely on their own intuition rather than best practices. And if you can’t trust your doctors to follow simple rules to keep you alive, why should you take all of their other directives at face value?

Sick of This Shit

When I started bleeding at work a few weeks after the grim test results, I called my ob-gyn’s office in a panic. I got the automated answering system, and pressed 1 for “health care providers and true medical emergencies” with conviction. The man who answered acted as if I had casually mentioned that I was experiencing some cramping and wondered if I might swing by for a consultation. He begrudgingly penciled me in for a 12:30 appointment (it was noon). When I arrived, the receptionist told me to have a seat, like I was waiting for a dental cleaning.

Before any examination, the doctor told me that I might just be passing a clot and be okay, or I might be starting to miscarry, in which case I would just have to let it happen. I was appalled that these radically different outcomes were being offered up as two equally valid prospects. An ultrasound showed the same scene I was used to: fetus squirming around like it was a regular day in the uterus; heartbeat whooshing away. I think the doctor might have actually shrugged when she turned to me and said, “Everything looks fine.”

Unfortunately, this didn’t change her previous statement, meaning that I could still be kicking off a miscarriage. Unbelievably, her prescription was to send me home and see whether it got better or worse. “So just wait and see if I stop bleeding or if I’m having a miscarriage?” I tried to clarify.

“If you’re soaking through more than two pads an hour, call us,” she told me.

In the days that followed, I waited, and watched. I couldn’t manage going to work physically (I was put on bed rest) or emotionally (I was constantly on the verge of tears). I was stuck at home with nothing to do but watch bad TV and occasionally sneak a glance at the various apps, peeking through my fingers like I was watching a horror movie. All of the breezy talk of fruit sizes and organ development quickly started to feel very dark. The apps’ daily tips about iron-rich foods and how to spot the first kicks were bleak reminders of milestones I might not reach. But a hop-skip over on the community section were thousands of women whose fertility experiences deviated significantly from the joyful journey of belly selfies and gender-reveal parties.

For me, dwelling on stories of fetal anomalies and miscarriages felt grim and panicky; reading about other women’s awful experiences made the prospect of an unhappy ending that much more real. I felt like I was jinxing myself — and my baby — by even remotely identifying with them. Still, it was weirdly reassuring knowing that other women were finding some solace while going through the same type of misery. Alongside those happy posters “staying positive” or “waiting for that BFP” was an equal and opposite chorus bemoaning their latest setback or saying they were sick of this shit. The latter group tended to rely less on hope and faith than data and odds, whether dealing with a complication or trying to get pregnant in the first place. While I couldn’t bring myself to join them, this was my tribe: science-minded cynics who still refused to give up.

But I found it technically challenging to lurk effectively, because the communities are so steeped in their own impenetrable lingo. Nduon, the psychiatrist, tells me that the conversations in her pregnancy subreddit can be difficult for outsiders to parse. “It’s very hard to understand what on earth people are talking about if you’re not familiar with the medications or different procedures.” She contends that it’s not just a pregnancy thing, but a human thing: “You create a language whenever you join a new group. You fall into the language that the group uses; it makes you feel like a part of the community.” The lexicon not unites the in-members, but also effectively shields them from intruders.

The amateur scientists who can rattle off their hormone levels and treatment protocols are bound not just by their common language, but by the many ways in which modern medicine has failed them. These women have sought out the top doctors and the soundest science, scouring the research and polling fellow lay-reproductive endocrinologists to maximize their chances of conceiving or giving birth to a healthy baby. But for all the promises of cutting-edge technology, the common denominator for women heading down that road is past disappointment.

When faith in the latest innovation falters, a trustier form of tech is waiting in the wings. And an older form of tech: old-school message boards that promise anonymity rather than the interconnectedness of social media. The web 1.0 setup of these forums is a feature, not a bug: that wild and wooly quality of the early internet makes room for a rare kind of openness and honesty among intimate groups of strangers.

Keeping it Sticky in the Cyber Sweatshop

Long before branded content was a twinkle in any media corporation’s eye, early internet companies recognized the value of building communities that produced the “‘stickiness’ that maintains users’ attention and increases the emotional cost of shifting sites,” in the words of feminist theorist Kyle Jarrett. According to a 1999 Wired article, AOL deployed (not employed) tens of thousands of “community leaders” to keep its chat rooms and message boards humming, compensating them in the form of free AOL memberships and select online perks — that is, until a group of them brought a class-action lawsuit against AOL’s “cyber sweatshop.”

Two decades later, women are still providing the same free labor, keeping the leading pregnancy sites nice and sticky. If they feel like a vestige of the past, it’s likely because there’s not a lot of incentive for their owners to update them. “They’re still getting a ton of content, and that content is coming up in searches on Google, so as it is it’s probably drawing a lot of traffic without them having to invest anything,” Wexler, the bioethics fellow, explains.

When I reached out to one such site, The Bump, to find out more about its community, a representative was keen to steer me toward their social media content instead. She explained that while their forums “originally served our users by fostering a sense of community for new and expectant parents,” they have “taken note of the shift away from forums and towards social media” and shifted their own attention accordingly. I had a hard time squaring this supposed migration with the numbers: The Bump’s Facebook page has fewer than 300,000 followers, while over at the message boards, the “Trying To Get Pregnant” section alone has 223,500 discussions and nearly three million comments. A single thread titled “what does a positive pregnancy test really look like??” has over 500,000 views.

A quick scroll through The Bump’s Facebook feed may help explain why. It shows plenty of upbeat material and clickbait-y headlines, with the occasional frazzled mom or baby with spaghetti on his head as the only nod to the tougher side of pregnancy and motherhood. But if you’re panicking over bad test results or low hormone levels, the knowledge, support, and advice of like-minded women is a lot more useful — and comforting — than a funny #momfail. As I faced down the prospect of a terrifying diagnosis or miscarrying altogether, the sanctioned kinds of “problems” discussed in the official content on sites like The Bump — morning sickness, body image issues, and worst of all, “baby brain” — began to enrage me more and more. It was as if the worst thing that could happen to you was throwing up at your desk.

The social channels of all the major pregnancy players are also peppered with paid partnerships — tie-ins with eczema creams and baby food and diapers. It’s no wonder that The Bump and its ilk would prefer we spend our time browsing monetized social content rather than reading the forums for free. It’s hard not to conclude that the more sanitized version of pregnancy has become more lucrative, while the messier version remains more popular. Despite companies’ best efforts to mold the communities they want, women continue to carve out the communities they need. As long as the pregnancy narratives in mainstream culture stay relentlessly positive, women will go underground to find (authentic) stories and experiences that actually reflect their own.

The fact that women have to go underground to find these narratives is partly a function of how much the experience of pregnancy has changed. In her book Ina May’s Guide to Childbirth, renowned midwife Ina May Gaskin describes the “techno-medical” model of maternity care as a “male-derived framework” built on the assumption that “the human body is a machine and that the female body in particular is a machine full of shortcomings and defects.” In this framework, which unsurprisingly arose alongside the Industrial Revolution, doctors are the ultimate authority, while the responsibility for any failure to progress in pregnancy or labor is placed squarely on women’s shoulders.

Before the techno-medical model of maternity care took hold, these communities existed IRL: midwives, mothers, and sisters formed a core support group for pregnant women. As Richard W. Wertz and Dorothy C. Wertz point out in Lying In: A History of Childbirth in America, childbirth in the United States was seen as a social experience through the nineteenth century — an opportunity for women to express their love and care. While there are plenty of reasons not to glorify those days, this approach had its upsides.

According to Gaskin, before the new model of birth had fully taken hold, nineteenth-century (male) doctors recognized the importance of staying out of a laboring woman’s bedroom until “women helpers” determined it was time to assist. As long as labor stayed in the home — where doctors couldn’t shoo away persistent women helpers — labor stayed social. In the humanistic (read: woman-centered) model that once reigned supreme, monitoring the physical, psychological, and social well-being of the mother-to-be was considered as important as minimizing technological interventions. But once the business of birth transitioned to the hospital setting, men and machines took over. While midwifery continues to gain traction in the US, the masculinized/medicalized approach remains dominant. Absent women helpers to do battle for us in the delivery room, we turn to the internet for the social experience we still crave.

Unruly Forums for Unruly Bodies

I was pregnant, and then I wasn’t. There was before, and there was after. After, I operated in a constant state of dread. I dreaded anyone asking me about it and I dreaded having to explain myself. Not because I was sad (I was) or ashamed (I wasn’t) but because I didn’t want to do the emotional work of managing their discomfort. Faced with unnerving news that they’re ill-equipped to respond to, most people will just say they’re sorry. But this puts the suffering person in the uncanny position of comforting the un-suffering person, reassuring him or her that everything is fine, which of course is a lie designed to end the conversation. Every interaction continues to remind you that it’s easier to keep your feelings to yourself than to apologize for other people’s unease.

Supposedly we live in a society where we can talk about anything. Technology has ended privacy; everything (and everyone) is fair game. Tabloids scrutinize celebrities for the faintest hint of a “baby bump” and announce every confirmed pregnancy with great fanfare. But we’re not equipped to handle the cognitive dissonance of a pregnancy gone wrong, or a failure to conceive in the first place. As Jen Tye, COO of Glow, puts it, “Sometimes I think the uncertainties that come along with being pregnant — the questions, the worries — some of the concerns may be harder to share because there’s this idealized view of what pregnancy is. You’re just supposed to be glowing and happy and that’s it, but it’s not.” Even the most well-meaning, genuinely caring friends and family struggle to navigate tales of fertility woe.

In the US, most of the pregnancy literature says to wait until the second trimester to announce your pregnancy. Most of my friends who’ve been pregnant seemed to respect this rule of thumb, and it has the standardized feel of medical truth. Even those most notorious oversharers, the Kardashians, have gone to great lengths to keep their pregnancies under wraps for as long as they could. But when you read between the lines, there’s no concrete reason to wait that long other than that, if you’ve made it that far with a clean bill of health, the risk of birth defects and miscarriage drops to almost zero. Which sounds reasonable, until you realize that traditional wisdom dictates that you shouldn’t tell anyone about your pregnancy until you know a (healthy) baby is definitely coming out the other end of it. The unspoken part of the second trimester “rule” is: keep your miscarriage or abortion secret. This effectively enforces a code of silence about an already-isolating experience.

As anyone who’s experienced pregnancy loss quickly discovers, it’s an incredibly common phenomenon: 10-20 percent of known pregnancies end in miscarriage, and at current rates almost a quarter of American women will have had an abortion by the age of forty-five. So, so many women told me about their own experiences when they found out what I was going through — women my age who worked in the next cubicle, or women my mother’s age who had raised my best friends. Some I had even known when they were going through it, and I never had an inkling. And in all cases, I wouldn’t have heard their stories if I hadn’t volunteered my own. These points of connection were some of the few shreds of solidarity I felt during the most alienating periods of my life.

The problem is that since people rarely talk about pregnancy loss, the act of conveying a matter-of-fact life occurrence — I was pregnant, now I’m not — takes on the ick of an overshare, reinforcing the pressure to keep quiet. If you’re lucky, close friends and family will rally around you. But more likely than not, acquaintances and colleagues will be discomfited by a revelation about something that happened inside your body. Given the choice, they would probably prefer not to know, and be left to privately wonder why you never ended up giving birth.

This extreme discomfort with any deviation from an idealized version of pregnancy — let alone any discussion of it — is what forces women underground, to unruly forums for unruly bodies. When the bodily machine malfunctions and all of the short circuits are exposed, the infrastructure of the internet forms a protective shield. On the forums, you’re only as visible as you want to be: they provide cover in the form of a username disconnected from the rest of your social media presence; a persona without a personal brand.

Suddenly, internet strangers start to look a lot more appealing. You don’t have to explain yourself, and no one says I’m sorry. And if anyone feels uncomfortable, they can show themselves the virtual door.