Your project is called the Glia Project. Does the name mean anything?

No. It just sounded medical and we all liked it. One of the engineers was like, “Glia… I like Glia.” Okay, great. We didn’t really care about a name, but we needed one to apply for a medical license and The High-Quality, Low-Cost Open Access Medical Device Project just didn’t seem like the thing to write on that application. It was picked remarkably quickly and for no good reason.

Ahead of this conversation, I was reading about your work and I have some sense of how I might summarize it, but I’m wondering how you frame what you’re doing in the world.

The Glia Project is first and foremost a project about independence. That can be confusing to some people who aren’t familiar with the project because they look at it and they think it’s about technology. They think it’s just about 3D-printing medical devices for Gaza.

I’m Palestinian. But I’ve been so indoctrinated with white privilege from living in Canada that when I first started going back my thinking was, “I have this great Canadian education and I’m going to teach them how to be good doctors and then everything will be fine.”

When I went, however, I realized that the problem is actually multi-partite. There is a lack of training, but there’s also a lack of access to medical devices. When I would train my residents in Gaza, they would say, “Great training, but we don’t have access to any of this stuff.”

At the time, Egypt was a little bit open. So we started bringing things in through Egypt. I don’t know how familiar you are with the Egyptian tunnels, but there were 1,800 tunnels between Egypt and Gaza at one point. All subject to the whims of the Egyptians. The Egyptians were junior partners in the blockade of Gaza by the Israelis, so we in turn were also subject to the whims of the Israelis.

The problem in Gaza is not a problem of the place being poor or the people being stupid. The problem is that, quite literally, the Israelis stop us from receiving equipment, from getting training, from doing anything. When I looked around, I realized that what we actually needed wasn’t medical devices. It was independence.

I’m guessing you’re in the United States?

Yes.

Americans are the most hopeless people on the Israel-Palestine conflict. They’re like, “Oh my God, the occupation has been there for seven million years and it’s going to be there for seven million thousand more years.”

No. It’s not. It’s collapsing. What’s really difficult to understand until you spend some time there is that it’s obvious that the occupation’s days are numbered. The occupation is collapsing right now, so if we were to run a project that was aimed solely at disaster relief — which is what some people think we should be running — then what would we do after the disaster of occupation is over and we’re left with the other disaster: capitalism?

Now I’m sounding like I’m fucking crazy, but hear me out. When I first started going to Gaza, I thought that I was going to see a place abandoned by capitalism. Then I got there and guess what? KFC was delivering chicken through the tunnels for free. I mean, you had to pay for the chicken, but the delivery was free. Why? I couldn’t understand it. It’s soggy by the time it arrives. It’s like KFC at the bus station. I’m a KFC addict and, like any KFC addict, I recognize that stuff is shit and it’s shit when it’s fresh. Four hours in, it’s really shit.

So why is KFC doing that? Why are they subsidizing free delivery? I also saw billboards everywhere for Coca-Cola and Pepsi, which weren’t readily available at the time. There were also billboards for products that people could never afford, like a BMW or a Mercedes. And they weren’t just in rich districts — they were everywhere.

That’s when I realized, “Oh shit, these guys understand that this thing is almost over too.” Coca-Cola opened a bottling plant there in 2016 that uses more water than all of Gaza has available to it each day. What are they thinking? They’re thinking there’s going to be a day when people can buy Coca-Cola. They’re thinking, “We want to be there first.”

How does that translate into medicine? The moment that medical companies think they can get in there, they’re there. But what if we had the ability to create the alternative before the bad guys show up? The guys who love patents, the guys who love copyright, the guys who love all that shit. What if we could create a culture that was resilient enough that it could resist the coming influx of capitalism?

That was one of the big drivers for the project. I mean, I am actually trying to solve a specific problem — the problem of access to medical devices — but my problem could be answered in a million ways. I could go to the United Nations and ask them to buy some shit and import it. Why aren’t we doing that? It’s because we want to play three-dimensional chess. We want to do something that’s good for today and good for tomorrow.

Are people on board with that? Inoculating Gaza to capitalism by building up the culture around open source and open access? Or do they get on board because you’re a Canadian doctor?

Palestine, like most post-colonial places — let’s call it post-colonial although it’s more complicated than that because it’s still actively being colonized — has an inferiority complex. And we use this inferiority complex against them.

Your doctor’s stethoscope at the doctor’s office costs $200. People see these and associate them with quality because they’ve been around for so long and they’re shiny. And then we show up in Gaza with a 3D-printed stethoscope. It’s plastic. Usually, it’s one color. The first thing they say to me is, “That’s shit. Just look at it. It looks fucking homemade.” I say to them, “Oh really? Because we use it in Canada in the emergency department.” And they’re like, “Gimme that.”

So we’ve leveraged people’s inferiority complex against them. We also flip the development model. The development model, traditionally, is that you go into the Third World, you test on poor people who are defenseless against you, and then you go to the First World to sell your product there.

What we are doing is exactly the inverse. We’re doing all of our development in the First World, and then deploying it in the Third World — the idea being that mistakes are very expensive in the Third World and very cheap in Canada. For example, right now we’re doing a study for a 3D-printed pulse oximeter. That’s the device that goes on your finger and says how much oxygen you have. To test it — even in 2019, if you can believe it — you actually have to suffocate people. You literally put a mask on them and you bring their oxygen down to 70% while you’re draining off blood to test it. If something were to happen, we’re in Canada. I can give these patients the best care in the world. If I were testing it in Gaza and something were to happen, it would be bad news.

The only device we haven’t done that with is the 3D-printed tourniquet. That’s because it was an emergency situation and we needed to deploy them before we could test them. We were testing them on people who were dying. It was awful and totally the wrong way to do it.

What happened?

Any engineer who is not in the field has no idea what the fuck is going on. Paramedics in Gaza were telling me, “These tourniquets are breaking.” And I was like, “Why, what are you doing wrong?”

Then I went to the field. Two tourniquets in a row broke in my hands. I did not have the humility to understand the problem until it was happening to me. What was the mistake we were making? We were testing the tourniquets on people sitting in chairs in Canada. Super calm, super chill. Usually, they were even tourniqueting themselves.

In the field, I was literally running while applying a tourniquet. We had four stretcher bearers and I’d be in the middle, on the right side or the left side of the patient, trying to apply a tourniquet. While we were getting tear-gassed, so I couldn’t see. While there was live fire, so we were getting struck by shrapnel and running for our lives. So, yeah, I applied the tourniquet too tight and it snapped. You’re telling me to twist the tourniquet three times, but not four or it will break? Forget it.

After that, I went back to the engineering team and said, “Okay, we really need to over-engineer this tourniquet and make it something that can withstand 1600% of the force that we expected.” The engineers said, “This is stupid. Why are we doing this?” Because I was there, I knew that the amount of adrenaline pumping through you forbids you from making sound decisions in that exact moment. And since we had that intervention, we have had zero failures in 500 deployments. The commercial brand fails 20 percent of the time. We’re not just equivalent: our tourniquet is better than anything out there on the battlefield.

Innovating Outside the Market

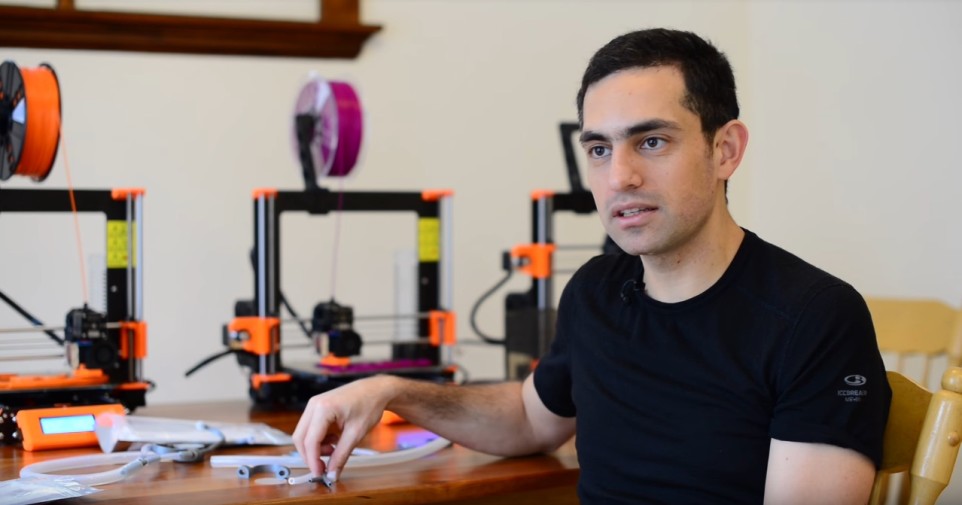

Tell us more about your development process. How do you develop and produce these 3D-printed devices?

We create the designs using FreeCAD, a free/open source CAD software program. And we have medical students doing the production in my basement in London, Ontario. It’s Health Canada-approved. [Ed.: Health Canada is the Canadian public health department and the equivalent of the FDA’s medical licensing division.]

Your basement is Health Canada-approved?

Yeah, they did a site visit this week.

There are six 3D printers down there and a few tables where we quality-check and package each stethoscope. A full print job produces enough parts to make four stethoscopes and that takes fifteen hours. In other words, every fifteen hours, we get four stethoscopes.

The 3D printed parts are the chestpiece, which is circular and holds something called a diaphragm, which is what we put to the patient’s chest; a “y-piece,” which is connected to the chestpiece by some tubing and lets us create a fork; two ear tubes, one for each prong of the y-piece so that sound can flow to both of the wearer’s ears; and finally a piece called a spring, which supports the ear tubes and keeps them a constant distance apart. We put earbuds on the ends of the ear tubes, but we don’t print those.

For the tubing, we use huge rolls of Coca-Cola fountain machine tubing, actually, and cut them up into the size we need. We’re able to leverage the fact that the FDA approves this kind of tubing for both food and medical devices — the “F” and the “D.” We buy food-safe material and then can get approval to use it for medical stuff.

Finally, our diaphragms — inserts for the chestpiece I described earlier — come from file folders, which are super cheap.

You cut circles out of file folders to make the diaphragms?

Yeah, we use a craft punch. We wanted to make it very simple. What’s the good of a process if you need a $2 million lab to implement it? My entire lab can be put together for about $5,000. And half of my machines I made myself. It works not just on the best equipment you can buy, but on anything you can scrounge together.

Once the pieces have been quality-checked, we put them in plastic packets and seal them. They arrive disassembled. The reason we do that is because we want to change people’s relationship with their equipment.

Speaking of quality-checking and making sure everything works, I know that you published a paper in an open-access medical journal where you describe how you validated the 3D-printed stethoscope against the traditional stethoscope.

We looked around and discovered that there isn’t broad agreement on how you test a stethoscope because nobody really cares. We picked a method that uses a “chest phantom,” which is a simulation of a chest that’s a polyurethane balloon filled with two liters of water.

You put sound in on one side and you collect it on the other side, with the understanding that there are a lot of reverberations in there that happen along the way. And then you compare the two stethoscopes to see how the sound is attenuated by the stethoscope. The stethoscope will take away some of the sound, but you want to make sure it’s not taking away sound in important places.

So you record two audio files: one of the sound that travels through the traditional stethoscope, and one of the sound that travels through the 3D-printed stethoscope?

Exactly. And then you run both files through a spectrum analyzer to see how they stack up. The spectrum analyzer we used was Audacity, which is open source.

We used a Hello Kitty balloon, so colloquially we call it the Hello Kitty Protocol, but we couldn’t write that in a publication — we made it sound more scientific. The cost of new materials for the validation study is about $15, and then you also need the traditional stethoscope to validate against. You could say that’s a capital cost. You also need headphones with a microphone in them. And, of course, you need a Hello Kitty balloon filled with water.

Beyond stethoscopes, what are the other kinds of devices you’re developing?

Our big project that I’m really looking forward to is dialysis. Dialysis is also an interesting problem of capitalism. A good analogy is disposable razors. Broadly, in Canada, there’s Schick and there’s Gillette. You can’t use a Schick razor on a Gillette handle and vice versa. That’s called vendor lock-in.

Fundamentally, dialysis machines are a pump, a controller, a flow meter, and a little bit of tubing. Nothing special. The only way for companies to make them profitable is to create vendor lock-in and collude with each other. In California, there was a ballot initiative [Ed.: Proposition 8] to figure out a way to reduce the costs of dialysis treatment. Fresenius and DaVita, the two biggest companies in dialysis, spent $111 million to stop the proposition and they got it killed. That’s good for them because they don’t want competition, and they don’t want price controls. That’s not how they make money.

In Gaza, this creates a problem. Let’s say white people in the United States under Obama decide they want to donate to Gaza, which happened. They donate a bunch of dialysis machines and what are called “disposables.” Machines are about $35,000 a piece. A disposable is a filter plus a circuit of tubing that hooks into the patient to connect them to the machine. Together, the machine and the disposable do the work that a functioning kidney would do: they filter the patient’s blood. Each disposable is about $100 and should only be used once per session. It’s supposed to get thrown away.

But in Gaza, patients take disposables home and wash them and bring them back the next time until they totally disintegrate — which is bad, bad news. It’s circulating your internal stuff. It should be sterile.

Now let’s say that Trump is in office and the Americans have lost interest, but the French have decided that they like Palestine. So the French donate a bunch of disposables that don’t work with the American machines. We put away the American machines, retrain our nurses on French machines, and start using French disposables. It’s the same thing with the Spanish, the Russians, whoever.

We have rooms of machines with no disposables, and rooms of disposables with no machines. Fucking crazy. So patients aren’t getting enough dialysis because we don’t have enough machines or disposables that work together. It’s like if a car manufacturer said you’re not allowed to use anything but Goodyear tires. The tire is the disposable, the car is the machine. This is what the companies are doing to us. They’re making it impossible for us to use anyone else’s disposables.

How can 3D printing help?

Our idea is to make a machine that’s generic, where we can create templates for each of the different companies’ disposables. The template would become an interface between our machine and the proprietary disposable, so that different disposables become compatible with our machine. It would consist of printed parts at every place where the disposable touches the machine, a sheet or a board with a cutout to hold each of those 3D-printed parts, and instructions for putting the disposable, template, and machine together.

The machine that we’re developing, instead of costing $35,000, costs about $500 to make. But each brand new tooling of a template will cost about $15,000. In that situation, if a country wanted to donate, we’d say, “No, no, don’t give us any machines, just give us your disposables.” Even if we have to spend $15,000 each time a new company decides they’re going to give us their disposables, we’re still way ahead financially. Plus, we don’t have to retrain our nurses each time, which leads to mistakes and errors.

So you have to create a new template for each country’s disposables.

What’s tragic about it is that it’s not even one template per country. The United States has two main dialysis machine manufacturers and their stuff doesn’t work with each other. You can’t take a Fresenius disposable and put it on a non-Fresenius machine. It’s the same in Spain, France, and Germany. I wish it were one per country because that would reduce our problem set.

This is why we’re open-sourcing the templates. We’ll open source the whole process, really — the files to 3D-print parts and lasercut the board they plug into, as well as any validation studies we do, and any data we use in those validation studies so people can quality-check their own work. That way, you only have to spend the $15,000 to develop each template once. Let’s say the Americans donate one set of machines to Gaza and the French donate one set of machines to Kenya. We spend our money to make our template and they spend their money to make their template. Then, later on, if the French donate their machines to Gaza and the Americans donate their machines to Kenya, everybody is all set. Because the Kenyans would already have our template for the American machines and we would already have their template for the French machines. A shared open source repository makes it possible for us to not duplicate each other’s work.

What you are describing — bringing technological innovation to a product to make it better and cheaper and more widely available — is what we’re told capitalism already does well. But in your experience, the reality is the opposite. The market is making the product worse. So you’re forced to innovate outside of the market.

The idea behind patents in a capitalist medical model is that, at a certain point, either the benevolence of these companies or their competitive nature should cause them to reduce their prices and make generic versions of their products. Maybe the first version of a particular medical device belongs to a company and you pay an exorbitant amount for it. But then it becomes cheaper and more accessible to everybody.

That promise isn’t being fulfilled in the realm of medical hardware. It is being fulfilled in generic medicines, although the United States has even found a way to fuck that up, which is amazing. Almost no country has allowed drug companies to fuck up generics the same way the US has, where very simple 200-year-old generics cost $20,000. In Canada and in Europe, that shit is just not allowed.

What is a patent? A patent is the government incentivizing innovation by encouraging inventors. It does this by spending people’s freedom — it gives the inventor the right to prevent other people from making or using that invention for a period of time.

Similarly, the government spends people’s money to make a highway. You want the government to make highways. But if the government is spending $20 billion per kilometer of highway, you might say, “Wait a second. I want you to spend some, but not too much.” When highways cost too much — when one kilometer costs $17 million to develop — it’s almost always associated with mafias and corruption. To bring it back to patents, how can there be a kilometer of innovation that costs all of people’s freedom to develop? There must be corruption involved.

What people like myself can do is to force that realization by operating outside of the usual system. A 200-year-old medical device like the stethoscope should not cost $200.

Blockade Runners

Let’s talk about how your medical devices are printed on the ground in Gaza. 3D printers use plastic to create objects. Where do you get the plastic?

It’s recycled ABS plastic. Gaza actually has a 100 percent recycle rate because no plastic is allowed in.

Really?

Yeah, almost everybody’s plumbing in Gaza is made out of recycled plastic. It’s really quite wild. For the printers, we use recycled ABS and we mix in as much virgin plastic as we can get because you always need some virgin plastic — there’s no such thing as 100 percent recycled plastic — but sometimes it’s not very much.

Where do you get the ABS from? I’m imagining a bunch of plastic bottles.

You’re halfway there. Plastic bottles are made out of a material called PET. We don’t use PET; we use ABS, which is the plastic that’s in Lego pieces. It’s also in chairs and tables, picnic tables, shit like that. What happens is: you take those plastic parts, you grind them down, you wash them and dry them. Then you melt them and extrude them into spools of “filament,” which is what 3D printers use to make things.

To process all the recycled plastic in Gaza, they’ve made their own recycling machines, their own grinders, and their own cleaners.

Are those machines open source? Are the plans online somewhere?

Yeah, man. One of them is called the Filastruder. It takes plastic pellets and turns them into spools of filament. The company that makes it open sourced their stuff — and that’s a prerequisite for everything of ours, since we have a 100 percent free/open source stack.

Why are we religiously free software? I don’t know if you’re religiously free software, but zealotry is painful. It sometimes takes us five times as long to do anything, but that cost is paid up front and we’re then able to pass what we learn on to other people and get them on board. FreeCAD, the software I mentioned earlier that we use to design the stethoscope parts, has improved dramatically since we started using it. We’ve filed bug reports against it.

Anyway, we got a Filastruder into Gaza and started doing some amazing shit. And we began ordering parts from the company in a really weird way. One day they emailed me and said, “We’ve never seen anyone order parts the way that you’re ordering them. What are you doing?” So we explained what we were doing and they were blown away. They sent me lots of replacement parts for free, which was kind of them.

We’ve since had to go more industrial: the Filastruder was good at the beginning, but now we’ve got twenty printers in Gaza and we’re producing many kilograms of filament each week, so we can’t use it anymore. But it will always be in our hearts.

Are those twenty printers all in one place, or spread around?

They’re in our offices in Gaza. But we help make printers for anybody who wants them, by printing the parts that they can then assemble into a functioning printer.

There are two reasons we do this. One is that we want to promote the culture. The other is that we’re going to get bombed at some point. When that happens, if we are the only place that has all the 3D-printing knowledge or equipment, then we’re going to set back the entire movement by two or three years. The more we hoard the knowledge or hoard the equipment, the worse it will be. As it is, when our offices eventually do get bombed, we’ll probably only be set back a year. If somebody dies, obviously it will be even worse.

So while we have twenty printers of our own, we’ve “birthed” approximately thirty-five more by printing parts for them. It’s easier for people to get up and running if we give them some parts to start, kind of like a sourdough starter. But what’s really cool is that printers have started showing up that we had nothing to do with.

How did you know? How could you tell that these weren’t printers you had helped make?

Historically, everybody had what’s called the Prusa printers, so it was always easy to trace them. At this point, there are Prusa printers that are second and third-generation. We’d make a printer for somebody and then they’d make a printer for somebody. The first thing we ask people to do is print themselves backup pieces, and the second thing we ask is for them to help somebody else.

Still, it’s a monoculture. Monocultures, even when they’re open source monocultures, are not good. So when we finally started to see printers that weren’t ours, we knew they weren’t ours. The culture is growing in a way we didn’t expect.

We’ve started working with universities and high schools. The goal is to get a 3D printer into every high school in Gaza within the next five to ten years. For us to have as many 3D printers as they have in the Netherlands per capita would mean having around two thousand printers. And Gaza needs more printers than the Netherlands because they’re making essential stuff. For example, if your light switch breaks in the Netherlands, it’s usually cheaper and easier to go buy it at the hardware store. In Gaza, these breakages are permanent. When you go to somebody’s house and the light switch is broken, it’s always going to be broken. Introducing 3D printing to that culture is empowering repair culture.

What about the cost and the availability of electricity? Does that create an obstacle for 3D printing in Gaza?

Our office in Gaza is solar-powered. We knew right away that the electricity instability in Gaza would kill us if we wanted to print consistently, so early on we rigged solar power for the entire place. We have panels that power the equipment during the day and charge a set of batteries, which we can then use for backup. I’ve also participated in several multimillion dollar projects to put solar power in hospitals in Gaza. Those are important, because if you’re trying to help a patient and then the electricity cuts out for eight hours, it’s not good.

Does democratizing access to basic goods, leveraging solar power, and creating self-sufficiency pose a threat to the Israelis and the occupation? Since their withholding of those things is a large part of how they maintain control?

There are three main components to building a solar power system in Gaza. The first is batteries. In a country like Canada, you wouldn’t have to bother with batteries because you can always access electricity through a reliable, always-on grid if the sun isn’t shining. But in Gaza, batteries are essential. The other components are the solar panels and an inverter, which translates the different kinds of current into each other — so the photovoltaic power generated by the panels, which is DC, can be converted into the kind of power that our building uses, which is AC.

There is no moment in time since I started my work that the Israelis have allowed all three of those components into Gaza at the same time. It’s always one and the others are banned.

It’s clear that the intent of the blockade is to take away independence. So maybe the logic behind the Israelis preventing those components from entering Gaza is part of that. Honestly, I don’t think about it that much. What I care about is building a project that’s sustainable and that’s decentralized. Decentralization is deeply Palestinian. The context is partly religious: Islam is a decentralized religion. But Palestinians have not had good centralized leadership for a very long time. Historically, they organized themselves into villages that were more or less independent. So we’re not introducing new concepts to people. What we’re doing is simply refreshing what they think their community should be, in a technological way.

Lucky and Grateful

Have you always been interested in 3D printing? Or did your experiences in Gaza spark your interest? In other words, were you thinking about the problems in Gaza and matching 3D printers to the problem?

A little bit of both. I understood that the technology might be usable, but as long as the tunnels were open, it didn’t make sense. I was meeting my needs in other ways, so why bother?

Now, it’s just too expensive. If I were to distribute a stethoscope to each doctor in Gaza — that’s 4,000 doctors — that would be $200 per stethoscope, but probably more like $350 by the time you got them into Gaza because of the corruption, the problems with the Israelis, and so on. You’re talking about $350 times 4,000 people. That’s really serious cash. And for what? For stethoscopes. Whereas 4,000 3D-printed stethoscopes — even with packaging, distribution, training, and everything — are $5 a pop. For $20,000, you can kickstart an entire medical system. That’s nothing.

Now that you’ve kickstarted that medical system, why keep going? At this point, the office in Gaza has the designs and the printers. Why have you continued to show up in person?

There are a couple of reasons for that and they all have to do with benefits to myself. It’s common for people who travel and volunteer to imagine that they are giving and to minimize the amount they’re taking from the society they’re in. The reality is that without absorbing the resilience of the Palestinians, I would have never understood what resilience was. And so I took hope from them. I took from them the idea that when somebody builds a wall, you dig a tunnel.

That recharge of my energy is hard to do when I’m not there. I’m not the kind of person who can easily empathize with a situation without seeing it. I’m also not smart enough to be able to read what’s happening in the news and tease out the reality on the ground. Had I not been there in the first place, I wouldn’t have understood these problems. Someone might understand that there’s a shortage of medical equipment, but it’s hard to understand how that shortage is actualized. What does it look like? Going there, I take a lot that helps me to do the work here, which makes me a better doctor both for my Canadian patients and for my Palestinian patients. That’s the main reason.

But above all, Gaza is a vanguard. It allows us to acid-test our ideas about freedom, about non-violent resistance, about healthcare provision, and about independence.

In May 2018, you were shot in the legs by Israeli soldiers in Gaza and Canadian prime minister Justin Trudeau called for an investigation into your shooting since you were clearly marked as a medical personnel, and shooting marked medical personnel is a war crime under the Geneva Convention. You responded that you weren’t interested in an investigation and that you’d rather have investment in infrastructure projects. I’m wondering if you can talk about why.

There is no possibility of justice through the Israeli system as it currently exists. Things like investigations are fig leaves to pretend there is justice. Ultimately, whether there’s justice for me or not is irrelevant. What I want most is to improve the conditions I saw around me that triggered people, week after week, to go to the protest. [Ed:. The protest is the Great March of Return, which began March 30, 2018.] It’ll be fifty-two weeks on March 30, 2019. 20,000 people shot. 250 deaths. More by the time you publish this. Why are people going? It’s because they are desperate. If we can alleviate the desperation, that’s the key.

Whether Tarek Loubani gets justice is irrelevant in the grand scheme of things. If we could get a couple million dollars to put solar panels on some hospitals, that would be a legacy I would be proud of. What’s the best case scenario if there’s an investigation? The absolute best case scenario is some fucking nineteen-year-old getting thrown in jail for a year for what he did to me. So they would destroy some nineteen-year-old’s life even though we all know it’s a systemic problem? No thank you. I would rather make it so that that nineteen-year-old is never in the position where his whole life depends on him shooting a doctor. I would rather make it so that Palestinians don’t have to go up to the fence with their hands up begging for their humanity.

I’ve never seen an honest figure or independent judicial process from the Israeli government. In fact, the Israelis came to interrogate me. They sent people in army uniforms calling themselves an “independent fact-finding mission.” I joked to one of the guys, “Having the word 'independent' doesn’t make you independent. You are a literal soldier.” He said, “Yes, but we take this very seriously.”

You work in and on bodies. What’s your relationship to your own body? And does it change when you’re in Canada versus Gaza?

My main relationship to my body is gratitude. I felt incredibly lucky when I was shot that I wasn’t hurt more severely. I could see how important everything that we were working towards was. We are — collectively, not me specifically or even the Glia Project — trying to make it so that these fragile vessels we all inhabit are as well-cared for as possible in a way that’s just and equitable across the world. There is no reason why patients in Gaza shouldn’t enjoy the same medical care that my patients in Canada enjoy. There’s no good reason for that.

A lot of people look at the fragility of their own body and they’re terrified by it. But those same people look at a glass sculpture and aren’t terrified by its fragility. You can look at fragility as a kind of beauty and as an invitation to protect. I take up that invitation. I take it up professionally and I take it up in this work. But your question is philosophical and I’m not a philosophical person so it’s hard to answer.

The other part, in addition to gratitude, is luck. The guy that rescued me the day I was shot was killed about an hour later.

Musa, right?

Musa. He was a father of four. His wife, when she talked to me, asked, “Why did he die and not you?” Good fucking question. It’s part of that fragility. Have you ever dropped a glass that didn’t break and wonder, “Why didn’t it break?” And another time, it just taps the side of the sink and shatters into a thousand pieces. Why did it break?

Musa died because of a totally preventable condition. Well, treatable, not preventable. I guess it was preventable because they could have not shot him, but I could have treated it with a ballpoint pen. And the wild thing is: my mind can’t look further than my people. I can only think of the paramedics who were shot that day. I can’t even begin to fathom the 1,700 other people who were shot that day. I don’t know how big your high school was, but my entire high school was 1,700 people. It’s like every one of them being shot in one day. So I felt lucky. Lucky and grateful.