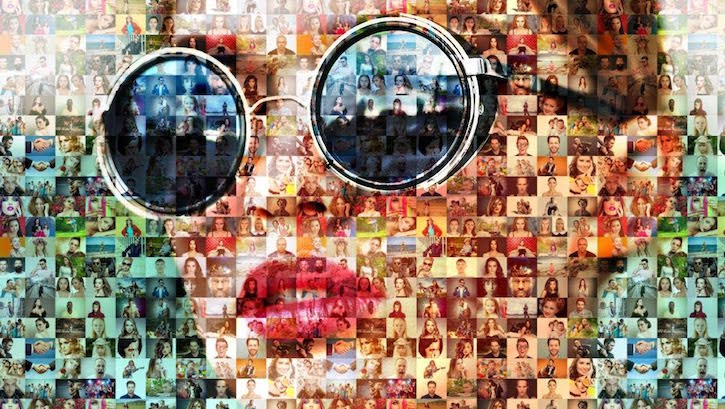

Supposing the internet was a woman—what then?

This is not exactly how Friedrich Nietzsche began his book Beyond Good and Evil, when he first published that book in 1886. But it is one of the questions I have been thinking about ever since I first saw “#MeToo” in the Facebook status of a colleague one night last October.

I was at a bar with my husband, and a couple of men we had just met. I knew immediately what the hashtag meant, even though I had only ever met the colleague who posted it a few times.

“#MeToo,” I typed with my thumbs, under the table.

A minute later, I slipped my phone back out of my handbag and deleted the post.

I am not sure what I felt afraid of. When Nietzsche asked what if Truth were a woman he meant: Was there any such thing? Nietzsche believed there was not such a thing; or, rather, that the kind of Truth philosophers had been talking about all these centuries would never reveal itself to them. At the key moment, Truth would always draw back. Truth was a cocktease, teasing philosophy, which was a man. The philosophers should give up already.

(The love life of Friedrich Nietzsche seems to have been unhappy.)

It might sound strange to say the internet is a woman, when you meet so many misogynist men online—so many of whom love Nietzsche! Or, at least, what they see about him on YouTube or read about him on Reddit. But when I ask if the internet is a woman I am not only thinking of all the women using the internet to talk to one another. I am also thinking of how much of what we do online corresponds to activities that have traditionally been seen as female.

Social media make “women” of us all. We preen and pose, hoping to draw eyes to us. When others do the same, we emote for and affirm them. We share events of everyday life that had never before been considered newsworthy. Here is my baby. Here is my breakfast.

I should make clear that when I say “woman,” I do not mean a person whose body has this or that biology. I am not interested in chromosomes or hormones or genitals—not now. I mean a person who is expected to do certain kinds of work. Namely, the kind that is not seen as work, not really, but rather as expressing “natural” emotions. Childbearing and rearing and household chores are classic examples. But our culture considers care of all kinds feminine. And we treat female feeling as a natural resource that anyone can take for cheap, or free.

Smile, sweetheart! You have such good soft skills.

On online platforms, we make money for other people, in return for the feeling that we are being seen and maybe even loved. In return for a digital place to live, we click. We let the men who own the platforms keep tabs on us 24/7. Good “digital housewives,” as the media theorist Kylie Jarrett has named us, we spend our days making “cookies” for them!

Sexism at Scale

One result of this arrangement is that the internet has become an engine for the accumulation of vast sums of capital. What a good business model, to get countless people to do things that make you money all the time, without paying them to do any of it!

But another effect has been consciousness-raising. Social media shows just how political the personal is. If nothing else, social media platforms are vast machines for revealing structure. Facebook and Twitter encourage each of us to share the details of our lives all day—and then analyze these data points to discover patterns. People who like x also like y. People who look p and q ways are likely to have r happen to them.

Correlation may not be causation. But, as networks encourage us to discover our commonalities, to join a chorus of likes and retweets and hashtags, they show us the systems we live in. This may be why Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube have made fitting homes for both conspiracy theories and new social movements. They remind us that even our most intimate experiences are not only our own; they prompt us to classify and tag our thoughts in ways that link them with those of others.

You may have spent years wondering: What if I had just said something else? Why did I have to have that last drink? Wear that dress to the interview? The internet will tell you: Maybe. But, look, the Thing that happened, happened to all these other people, too.

Once you see structure, you cannot unsee it. The duck becomes a rabbit. The vase becomes two faces, staring each other down. The question is: What next?

The morning after drinks with my husband and the other men, I arrived at my office and opened Facebook to kill time: A solid wall of #MeToos. I typed my post again. By then, it did not feel scary to do so. Or if it did, it was only because the statement felt too obvious to bother making. (My “#MeToo” got only fifty-six reactions.) Smart friends were already adding qualifiers. “#MeToo, duh.” “#MeToo, obviously, but also, I want to live in a world where women do not have to choose between identifying with men and seeing themselves as victims.”

In the months since, the news has sped by like the third act of a horror movie. Like the mom who thought she was going crazy (cue: furious paging through old books and shuffling of Scrabble tiles), woman after woman is making her audience see what she is finally sure she sees. There really is a ghost! The clue was right there in the carpet where we had been standing!

We are seeing sexism at scale, in other words. If there is fear in the elation of our anger, that fear, and not a little sadness, comes from the Bad Guys being our fathers, husbands, boyfriends, brothers, sons. You’ve always been the caretaker. In heterosexuality, the call is always coming from inside the house.

Good Neighbors

The standard reading has been that the sad and ugly stories that appear under the hashtag #MeToo constitute a “revelation.” I am not entirely convinced. I know, we must leave room for the problem of other minds. “Assume good intentions,” as they say. It has been a long season of peering over the fence and feeling stunned by everything you do not see in the yard next door. And yet you want to stay good neighbors.

I meet a Good Man—or a friend I think is one, anyway—for lunch and he cannot believe the thing he read about our other friend—a story that all of the female friends we have in common knew. We are trying to decide what we should do about it.

My husband and I meet a Good Man and his wife for dinner, and the Good Man starts telling a story about another Man who did x to his subordinate, years ago, and how the Man was talking about it the last time they got drinks together until I feel like I cannot not interrupt: “Did you not know that that subordinate was me?” My friend feels terrible for bringing it up. I feel relieved that he really had not known. It was not what I ever wanted to be known for. Still, as I smile it’s ok, I feel like my face is on too tight. My heart keeps beating all over my body.

“There are reasons you do not come to us with these things,” another Good Man reflects, about women, at a holiday party. He’s right. There are open secrets and then there are the secrets we keep even from ourselves. A senior colleague tells me, out of nowhere, about a dissertation advisor and how he threatened her, decades ago. The other night I went home and wrote it all down. I printed it out and folded it and put in an envelope. The advisor is long dead. I’m not going to send it anywhere. I just had to. A friend tells me about a powerful man asking her whether another powerful man they worked with was touching her, his college intern.

In a different context, a colleague says something I keep thinking about: “You have to allow people their shock.” She is talking about all the white people who, since Trump became president, or since they saw the Eric Garner video or the Philando Castile video, keep saying this is not us, meaning they do not recognize America. She wants to laugh. “Are you kidding?” But she believes it is better, in the long run, not to laugh in the faces of people who want to be allies. She believes this, even as she cannot help but marvel at the luxuries of their ignorance.

I know there are differences among these differences. But I think about it when I think about the shocked men. How hard do we work not to know what we know? When do we decide we have to?

(“We” who?)

Some of the specific details that have come out of #MeToo are shocking. The executive throwing the young reporter down the stairs. The button under the desk that locked the office door, locking you in. But the gist—that men in an unequal world use women to feel powerful, that they abuse their power over women, and often weaponize sex to do so… Who can remember the time before they knew that? The fact that we can be raped is the subtext of so many warnings we receive as girls. Do not wear this. Do not go there. Try your best not to exist, in public.

Clickbait Deathmatch

To get to my provocation: I suspect that what #MeToo is revealing about the behavior of men within the media industry is less new than what it reveals about the industry itself. #MeToo is registering a change that has less to do with what we know than how.

Whatever else it is, #MeToo is great digital content. Nobody does not have a stake. Nobody does not have an opinion. Stories of workplace abuse come with a titillating hint of pornography—particularly in the privileged, mostly white settings that have received the most media attention. We are supposed to be watching some kind of battle of the sexes, and we may be. But more often, these are battles between young women and older women, between Cool Girls and “cry-bully” victims, staged as a clickbait deathmatch.

The shape that #MeToo has taken reflects an ongoing contest between legacy media and digital media—and the way that these different forms of media get gendered. The Major Magazine, run by mostly white men, feels itself being eaten alive by a feminized (meaning: unpaid or underpaid) digital media ecosystem. There, women and queer people and people of color and working-class people have louder voices than they used to. But very few writers make a living.

The drama that unfolded in January 2018 regarding the so-called Shitty Media Men List and Harper’s Magazine reads like an allegory of the struggle between masculinized legacy media and their feminized digital rivals. A recap of the chain of events:

-

An anonymous young woman creates a crowd-sourced Google Doc, shared and filled in by other anonymous women, and takes it down after less than twelve hours.

-

A legacy magazine run by an old man with inherited wealth, Harper’s, reveals that they plan to identify the creator of the Google Doc in an upcoming cover story by Katie Roiphe, a pundit who established her career by dismissing the existence of date rape in the New York Times, back in the 1990s.

-

Dayna Tortorici, the young female editor who took over n+1, a literary magazine founded by four to five men, tweets that the “legacy magazine” responsible for the story should not out the Shitty Media Men list creator.

-

Nicole Cliffe, a writer and editor best known as the founder of the (now defunct) feminist website The Toast, retweets Tortorici, and offers to compensate any writer who pulls a piece from Harper’s. The campaign gathers momentum on Twitter.

-

The creator of the spreadsheet, Moira Donegan, preempts Harper’s by publishing a long essay outing herself in New York magazine’s digital native “fashion and beauty” (women’s) vertical, The Cut.

-

The internet lights up. Donegan gains tens of thousand of Twitter followers overnight.

-

Weeks later, on Super Bowl Sunday, Harper’s publishes its anti #MeToo story online. The subhead announces that “Twitter feminism is bad for women.” www.harpers.org gets more clicks than it has had in ages. Over the next few weeks, Harper’s sees a modest bump in subscriptions.

The process repeated itself the week after news of the Harper’s cover story leaked. On January 14, the online magazine Babe.net published an anonymized account of a bad date with the actor Aziz Ansari. Suddenly, a low-paid woman’s words (and screenshots of her text messages) went viral—and pundits at The Atlantic and The New York Times rushed to get a piece of the traffic by denouncing a feminist website that, until then, few of their readers had ever heard of.

Crazy Girlfriends and Straw Women

The Media Men List showed what online platforms let women do: shareability means scalability, even if nobody is getting paid. Nobody but Google, that is. The internet made the whisper network clearly legible—and portable. But who was going to monetize it?

Harper’s is the oldest general-interest magazine in the country. It is also one of the most notorious for failing to publish and promote women. And it is almost certainly the very worst at the internet. The website interface is risible. At the time of this writing, they have paywalled the Katie Roiphe article again.

Harper’s clearly craved online traffic. And they concluded that discussing a Google Doc written by anonymous women could be a great way to draw it. When their intention to reveal the name of Moira Donegan leaked, women on Twitter protested. On NPR, Katie Roiphe compared them to “a mob with torches outside the window.”

There goes Twitter, like a girlfriend, being “crazy”!

So Moira Donegan did the only thing she could do, which was to scoop Harper’s by telling her own story in a women’s vertical.

The Internet of Women: 1, Major Male Media: 0.

When the Harper’s article finally came out, its six thousand rambling words said little that many others had not said already. Amid a lot of posturing falsely suggesting that others denied this, the piece advanced the following, indisputably true argument: Addressing the systemic, gendered inequality that pervades American workplaces—inequality that both expresses and maintains itself through the sexualized abuse of power—will be… complicated!

The author, who teaches writing at New York University, seems to have missed the memo that says theories should be falsifiable. In order to create rhetorical drama, she had to suggest that there were people out there online saying that the situation was not complicated. Ironically, the main evidence that she cited of such refusal of nuance—indeed, the only named sources in her entire piece—came from blog posts and tweets.

One technique that Roiphe used in Harper’s is the signature of many anti-#MeToo op-eds that have appeared in other legacy publications. I call it The Straw Girl. This technique posits the existence of a hypothetical observer who is conflating things that should not be conflated. It discredits the testimony of real women by implying that other, imaginary, women are too stupid to know the difference between getting raped and having a guy be “creepy in the DMs.”

Let us set aside the irony that the very pundits who accuse the Straw Girls of confounding things seem to think that having people in your office gossip about you is tantamount to getting fired and jailed. It does not seem unreasonable to ask whether these acts of sexualized aggression exist on a spectrum. I have never heard any woman say that the harms they cause are the same.

But Roiphe used another, newer, strategy in concert with the Straw Woman: feigned naivete. She quoted young women who were clearly making jokes online—tweets like “It’s not a revolution until we get the men to stop pitching LMAO” and “Small, practical step to limit sex harassment: have obamacare cover castration”—but refused to recognize these jokes as jokes, or personae as personae. Roiphe may have looked like a digital Rip van Winkle. But her incomprehension was a power move.

I don’t know how Twitter works, this move said, and I’m proud not to. I write for print! In contrast to the authors of the anonymous Google Doc she criticized, Roiphe probably got paid at least a few thousand dollars for her thoughts.

Taken as a whole, the Harper’s cover story constituted an attempt to assert control over discourse in the digital public sphere—a sphere that merges the public and private to the point where those terms may no longer make sense. In much the same way, New York Times editorialists Bret Stephens and Bari Weiss rail against “Twitter mobs.” Despite the fact that, as one recent leak showed, they have plenty of critics among their coworkers in the New York Times office Slack. If these critics hesitate to reveal themselves, it’s because they fear getting dumped from their jobs—back on Twitter, among all the other Crazy Exes.

Season of the Witch Hunt

One way that critics dismissed the “Twitter feminists” arrayed against Roiphe was that these women were leading a “witch hunt.” For some time, witch hunts have been in the air.

Donald Trump regularly complains that the ongoing Russia investigations constitute a “witch hunt.” In the wake of a series of scandals during the summer of 2017, men in the tech industry were claiming that witch hunts were running wild on the West Coast, too. In early August, after the “gender diversity” memo that got James Damore fired from Google, the entrepreneur Jeff Giesea told The Guardian, “it’s a witch hunt.” In a widely shared story about pushback against the campaign for gender equality in tech, engineer James Altizer told the New York Times there was a cabal of feminist women looking to subjugate men in the industry—”It’s a witch hunt,” he concluded. In the wake of the revelations about Harvey Weinstein’s long history of harassing and assaulting women, Woody Allen warned against “a witch hunt atmosphere.” Most recently, the director Michael Haneke told the Austrian press that #MeToo had created “a witch hunt that should be left in the Middle Ages.”

There is an obvious irony to this. When anti-feminists, serial harassers, and rapists say they are victims of “witch hunts,” they are claiming a status that has historically belonged to vulnerable women. And when Trump says that he and his (large adult) sons are the targets of a “witch hunt,” he is deploying a strategy that Republican leaders have used for years: appropriating the language of “identity politics” from historically marginalized and oppressed groups in order to claim victim status. (Cf. “reverse racism,” “white genocide.”)

But the “witch hunt” has a special salience under a Twitter President. The ubiquity of witches demonstrates the slipperiness of political signifiers in the age of social media and memes.

As Jo Livingstone observed in The New Republic in summer 2017, witches were trending for a few years before Donald Trump started talking about them. Through clicks and other consumer choices, many women, queer and straight, adopted the “witch” as a transgressive identity. During the Hillary Clinton campaign accusations of her statecraft-witchcraft flew; Rush Limbaugh memorably called her a “witch with a capital B.” Following her defeat, supporters took up the witch label as a form of defiance. At the Women’s March and other protests in the aftermath of the election, variations on “we are the witches you couldn’t burn” became popular slogans. Lindy West delightfully flipped the paradigm in her New York Times op-ed, “Yes, This is a Witch Hunt. I’m a Witch and I’m Hunting You.”

What we see in these repeated appropriations, reappropriations, and resignifications is that “witch” and “witch hunt” can mean almost anything. The context is no context. That is, the context is the internet.

Witches of the World, Unite!

Revenants, by definition, return. In America, the language of witch hunts tends to reappear during moments of struggle over cultural authority: during the McCarthy era’s persecution of alleged Communists, and during the “culture wars” of the 1980s and 1990s. Now, the web is stoking new fears about how information spreads. Enabling content by even relatively marginalized people to scale rapidly and unpredictably, it makes all information potentially contagious. #MeToo gained momentum because billions of “digital housewives” are clustered on the few big platforms that now comprise our “global village.” Concentration makes the spread of information uncontainable.

But it is striking that, even as we recognize that sexism and sexual harassment permeate every layer of American life, the men that own the platforms where we are having these conversations have mostly avoided their consequences. Tech has faced relatively little #MeToo reckoning. Susan Fowler and others drew attention to systemic sexism at Uber, and a series of stories in the summer of 2017 brought scrutiny to a few venture capitalists. At least one or two wrote apologetic Medium posts pledging to “do better.” But mostly, the real seat of media power—Silicon Valley—has been spared. So too have the Wall Street firms that help provide the flood of capital lifting the private yachts of West Coast seasteaders.

As legacy media desperately try to snatch clicks with #MeToo content, they continue to hemorrhage eyeballs and money to Big Tech. As they throw young women to the internet as clickbait, the companies that own the internet—companies bigger and more male than any Major Male Magazine will ever be—circle them.

Historically, witch hunts took place at moments of economic transition. Feminist writers such as Barbara Ehrenreich, Deirdre English, and Silvia Federici have shown that the killings of thousands of young women in the early modern period was not primarily motivated by medieval superstition. (If it had been, one imagines there would have been comparably vast and violent witch hunts throughout the Middle Ages; there were not.) Instead, the state persecuted women en masse during the transition from feudalism to capitalism and, again, when men in authority sought to drive women out of traditionally female healing professions.

Witch hunts were crackdowns on women workers, in other words. You can see it in the accusations that witch hunters made. Squint and “black sabbaths,” depicted as feasts and orgies held in the woods at night, come into focus as clandestine workers’ meetings. The acts of “stealing” or “eating” children becomes providing reproductive care. The roots and herbs that became part of the iconography of witchcraft were medicines, abortifacients, contraceptives. As women tried to gain power over the conditions of their labor and their lives, witch hunts aimed to destroy that power—keeping women dependent on patriarchal institutions.

Today, #MeToo marks the site of a struggle for the chance to work with dignity. Sexual harassment serves to keep women precarious, blocking access to capital—literal, social, cultural—and to the networks that distribute it. At the same time, it is the precarity of so much work that makes many women vulnerable to harassment in the first place. If the conversation has moved beyond the workplace to what we might once have called private life, in many industries the porous boundary between work and life is a sign of precarity, too. You never miss a chance to network if you never know how long a job will last.

Writers cannot afford to romanticize the internet we have. It has squeezed the economics of media, and thus the wages and working conditions of everyone in that industry. Yet the internet also provides tools that can be used to build alternatives. In this sense, the internet is ambivalent. Fortunately, inhabiting ambivalence is something that women are good at, having had to practice it for so long.

One thing is clear: When enough people whisper the truths about their lives together, they cast a powerful spell. For months now, we have been living under it. In that murmuration, a question like a heartbeat: What now? What now?